In Their Own Words

Fred Schmalz on “Studio Museum”

Studio Museum

One arrives by bus as one

arrives on foot, overshot

two avenues if not off early

trundling eastward in landing gear

touchdown, in rollerskate

suitcase, and one is imminently

hungry. That’s me and my lover

in the doorway recess eating

pizza carried overland in tinfoil.

In the photo of this street, we’d be

whited out, not erased from history

so much as burnt through

onto volcanic rock, our gold

arms and gold fists lead us

to the podium as if we are a bannister.

“I have made no sound,” the sound said.

We eat and are eaten by the scene

before we retire to rooms above

street level, din still audible, at bay.

We are wise to walk back among

presents the past pulled from

a multitude. The fantastic sneak:

dawn’s erosion into full-blown light,

hours from what you call “Young Evening,”

a post-dusk transference, blues’ send off.

But this, this is noon and one arrives

wide open. We woke among livestock,

reaching in time a commonplace humanness,

should we ever need to unwrap it.

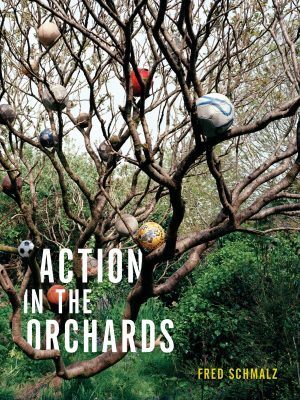

From Action in the Orchards (Nightboat Books, 2019). Reprinted with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

On “Studio Museum”

“Studio Museum” was inspired by a trip I took with Susy Bielak from Chicago to New York in June, 2014. We went straight from LaGuardia to view Glenn Kaino’s sculpture “Bridge” and the exhibition “When the Stars Begin to Fall” at the Studio Museum in Harlem, schlepping luggage and our lunch with us. “Bridge,” an installation of a long undulating series of disembodied gold arms, cast on sprinter Tommie Smith’s gloved-fist salute from the 1968 summer Olympics, swept through the museum’s lower level. The simplicity of this gestural work contrasted with the richness of “When the Stars Begin to Fall,” which included works by both self-taught and established artists examining the American South.

In my writing, I tend to approach artworks as catalysts for connections—between conversation in the gallery, things going on in my head, things I’m reading, things happening beyond the walls of the gallery—rather than as things to be “written about.” On this day, the confluence of images and ideas began in the gallery but really started firing only after we had recollected our luggage and tipped out the door onto 125th Street.

I was attuned to the fact that Susy and I were traveling together that day, which differs from how I travel alone. Traveling together affords a kind of experiential triangulation that acts not so much as confirmation than as an extension of the senses. Often, we point out things the other missed. So, we get both sensory input and running reportage of what lies just beyond each of our own experience. This feels to me like a form of multiplication—experiencing something with someone else affords me another set of senses and additional language to parse it. For example, Susy had been trying to pinpoint the exact moment, late in twilight, when the sky’s color could be considered “Young Evening,” which had become a kind of game for us over the course of that spring. In that way, this is a poem about love and noticing and naming.

I was also cognizant of the entire sensory environment as I was writing, particularly the acoustic dimensions. I am continually fascinated by the ways sound functions in urban settings, and that particular Thursday at lunchtime on 125th St. was bursting with possibilities. Sound piled on sound, from voices and cars and speakers and phones and scraping skateboards and the unidentifiable din and sweep of the city. But it was New York and so there were also instants where it cleared out, dissipated, and gave way to moments when you could hear yourself think. I had been thinking for a few weeks about how to “quote” a sound, and that desire made its way into the poem.

The stylistic foundation for the poem is Frank O’Hara’s “I-do-this-I-do-that” poems, particularly how, in “The Day Lady Died,” the street is a dynamic field that offers opportunities for reveries. O’Hara constantly digresses and reengages, but there is a kind of forward momentum toward the revelation of news of Billie Holiday’s death.

So, momentum and orientation play parts in the first stanza of “Studio Museum,” as does a certain self-consciousness—of eating standing up, of summer heat on the sidewalk—as well as connecting back to “When the Starts Begin to Fall,” which we had just seen, and specifically to the work of Kara Walker (the image of our shapes being burnt through onto rock as silhouettes).

That stanza resolves by evoking Glenn Kaino’s “Bridge.” In the process, I was hoping to show how language can fire synapses in the mind. As a runner myself, I relished the opportunity to go hand-over-hand with Kaino’s work. My mind set in motion a chain reaction from the artist (Kaino) to the subject (the iconic disembodied arm of Tommie Smith, gloved and gold and repeating) to the installation (a long, hanging, undulating series) to an object it evoked for me (banister) to wordplay that lands on a resonant connection (a banister from Tommie Smith to miler Roger Bannister).

Kaino presented one of the functions of art—a way to step up and see and be seen from a vantage-point—by creating a work that gestured toward the podium Smith and his teammate John Carlos mounted both in victory and in protest.

My hope is not that readers make every leap of that synaptic journey—which flashes by—but instead grasp how the residue of an experience informs subsequent environments, and how those new connections might tumble forth in words.