In Their Own Words

Holly Mitchell on “Nightmare”

Nightmare

The animal burdened

is cribbing on

a dank fence line.

She appears almost

elegant, ewe-necked

but fescue-footed,

when to the ground

& the meat of

her gored hooves

you inevitably look.

A militant horse

might fight & hasten

the breaking of joints,

yet this mare has

no kick. She looms

over lambkill, the moon

of her moon blindness

near opal, peering quietly

as the ring of ringbone.

That sound is her surra,

a ragged, swaybacked

way of telling you

she is still here

despite the stable flies

stuck on her hide

like beads unshaken

by vertigo. If you lean

close, you can hear

the undertone

of the warble fly

nested under skin,

making a whistler

of the riding horse

now so wind-broken

her breath is kept

in exile, heaving

as she mows this yard

in zodiacal light.

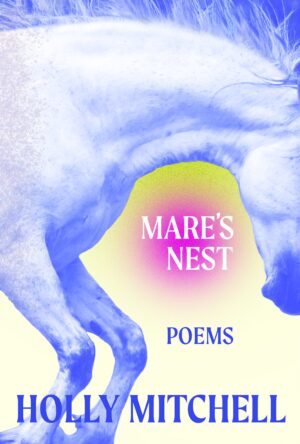

Reprinted from Mare’s Nest (Sarabande Books, 2023). Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

On “Nightmare”

This poem began as an abecedarian, a poetic form that plays with alphabetical order. I was reading Matthea Harvey and felt inspired to take a looser approach to the form.

I drew from a glossary of equine veterinary terms, pulling words that I liked the sound of whether they seemed familiar or fantastical. My family moved to a horse farm when I was a teenager, so I had some exposure to this world. The newfound experience of helping to take care of horses was heightened by that of gaining a new vocabulary to describe their lives. The language for horses is often old and concrete, unusual but rarely inscrutable, a treasure trove for a poet. I made a wordbank and pulled my favorites from it, roughly arranging them from A to Z.

As I wrote around the glossary words, I imagined a female horse, a mare, with all of these ailments, transformed into an impossible nightmare. She recalls solo horses in people’s yards in the South, like the neighbor's horse my mother doted on as a child so much that she told me about it decades later. Or those you might see on a drive through the country or, in my case, on the bus route at one of the stops closest to the river, where the kids might or might not come out when the driver honked. They were poor, yet there was their horse, tied to a tree.

This “Nightmare” is like a cursed figure in a myth. It ended up as the second poem in my book, Mare’s Nest, because it introduces “the animal burdened” and suggests a symbolic world beyond what happens in the poem. The nightmare dwells in someone’s yard, just “mowing the grass” in her retirement from pageantry and reproduction. The sacrificial mare, she reflects the anxieties of what can go wrong with an aging animal. Even when well-cared for, the body is specific and breakable.