In Their Own Words

Raisa Tolchinsky on “Solve For Me That Knot”

Canto 10 - Solve for Me That Knot

On “Solve For Me That Knot”

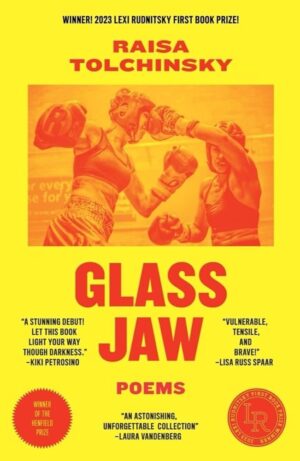

Much of my book Glass Jaw is interested in descent— in following the poem to the next level of poem—the boxing ring beneath the boxing ring, the fear underneath the fear, the helical story beneath the story. The shape of the spiral is what writing a poem feels like to me—the first lines are a surface to occupy my mind’s chatter as I search for what lives underneath.

“Solve For Me That Knot” first began as a poem describing a moment during my time training as a boxer in New York City. To be physically trained—to be coached (or to coach), is an intimate act, both physically and emotionally. I needed the bounded ring of the page to be able to work out the complexity of my relationship with the coach of this poem, who is a composite portrait of so many of the coaches who trained me.

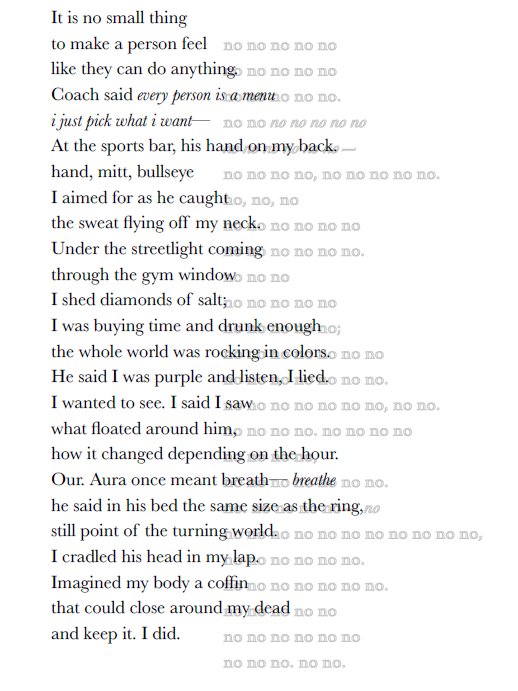

Many of the poems in Glass Jaw are angry. I wanted to make explicit the “shadow” poem—that beneath every line break, every edited word, the poem was really only saying one thing, forward and backwards in time. The two layers are the intellectual mind speaking alongside the physical body. In this poem, the mind describes and narrates, but the body is only ever saying: no, not that, not this.

Each poem in the second half of Glass Jaw corresponds to a canto in Dante’s Commedia, and in Canto Ten, Dante and Virgil have entered the City of Dis, the lower circles of hell. They enter a landscape—a cemetery—where all the tombs are open and on fire. This is the punishment for heretics: “Qui son li eresiarche / con lor seguaci, d’ogne setta (Here are heretics / and those who followed them, from every sect [Inf. 9.127-129]).” This canto is about the sins of the Epicureans, with a dash of Florentine politics, but I am mostly interested in the landscape of the cemetery. What an image! Open tombs, filled with fire!

The relationship between tomb / bed / boxing ring—all places where there can be a “fire” of sorts— animates this poem. In Dante’s canto, the Epicureans were punished because they pursued pleasure, as did the speaker of this poem.

Dante’s canto made me wonder: how do you “close” the image of an open tomb on fire? For me, it was by speaking the “no” the body always wanted to say. This “speaking” becomes the way the dead are able to rest in peace—the memory of a man and a sport I loved.

Works Referenced

Barolini, Teodolinda. “Inferno 10: Love in Hell.” Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2018.