In Their Own Words

Leah Naomi Green on “Field Guide to the Chaparral”

Field Guide to the Chaparral

The fire beetle only mates

when the chaparral is burning

and the water beetle

will only mate in the rain.

In the monastery kitchen, the nuns

don’t believe me

when I tell them how old I am,

that you were married before.

The woman you find attractive

does not believe me when I look at her kindly.

There are candescent people in the world.

It will only be love

that I love you with.

When we get home,

there will be our kitchen, the dishes undone.

There will be our bedroom.

What is it you eventually recognized in my face

that allowed you to believe me?

Beauty that did not come from you—

remember how it did not come from you?

As white sage does not come from the moon

but is found by it and lit.

The Buddhists say

that the front of the paper

cannot exist without the back.

Because there is a there,

there is a here. Chaparral,

the density of growth,

and the tattered chaps

the mappers wore through it

because they had to,

to keep walking without

being hurt. It is okay if we hurt

one another.

Chaparral needs fire

(the pinecones cannot open

otherwise). Love needs lover,

whose last lover was flood.

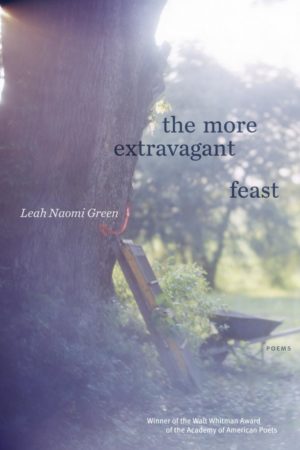

From The More Extravagant Feast (Graywolf Press, 2020). Reprinted with the permission of Graywolf Press.

On “Field Guide to the Chaparral”

I knew a monk in California who performed nightly prostrations to his difficulties because they were his greatest teachers.

“Field Guide to the Chaparral” began as a bow—as an attempt to look, without flinching, at the love contained in hurt, and the hurt contained in love—the startle and awe of love and hurt comprising one other.

Writing for me is often bowing—though not always to a difficulty—sometimes to great astonishment or delight. In revision I bow deeper, to try to “see again” and again: to try to see the teacher. I find it helpful to have the delineated rectangle: on the page, on a mat, kneeling and bowing become perfectly appropriate actions. The page is cleared for the purpose. It says look at this. You don’t have to look away.

When the poem sifted into couplets, reflecting duality, the underlying subject of non-duality came into focus, and I caught a glimpse of the teacher inside it: a glimpse of “the front of the paper” which “cannot exist without the back.”

I feel this non-duality now, in April 2020, in the middle of a pandemic and social-distancing, when it seems unavoidable that suffering contains much that is not suffering—gratitude, support, large-scale reflection—and unavoidable that respite can contain great anxiety. I prostrate over and over with no one else around.

“Field Guide to the Chaparral” is the first poem in The More Extravagant Feast, and it is the beginning of an arc. The arc of The More Extravagant Feast, at least the narrative arc, is that of two pregnancies. Those gestations, and the continual gestation of my own body by the garden and woods from which I live and eat, make real the questions of the larger arc: where is it that I end, and the child begins? Where do I begin? And you?

“Indulgences,” in the middle of this arc, explores non-duality through parenting and impermanence—the fleeting and infinite patience of a child’s body, and a parent’s creation around that body. “Last night/her small clothes/hung on the line waiting, / and I loved them there / all night, / their drying / in the quiet”—clothes which both fit the child and are already impossibly small, unable to contain her.

“Arrival”, which completes the book’s first section with a birth, focuses on the astonishment that, in gestating (and in the acts requisite to gestation, including eating) there is no discrete self at all, no arrival of anything: “It was before that, / when he and I / rubbed two cells together // because that was what we had. / No, before that too, / and never // was there a moment/when you were not / already // in the motion / of materials— / of love, which we call atoms // because we must / call it something— / turning to the sun ,// the seed that is the fruit / that’s already the seed begun…”

In “Field Guide to the Chaparral” the arc of the book begins, and the subject at its beginning is romantic love: learning to be seen by another; learning to see the self. In couplets, the poem prostrates toward the faulty notion that those ways of seeing can be separate at all.

Bowing, as low as my muscles will allow, to a difficulty does not make it go away. It makes me less afraid of it, able to listen for it— able, at least, to want to hear it.