In Their Own Words

Nicole Cooley on “Downriver”

Downriver

the storm is a girl on the edge of fury

in a dress the color of lead not

the girl I once was too easy let’s talk about

downriver parishes no one knows the names of

not a spill of moonlight no cool loose dirt let’s talk

about a river thrashing blinking open no

lovely blur but a wrecked pink shotgun

splintered crushed yes I am talking about

dynamite yes downriver is a word take it

apart I am talking about the levee at Caernarvon

no metaphor only spill only break only explode

not edge yet how often I walked the Mississippi’s border

mud sunk swirl of storm no too lovely tall river grass

levee stunned open glow of a silvered moon between

split trees a body swept and dredged

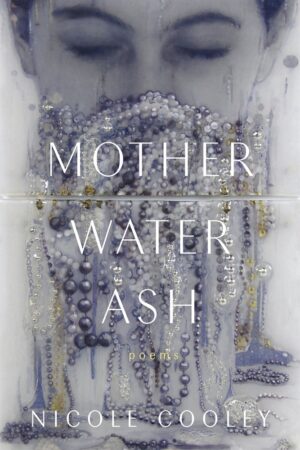

Reprinted from Mother Water Ash (LSU Press, 2024) with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

On “Downriver”

“I will die in this house.”

These weren’t my mother’s last words, before her sudden death in March 2018. We never had a chance to speak last words.

This is what she said to me on the phone on August 28, 2005, when Hurricane Katrina approached New Orleans. I was begging her to leave the city. My parents stayed and were lucky to survive.

Now, nearly twenty years later, my mother’s sentence haunts me. And they haunt my poems. Her words never appear in “Downriver,” but they were crucial to early drafts of the poem and still swirl below the surface.

“Downriver” is the last poem in my new book Mother Water Ash, which explores my mother’s death and the Gulf Coast’s destruction. I first learned of the erosion of south Louisiana as a high school senior, in my “Louisiana Ecology” class: we were told the state’s shoreline was eroding at a rate of one football field a year. For comparison, now we lose a football-sized area every 100 minutes.

But none of it—my mother’s words that August, my learning as a teenager of the coast’s erosion, the new horrifying statistic—appears in the final draft of poem. Yet all of it is crucial.

Let me explain. I am a very messy writer. In all other areas of my life I pride myself on being extremely tidy and organized. With poems, I seek out the opposite. I am an over-writer, a stuffer of pages in stacks, someone who is eager to write many, many terrible drafts and lower my standards at every turn. Working with the assumption that I won’t know what goes in a poem as I write it, I put everything in. I write anywhere and on anything—a receipt from my purse, a train ticket, my wrist. I avoid nice notebooks a

nd fancy pens. I most of all love a huge, chaotic mess that might turn into a poem.

For “Downriver,” I kept a file folder with more than thirty pages of handwritten notes. Material from articles and books on New Orleans, information on Katrina, and pages of my own thoughts and images. I let anything into the collection. My writing is a process of gathering, then sifting.

I first drafted an expansive version of the poem, more than ten pages long. I then chopped the poem down to its smallest size, six lines. Finally, I read over the long, chaotic version of the poem and the tiny version and started again. “Downriver” began to radically shape-shift.

This is how I broke the poem open. “Downriver” quite literally fractured into pieces, language ruptured by blank spaces and omissions, language not governed by punctuation.

When I read the poem now, I feel the presence of everything that ghosts it: from the Mississippi two blocks from my parents’ house, to Katrina’s landfall, to my parents‘ decision to stay in the city, to my mother’s death years later, to my own girlhood, to the Great Flood of 1927 in which the levee at Caernarvon south of New Orleans was dynamited to save white neighborhoods, displacing, and killing Black citizens of the city.

And as I revised, I began to see that “Downriver” is a poem about ecological grief, the mourning for the earth we feel in the face of climate change, and personal grief. How I might bring the two together became a central question. I want to believe a poem can be open to the world and let everything in.

I’ll admit I didn’t always write like this. In grad school, I’d often feel blocked and stifled when I sat down to write a poem, envisioning it as writing a “POEM” —with all the gravity that implied. Facing a blank screen or page, I thought I’d never find the magic.

But once I began my magpie-collecting of materials, my low-stakes drafting, my shape-shifting, everything changed. I began to see how a poem is an open rather than a closed system and how it can explore rather than settle questions.

“Downriver” is a poem that shows the mind in action, speaking to loss and landscape and the ways they orbit each other. I wrote the poems in Mother Water Ash to keep my mother and the Gulf Coast with me and to bear witness to grief.