In Their Own Words

Luther Hughes on “Near Sacrament”

Near Sacrament

Sometimes, it is a dream:

the robin’s slick song

paring back the morning—

it is not morning,

or, it is not like how morning comes,

as if water from a glass

tipped over, but it is how

I loved you, gradually

and then all at once.

Cherry plum trees

settling into their blush;

hills of sodden wheat;

this golden field

I can’t stop returning to:

you, naked, inching towards me,

an adaptation of tenderness

and force—

brief lights

that fall gently

from your hands.

If only the landscape were that simple:

pollen in the air, each breath

leaving the mouth like a man

pushed from a building—

no, no. He leapt.

To what do I owe your beauty

to which I never fully required,

and yet, while beneath you, is what bloomed.

This is how I began: as dirt

and desire, or simply a small river,

aimless,

but moving—

to where?

On "Near Sacrament"

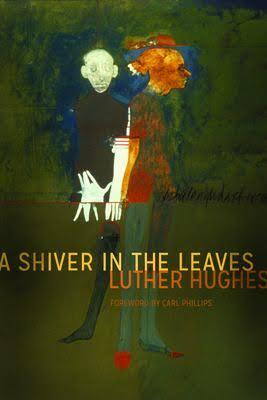

I wrote this poem during my second year at Cave Canem. During that week, I announced that my book—an earlier version of A Shiver in the Leaves—was “finished,” and I wanted to start focusing on love poems for a possible second book. That entire week, I wrote love poems about my boyfriend. It was a bit of a challenge for me because, at the time, I was really focused on other themes: depression, trauma, Blackness, death, family, etc. I wanted to push myself outside my comfort zone because I had begun becoming really invested in the ideas of love and what being in love forced me to consider about my own life in comparison to depression and suicidal ideation. I was interested in that tension even though I was sure these poems were going to belong to another book.

For the week, I had brought with me The Rest of Love

by Carl Phillips, a book meditating on love, divinity, and tenderness—to put it simply. While reading Phillips’s collection for the umpteenth time, I was pleasantly surprised this time by how he was able to incorporate the natural world into poems that work to interrogate what love is and means. This wasn’t something new; I’ve read poems like this before by Phillips and others, quite frankly. But, this time, for some reason, it struck me. It could’ve been because of my intention to write love poems for the week or maybe it was because I was particularly hyper-aware of the nature around me—the campus being tucked away in Greensburg in the midst of fields, birds, flowers, trees, animals, etc. I felt as though I was surrounded, in some ways, by The Rest of Love.

The poem kicks us off with the title, “Near Sacrament,” which quickly announces the poem’s restlessness or instability. The word, “near,” asks the reader to understand the difference between exactness and closeness. Coupled with “sacrament,” a Christian rite to the means of divinity and grace, the title is attempting to say something about wanting to be close to divinity but not being quite there yet due to this restlessness.

This continues with the first few lines of the poem: “Sometimes, it is a dream: / the robin’s slick song / paring back the morning— // it is not morning, / or, it is not like how morning comes.” It was important to start with restlessness or instability to highlight how difficult it can be to express one’s love for another; sometimes there isn’t enough language to express how you feel about someone. This is also why the beginning (or even most) of the poem relies heavily on imagery. The poem is built on the “failure” of language. Eventually, at least, the speaker is able to get it out: “but it is how / I loved you, gradually / and then all at once.” However, the speaker quickly reverts to relying on imagery as a way to express how they feel about the “you.”

The stanzas that follow mention trees, hills, and a field as a way to bring the poem back to a dreamlike feeling where the beloved—the “you”—is walking towards the speaker with “brief lights” that fall from their hands. It’s so dreamy. I love this part because it allows the reader to do with the scene what they will. Is it a dream, a metaphor, or a symbol? Either way, it can be read as a moment of tenderness and intimacy. The speaker becomes completely enthralled by this scene that they need to snap themselves out of it: “If only the landscape were that simple.”

The ending stanzas of the poem highlight the realities of what it means to be in love and what it means to choose to fall into it: “pollen in the air, each breath / leaving the mouth like a man / pushed from a building— // no, no. He leapt.” The line, “no, no. He leapt,” was my attempt at announcing the difference between falling in love and choosing to remain in love. Love, at times, can be complicated, and sometimes we—I—can find it so overwhelming that it’s the only thing thought about. What does it mean to “leap” into love? What does it mean when the falling is on your own terms? This part to the end shifts the poem into thinking about power and how it plays a role in love, intimacy, and desire. When the speaker announces their genesis story, they are thinking about where they came from and where love will take them. When we are born, we don’t know where our lives will end up. Every day is a new journey if we choose to take it. Love, if we allow ourselves to leap, will take us somewhere. It’s not important where we go, but that we choose to get there.