In Their Own Words

Danielle Blau on “Penance”

Penance

I offer up

this flowerbox my skull

dear whoever

let its luxuriance

exceed its baseness

let me curl

in the blueblack

root hairs and wait

for you

wind in my teeth

will sough sweetly

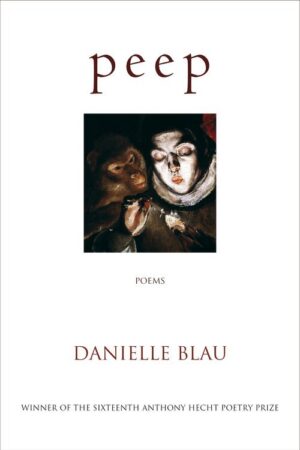

Reprinted from peep (Waywiser Press, 2022) with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

On “Penance”

“Penance” is the oldest poem in my debut full-length collection, peep. It is so old, in fact, I was still a receiver (and not yet a transmitter) of assigned prompts when it came to me unprompted, and I submitted it under the guise of my response that week, I remember, since our prompt had left me cold (and poem-less). “Penance”—fully formed almost—simply arrived, which has always felt like one of the rarest and most holy of events. There was some post-facto tweaking, but for the most part it emerged, from the depths of my inexplicably guilt-wracked psyche, complete and obelisk-like.

Although it arrived directly after my receiving a particular prompt, then, “Penance” was not a response to that prompt, so much as just fortuitously prompt-adjacent enough for me to (almost-) guiltlessly submit it as such.

This was the state of affairs as I plainly saw them at the time.

But looking back at “Penance” now, what startles me most is how much it reads like a plain-as-day enactment of an insight by psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott: “Artists are people driven by the tension between the desire to communicate and the desire to hide.” What more overt expression of the artist’s desire to communicate than “I offer up/ this flowerbox my skull// dear whoever”? Of the artist’s desire to hide than “let me curl// in the blueblack/ root hairs...” (especially given the broody self-lacerating doubts introduced in the two lines directly preceding)? And so it would appear that I had dutifully responded to our prompt that week—which was write an ars poetica!—after all.

But then why had I been so convinced that ars poeticas left me cold? Why had the prospect of writing one felt so embarrassing, almost?

Artist’s desire to hide acting up again?

This seems highly not unlikely. But if so, my artist’s desire to communicate gained the upper hand, it’s clear, since somehow or other I was hoodwinked into writing (there can be no mistaking it) an ars poetica—the poetic form that mortified me, made me want to run screaming, to hide—without the least suspicion that that’s what I was doing.

Oh, and I should mention that my poem is also so old, when it came to me (complete and obelisk-like from the depths of my psyche, etc.) I’d never read or even heard of Donald Winnicott, whose quote about conflicting desires and the artistic drive (upon my first encountering it, many, many years after penning “Penance”) felt shocking to me, monolithic and gem-like, like a revelation. “But poems are like dreams,” writes Adrienne Rich, “in them you put what you don’t know you know.”