In Their Own Words

Caylin Capra-Thomas on “Lightning Suspected in Death of Horses”

Lightning Suspected in Death of Horses

I want to take you to the black-mud spring pasture

where six horses fell and did not get back up.

I don’t know if they were dark or dappled—

I wasn’t there. I read it in a newspaper in Vermont,

sitting at the counter of a diner that no

longer exists. Lightning Suspected in Deaths of Horses—

small article in a bottom corner, not much

more information than that. It struck me—

I’m not trying to be funny—I carried

that headline around until it became a slogan,

although I’m not sure what I’d been sold.

Maybe this: the sky opens, you kneel

and beg its mercy, and it doesn’t make

one lick of difference. Or maybe, light appears

and your life is transformed. Finally getting

exactly what you asked for all along:

a shift in luck, sudden brilliance, your body

lit, electric, your own enough to let it go.

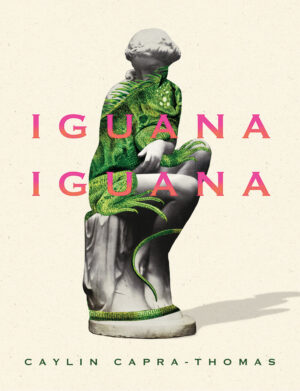

From Iguana Iguana (Deep Vellum, 2022). Copyright © 2022 by Caylin Capra-Thomas. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher.

On “Lightning Suspected in Death of Horses”

“Lightning Suspected in Deaths of Horses” really does borrow its title from a headline, which I remember reading in the Burlington Free Press at the Sadie Katz diner (RIP) in Burlington, Vermont, in 2009. It got stuck in my head, like a song—I was obsessed with the image. These massive, formidable creatures brought down, I imagined, in a flash, all together and all at once. I kept telling my friends about the headline and the story, and they would say something like, “That’s nuts,” and then the conversation would move on, but my mind wouldn’t. The headline’s allure could have been easily summarized as, “Wow, you can really just be hanging out with your horse friends in a nice field one second, and every single one of you can be dead the next.” But I spent years trying to tease out a meaning from what I think was actually a reaction of pure existential dread. That’s poetry for you!

I first wrote a short story with this title. In the story, the protagonist reads the same article I read in the Free Press, and he, too, is struck by it, but I can see in this early attempt to write something on the headline that I was still just trying to figure out the nature of my own investment. The biggest change between the story and the poem besides genre is that the poem acknowledges the impact of the headline’s image but doesn’t spend too much time trying to figure out the reason for the impact itself. In a poem, you can take that kind of thing for granted. Of course, the speaker (me) is obsessed with the idea of six horses being struck by lightning on the same night. Who wouldn’t be?

Accepting the obsession as a given allowed me to think all the way through the image and into a resolution not only for the poem but for the existential dread that bore it. When I stopped asking, why am I obsessed with this particular death? I found, for a moment, an acceptance of and even glory in the body’s impermanence, the once sneaking suspicion turned awful and freeing knowledge that we are all just borrowers of our own flesh, our time on Earth brief and fraught and never exactly what we wanted—until the end, when whatever it was turns out to be all we want, have ever wanted.