Interviews

An Interview with Joni Wallace

I first encountered Joni Wallace's poems in 2009 when I was the judge for the Four Way Books' Larry Levis Prize. Her manuscript, Blinking Ephemeral Valentine, was one of the finalist submissions I'd been sent by the press. Reading it, I knew it was poetry the way Dickinson told Thomas Wentworth Higginson (L342a) she knew a book was poetry, "If [reading it] I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry… Is there any other way?" For the judge's citation, I wrote:

"In these poems, the valentine (i.e., love) is a many-faceted metaphoric machine that is endlessly active—forever drag racing with the dark—after which it sputters, clangs, trails off, goes out, and returns to post itself like a 'shadow pterodactyl.' …[T]he heat is fierce and fanatic: 'If it snows I'm dressed like Christmas, I'm lit, / I'm drinking Red Rockets and oh how they glare.' There's flicker and flame, and things flung: 'my goodbyes, flywheels and marigolds all, of those midair/still hanging souvenirs and petals I'll press into pies.' These poems are brilliant: the language is excited, the syntax ever-shifting, the images inventive. Every line feels irrefutable, and charged— electric, like love is, and glittery, like valentines are."

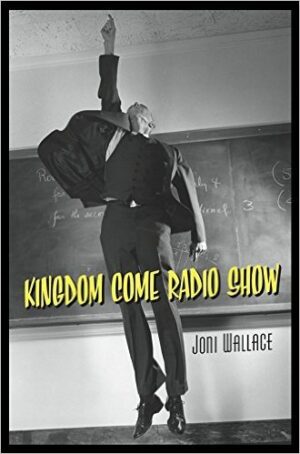

Wallace's new book is every bit as linguistically nimble as the first. There is, however, in Kingdom Come Radio Show, a new solemnity. J. Robert Oppenheimer's atomic bomb casts its shadow across the moving landscape of the present where deer graze, clouds roll in, and a song on the radio reminds the speaker of a long-ago car ride across the same territory. The threat is no longer that love might go cold but that everything dear to us could be blown to the high heavens or eroded by heedlessness. The poems are tender, prescient, formally adventurous and … Keatsean in their beautiful and painful truths. The photographic fragments and linked sound pieces form a documentary backdrop; the poems act as a voice-over urging us to look and to listen.

"Oppenheimer, pacing at dawn, smoking, working the equation that says the atmosphere will/will not ignite when the gadget blows straight up into Kingdom Come. In the tilt shot, Kitty Puening Oppenheimer, drink in hand, clink, clink of ice against glass. … Cut to a long drive along a stretch of road, almost-dark, the percussive hiss of cicadas, stereo. Hank singing on this road of sin you are sorrow bound."

Mary Jo Bang: In "Twilight Amphitheater," the first poem in Kingdom Come Radio Show, you mention recordings of J. Robert Oppenheimer speaking "under this same expanse"? Did listening to those recordings prompt you to write the early poems that eventually became this book? And if not those recordings, what did trigger your interest in Oppenheimer?

Joni Wallace: I grew up in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the Manhattan Project unfolded decades earlier, and I think that complicated sense of place has been a defining identity for me as a writer. Los Alamos is a place of government secrets: war remnants, streets named for bombs and the scientists who made them, abandoned gun and guard towers. School days were punctuated by intermittent sonic booms (which I now realize must have been military jet fly-overs), wildlife areas fenced and marked "Restricted Area." There was talk about Acid Canyon, an area so contaminated by nuclear waste that it became a no man's land. This contrasted with the natural beauty and drama of the Jemez mountain range, the endless mesas, Aspen groves, light and cloud play, million-star night shows, an abundant presence of wildlife. To grow up there was to carry a sense of the war-time opera, this staged against the mountain pastoral, glimpses of the inner workings of a nation's war machine appearing and sounding through an ever-present animal chorus. Inherent dissonance of place. I felt, even as a child, a sense of witness, even complicity, in the darker moments of human history. It's like CD Wright says so beautifully in one of her most recent essays, "imaginatively, the land is reminiscent in detail of all that ever came of its issue, was built on its foundation, or came to great harm on its surface."

I made some early attempts to write about the Project; I didn't consider these particularly successful. Then a few years ago, I stumbled upon some home movies taken by one of the physicists working on the Project, Hugh Bradner. He was documenting the lives of the scientists, their wives and families, during the Project, permission from the United States Army. Robert Oppenheimer, who led the Project, makes some appearances in the films. Those recordings got me thinking about the whole spectrum of record-making, official and unofficial, and the documentary nature of poetry and art. What would the poetic document of place, history, the making of the bomb, look like? This was interesting to me, and made an opening, a window into a conversation.

Mary Jo Bang: I'm fascinated by the word "oneirographer" in the poem "Oppenheimer Drive"—especially since it's linked to threnody, an ancient song of mourning ("If I am oneirographer, beginning-, middle-, end-deer, / a threnody"). I was unfamiliar with the word and could only find the suffix "oneir-"—related to dreaming. Is the word oneirographer a neologism and meant to be read as someone who records dreams? The extreme specificity of it makes me feel that it's an important moment in that poem, and possibly, even in the book.

Joni Wallace: Yes, a neologism for someone who records dreams. The word goes directly to the idea of poetic documentation. In grad school, I read Hélène Cixous' Dream I Tell You and was really drawn to both its strangeness and gorgeous language, the associative quality of it. There is a similar quality in Berryman's Dream Songs (another literary touchstone of mine). "Oppenheimer Drive," where the word appears, is the poem that began the book. I like the idea of that poem as a "dreamoir" racing toward a secret that can never be completely revealed. It felt to me like a ride on a ghost train, the train moving through dream-like vistas, time-warps, soundscapes, but anchored in that sense of place: lit city on a mountain. A dream's trajectory originates in the unconscious, is strung together by little lights of association, and I hope the poem works that way. In my attempt to define the speaker, "oneiographer" seemed the most precise.

As for "threnody," it is a lament, from Old English dran, "drone," to murmur, or hum, from drunjis, "sound," from Greek tenthrene, "a kind of wasp," all of which are apt for the landscape and the project of the book. I love how the word's etymology makes its own ghostly tracers: lament, song, murmur and drone, insect buzz.

Mary Jo Bang: One doesn't usually see photographs, another kind of specificity, in a book of poems. Are you suggesting that image and metaphor, and other traditional figurative strategies for making the reader see inside the speaker's mind, are no longer adequate to the task? Or just not adequate when the subject is the atomic bomb?

Joni Wallace: I wanted to use everything available to me in the act of documenting. I see the photographs as found pieces (some historical, some personal), fragments of time/place brought forward into the future. I remember when discussing The Eye Like a Strange Balloon, you talked about the suspension of time that occurs when the viewer views the photograph, what Roland Barthes calls "punctum," and the unique emotional weight photographs carry because, although they represent a stoppage of time, they also encapsulate the passing of time. I think of that as a kind of inherent elegiac quality. And some of the photographs are just meant to reflect, to make different kinds of mirrors: Meret Oppenheim's "Glove," for the fact of Oppenheimer's mother, Ella Friedman, who was born without a right hand and always wore a wooden prosthetic and the glove. Oppenheim, a French surrealist, seemed like a compatible ghost, both her work and the echo in her name (just a lucky coincidence, that).

Mary Jo Bang: In the book, is nature what links the "Oppenheimer" era (and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki) to our terror-infused moment? Is that the role of the deer in the poems, to remind us that while nature is persistent, it's also vulnerable?

Joni Wallace: Nature certainly is a link between the two eras. The Doomsday Clock, the symbolic clock created by a group of scientists who had participated in the Manhattan Project, is set to the reflect the danger level of annihilation in the nuclear age. After the bombings, the clock was set to 6 minutes before midnight. At the height of the nuclear arms race, the clock was set to 3 minutes before midnight. It has since been moved back, as far as 7 minutes before midnight, in times of peace. This year, the Science and Security Board moved the clock forward to 3 minutes before midnight again, noting the very high probability of looming environmental global catastrophe. (As a side note, though, I don't think the nuclear annihilation scenario is over, it just isn't in the forefront of our thoughts).

The deer of Kingdom Come Radio Show are the familiars in my childhood pastoral, creatures of wonder, ephemeral appearances at the edges of woods. The deer are a mirror; they are an animal lens. They are both witnesses to and victims of human events. Global citizens. They stand at the tipping point. They are stalking horses, carriers of information, harbingers of both what has passed and what is to come, tricksters, shadow-lings, extravagant others, prisoners, protesters, babies.

Mary Jo Bang: What would you like readers to know about Oppenheimer—a name some younger poetry readers might not recognize? And what about his wife, Kitty Oppenheimer? Is she the classic 50's woman, bound by convention to a fraught marriage, in her case with an unfaithful spouse who just happens to be "the father of the atomic bomb"? Or is she more complicated than that?

Joni Wallace: Robert Oppenheimer's name is freighted: "Dr. Death," "Father of the Bomb." But the labels are reductive, reflecting only the shallow narrows of his story. There is a far more complex and terrifying view: Oppenheimer as human. Fallible. Brilliant. Innocent and culpable. He was a rock-star, as all physicists were at the time, one whose graduate thesis arguably laid the groundwork for the discovery of black holes, only then to be caught up in an escalating war theater. He facilitated the making of the bomb; he did not do so alone; many others would have happily stepped into his shoes (Edward Teller, for one). He's quoted as saying, about the making of the bomb, "You see something technically sweet, you do it." He saw his role as scientist, not the Major General or President, not member of a war council, on whom he believed the decision to use the bomb rested. One might assume personal ambition, the desire for fame or recognition, motivated him to lead the Project, and there is evidence of that. We also know he immediately regretted his part in the bombings and the horrifying devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that he felt he had blood on his hands, and that he wished to be a force for world peace moving forward.

But maybe most interesting to me is that Oppenheimer's story is the stuff of Greek tragedy: hero presented with extraordinary circumstances, the fatal character flaw that predicts the tragedy, follow the dots. The twist, though, is that the story of the man, peace and order cannot be restored. Instead the human race is launched into the atomic age, one in which the means to our complete annihilation is forever within our hands. So Oppenheimer gets no ending: his ghost continues on. As with all ghosts, he goes about with his unfinished business: maybe an atomic wish to re-arrange himself inside the past. Maybe a wish to be the boy in the last section of the poem, "Oppenheimer Drive," on his arm tattooed words "Live Right. Do No Harm." Maybe to be merely the song inside an atom. It is a cautionary tale. One in which we might see ourselves as the tragically and deeply flawed heroes, our actions and inactions ushering in the Anthropocene and the shadow of global environmental ruin.

Katherine Puening Oppenheimer ("Kitty") is an extraordinary character. She was married and divorced three times before marrying Oppenheimer, the second time to a communist party member, Joe Dallet. Kitty moved to France with Dallet; he was later killed in the Spanish Civil War. She returned to the United States to marry her third husband, a radiologist, and to study botany at UC Berkeley. There she met and had a torrid affair with Robert Oppenheimer. After becoming pregnant, she divorced her husband and married Oppenheimer. She was his confidant, herself a scientist, working briefly at Los Alamos as a lab technician. Her personality is described as "fiery," and hard-edged, and she's often been criticized for her apparent ambivalence toward the tasks of mothering. Oppenheimer may have had affairs; it seems equally plausible Kitty did. And it was Kitty's checkered past and ties to the Communist Party, particularly to Steve Edwards (a close friend and probably former lover), that followed Oppenheimer, and were used against him in a McCarthy-esque Atomic Energy Commission hearing that named him a threat to national security and cost him his security clearance in 1954.

Mary Jo Bang: Several poems include links to sound pieces. Do you hope readers will listen to these pieces while reading the poems? Or after reading them? Can you talk a bit about "Grass, Detail"—one of the pieces that isn't paired with a written poem, although I sense it is in dialogue with that same line in "Twilight Amphitheater" that I mentioned before: "[Oppenheimer] speaking under this same expanse, in this same terrain, some part of the man, a history, seems forever caught in the pines, the blades of grass." Are we meant to read the fragments and the musical counterpoint as what one might hear in the grass, if only our ears could perceive the supernatural?

Joni Wallace: Sound was yet another way of making the record, an acoustic dimension. In some cases it was a way to resist language entirely, in others, the official language used in government records. That felt subversive enough. I approached each sound piece as a poem, albeit poems composed of air molecules moving. I like the idea that the brain processes sound differently. I hope they add another dimension to the poems, one worth the effort of listening to them. They appear in the book on the page in the order I envision them being heard: short interludes at the end of each section.

As for "Grass, Detail," yes, the piece is in dialogue with Twilight amphitheater and has a musical counterpoint—melody—to it. The other sounds—record player, radio tuning, cello bow—on wood bookend the piece and set off the word "grass." And then I just tried to deconstruct that word by the sung sound, the vowel, from the low (å) to the dark vowel below it, æ, and finally to the vowel-less of insect sound (bow on cello back). Those are the components of the piece, and its trajectory. In its own way, it follows the path of that word "threnody."

Grass has no language as we traditionally understand that concept, yet grass certainly emits sound in its movements, in the flow of chlorophyll, in the divide of cells. Scientists are able to listen to the sounds of cells dividing (cell wall vibrations) in order to make cancer diagnoses. And there is evidence that plants interpret sound: a certain kind of weed, when played sounds of caterpillars chewing, secretes a chemical intended to repulse them. So I suppose the piece "Grass, Detail," is also an imagining of what grass receives, what it might transmit back to us, under the weight of a body, a 100-ton thundercloud, a megaton bomb.

* * *

Mary Jo Bang is the author of seven collections of poems, including Elegy, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her most recent collection, The Last Two Seconds was one of the New York Times Book Review's Best Poetry Books of 2015, one of Flavorwire's Best Independent Press Books of 2015, and one of Entropy's Best Poetry Books of 2015. Her translation of Dante's Inferno, with illustrations by Henrik Drescher was published in 2012. A forthcoming book of poems, A Doll for Throwing, will be published by Graywolf Press in 2017. She teaches at Washington University in St. Louis.

Joni Wallace is the author of two books of poetry and a chapbook: Kingdom Come Radio Show (Barrow Street Press, 2016), finalist for the Colorado Prize, the Besmilr Brigham Award, Word Works' Washington Prize, and AROHO's To the Lighthouse Award; Blinking Ephemeral Valentine (Four Way Books, 2011), selected by Mary Jo Bang as the winner of the Levis Prize; Redshift (Kore Press, 2001), which garnered a fellowship from the Arizona Commission on the Arts. She lives in Tucson, Arizona, where she teaches at the University of Arizona Poetry Center.