Interviews

Interview with Milena Marković

from deca / children

take nebojšina street instead

yes, take nebojšina

I muttered to myself

on the left is a park

in that park oleg’s grandmother saw

people flying

they were flying effortlessly everywhere

from the bombs and there were arms

and legs in the trees

now the park was under a white clean snow and deserted

there weren’t any arms or legs

now was the most beautiful time

and then

you will see the black george statue

he was six feet six inches tall

he had beheaded many men

with a scimitar

look to the left there are hospitals

grandma milka took your dad

to exercise every morning

there they were crossing the street she would buy him juice

she’d sit down on the bench and light a cigarette your dad

would struggle to stab

the straw through the cap

he’d smear his pudgy hands

with thick sticky

peach juice

he’d look at his mother and she’d find

water to wash it off with

and wash and kiss his face and there they’d run

toward grandpa who’d be waiting to give them a lift

look son

aunt daša in her boots swished her hips

in a white flowing dress

wearing a red belt

men would honk after her she was so beautiful

she’d bring hot pogačicas and yogurt

to eat on a bench

then she’d go to study at the national library

as you pass by the temple

filled with gold

look up jesus said

suffer little children and forbid them not

to come unto me

son carry vinjak and beer in your coat

on your way to čubura drink the vinjak

when it warms your blood

cool it down with a cold beer

you will see me on the bench

sitting on nikola’s lap

the temple was still being built

we were laughing

Translated from the Serbian by Maya Teref and Steven Teref

Reprinted from deca (children) published by Lom Publishing House in 2021.

Unlike many contemporary American poets, probably me included, Serbian poet Milena Marković doesn’t problematize the fact of being a mother and a writer. Nor does she sentimentalize childhood. Or war. There’s huge passion in her poems, and yet, for a poet who’s also a playwright, one who says she adores melodrama, there’s an absence of lament, regret, histrionics, so that in a poem called “the bombing,” the NATO bombings of the 90s are just the background noise in the carnal life of a teen: “my hair is filthy there is no water / my scalp is bleeding from scratching / I’m waiting for summer so I can wear a tube top / and go to the sava.”

As an answer to one of my questions below, Marković says, “A lust for life.” That phrase might evoke for you the Iggy Pop album with the beautifully spare lyrics co-penned by David Bowie, or more recently, the Lana Del Rey song. It also evinces the archetypal fixation on youth in Marković’s work. While this interview has been condensed, on the afternoon we met in Belgrade, she talked about the Jim Jarmusch documentary Gimme Danger, as well as Link Wray, MCR, Patti Smith, Bo Diddley, and more. She loves American music. And American writers. She quotes Langston Hughes in Serbian from memory. Like Hughes’, her poems are vertiginous, simple and not simplistic. And yet they also have a seductive ugliness, like in this excerpt from the middle of “bird eye on the fence”:

it’s over with the singing

it’s over with kissing

ears grow, eyes grow, stomach grows

and mountains, so distant

and roads and that sky

and everything passes, yet the big ass

the big ass swallows us all

the big ass, monstrous

the bird eye on the fence

says

you’re shit

your ears, your eyes

A selection of Markovic’s poetry, sympathy for the salami, which is newly translated into English by Maya Teref and Steven Teref, hurtles through a lifetime of reading and of living. At first encounter, I thought to describe Marković’s poems as a mashup of Dean Young (the fluid, whirling lines, the Romantic stance) and Olena Kalytiak Davis (the ostensible badassness), but I’ve since decided that describing her in terms of contemporary American poets is the wrong move. I recently read an advance copy of the Terefs’ translation of her relentless novel-in-verse children, which tells a version of her life story (and won the Serbian equivalent of the Pulitzer in 2021). At age 20, she gave birth to her first child, and, as she said to me, “and so then you’re a mother, and that is the beginning and the end of it, full stop.” But children is about more than interrupted youth, and I can’t get it out of my head. One reason is that this tonally nimble book reveals to me my American pieties and shows me how we might adhere to our principles without steering our literature towards them. I see us bringing the moral clarity we’re demanding in the justice system into literature. Ok, that’s where we are right now. But Marković is elsewhere. Her lines in this book are so clean and precise– they belie the maelstrom of her rich and tangled feeling. I want my literature (and my rock and roll) to never ever be moralizing. Marković’s lyric I is far from a position of knowledge or judgment—it is all feeling and nerve and wit. Her suffering is not a lesson—it’s a poetic energy.

—Darcie Dennigan

DD: I am wondering: which age do you feel you are right now?

MM: I feel I am 29. I have been 29 for years. Sometimes I do realize how old I am: I'm 50, but– 29. Maybe 30-something when I'm mature. Before that it was dark times, but now 29. This is me personally, not the “me” concerned in the book: I am 29

DD: Do people separate you, Milena, from the Milena in your poems? And to what extent do you want them to?

MM: I don't believe in “autofiction.” That word is extremely inaccurate. Every solid writer writes from personal experience. Even if we look at a genre writer such as James Ellroy who was obsessed with the death of his mother, we see that his work is from the point of view of his personal experience. Everything he wrote he wrote “on the bones of his mother.” Only through complete self-denial and diving into yourself, can you illuminate the truth for mankind. Balzac and Stendhal, regardless of their plot points, were the representatives of an epoch in which a colonel became an emperor. Their most central feature was their ambition. And that is, again, personal.

I don’t separate myself from the speaker. We are mutually informed.

I was writing children for a long time, and it had a different shape until I read Knausgaard’s My Life. And then I said to myself, OK, it’s possible to do this in poetry. So I put concrete names of people in the work. I share a language with Knausgaard.

BUT I don’t include banal exposition. children is not an exposé, I’m not interested in saying the name of this guy or that guy in it– which is not a question of intimacy. Take Byron and Augusta Leigh and their relationship…. After a couple of centuries, someone wrote a biography of her, but I don’t need the close story. It’s his poems that count. It doesn’t matter whom the poem is about, the only thing that matters are the feelings these poems invoke in the audiences.

Or you could say everything is autofiction. Some literary people use the word like it’s a pejorative. But in my view, something either is literature or is not literature.

Absolutely, I changed a lot of the details in children. I did what I needed to do. If I have to put something happening here and not there, I will. And yet nothing in that book is false, everything is true, because it’s artistic truth.

There was some hellish internet cacophony regarding children and the way I talked about my family. These readers were in a present without any continuity, like Dante’s Inferno repeating continuously, they were recycling confusion. They were like, “Oh what is this way she is writing about her son? What is this way she is writing about her mother?” And I was totally thinking, Have those people ever read a book? Have those people read any book in their life? Because I cry for my mother. Yes, I’m very angry with my mother because she did not save me. I want her to save me and she can’t now, she’s sick, and I cry to her as if to god, why have you forsaken me—that’s the way I cry for my mother in the book. I don't know that I can even take one step in a day without my mama.

DD: When you’re writing, especially about your family—parents, siblings, children—does the awareness that they will read it ever enter into your process or influence your choices?

MM: I’m not interested in what my family thinks. They read my books and they are fine, they aren’t petty. But on the first day I tell my students: “You don’t have a mother, you don’t have a father, you don’t have a sister, husband, you have a blank paper. You can be totally free and honest or you’re not a writer–believe me, it is not possible.”

You do not become a writer because of your experiences or the society you struggled with growing up. Those in the postal service or military or law also have personal and societal struggles. You become a writer because you are condemned by or gifted by a special type of sensitivity, because you are a medium for the feelings of all the people you observe. The conceptualism of this age brings cheap points for those who fake radical experiences. Over time it will become clear that this wasn’t worth much.

I don’t write about the kids, about a life which is not my own. But also, that is the question: Is your life your own, or is that an absolute lie?

That question is also one of the main topics in children. Not because of any political system but because of the nature of freedom. Freedom does not exist. The only people who are truly free are maybe monks. If you want to be truly free you do not love anyone.

But on paper I'm totally free. It is the only place.

DD: I can tell from your poems that you don’t like false sentimentality, or kitsch. But you have said that you adore melodrama– what do you mean by that word?

MM: Melodrama is the pursuit of happiness. The most fundamental difference between melodrama and drama, which entails the precondition of the tragic, is that drama is always a pursuit for meaning.

The basic elements of “noble” melodramatic principles were established in the 18th century, and they are very important for European literature—Dickens, Jane Austen, the Bronte sisters. It was very important for me when I realized that, at this point, literature, even philosophy, started to introduce the concept of happiness. This begins with Kant. And melodramatic principles are also present in great American literature, such as the work of Carson McCullers or Mark Twain or Harper Lee.

In their work, the man is in the center of all things, the human being is cosmos.

Sentimentalism is different from this because it’s fake, these are fake currencies, fake feelings, kitsch, this is a deception. Melodramatic principle is honest, powerful, and noble. My poetry plays a lot with melodramatic principles, which is quite rare in poetry in general.

DD: There’s a line in children I like a lot: “there was only one body and I was in it”—I see your poems (the individual ones in salami too) as part of one body– one muscular body—without scaffolding, episodes, beats, chronology. All is immediacy.

MM: I try to be ecstatic. There is snow falling on Nebojšina street in the same park where, yes, people’s arms and legs were flying off from the bombs. My work is a confluence of real events, memories, associations. Everything converges, and I feel a sense of belonging to a space that I never left. These layers of history– they’re not acquired or learned. They’re not constructed. They’re a bodily sensation. Essential. Anachronistic. It’s a part of me without my choosing it. –And by “anachronistic,” I mean we are not human beings at only one present point in time, no, we span time.

DD: Your poems talk about women and girls being desired and desiring men in complex ways. Even when there’s real abuse from your grandfather, how, and why, do you avoid victim/villain paradigms?

MM: It’s a matter of lust for life.

My family is Serbian—from central Serbia, Kosovo, and Montenegro–and in these societies there is an undeniable link between the patriarchal system and lust, between what is forbidden and an amplified desire. Fellini, Antonioni–extremely sensitive film directors—came from such a society. And you don’t feel like a victim at all. I have never felt like a victim.

This family I come from was actually very dramatically cursed. They were all extremely beautiful and, some of them, wicked. They lived a close-knit, tribal, passionate, hard life. Concerning grandfather: it’s very complicated. Everyone liked that man. He was a very charismatic man. On the other hand, he probably had a very severe case of PTSD—he was a veteran of WW II. When somebody asks me now—or asks us, all of the children, the other generation too, because he probably did that all the time—why didn’t you ever talk about what he did? Well why didn’t we? It’s not so simple. It’s not only a matter of a patriarchal system. It is a tribe. We loved him, we protected him.

DD: At one point in children you call yourself “riffraff from New Belgrade.” And as we’re talking, you’re bringing up Charles Bukowski, Iggy Pop, Jack Kerouac, Daniil Kharms and others who, even among other artists, have a maverick essence. How important to your poetics is the idea of being an outsider?

MM: There are multiple layers here. I’m interested in archetypes. And the archetypal outsider, with a resistance to conventions, is something I connect to my generation, which felt classless and socially mobile. My mother was extremely low class, my father was from a peasant class, it did not matter. But–it’s not “however” it’s “but”—at that time here, there were no obstacles, the state policy was emancipation, everyone got the same education so there was no social differentiation in speech, my mother was taught Russian literature and language in a primary school, I mean she was hungry but no matter—but I went to the Fifth Belgrade Grammar School, which is an elite high school, and I found myself among people who were from this elite class….I had complexes because of that. Due to my insecurities, believing I would never be able to reach their standing, I started to consume nightlife and music and everything that I could. I am fifteen, sixteen and seventeen and I know everything.

I was also reading like a dragon. Especially poets I thought of as avant-garde, alternative, on the margins. Russian romantic poets. I mean, you have this guy Roald Mandelstam. This Roald Mandelstam who was a lunatic. Maybe schizophrenic. His themes are very dramatic, kind of classic things, love, loss, they have repetition, clichés, street speech, but they are very warm, emotional, they are not detached and cold. His was a lowering of the high style of poetry and at the same time elevating the low life… It’s brutal writing, it’s infantile writing. It is both a travesty and a burlesque. He wrote lines like, “Your dead lips will be kissed by a white night”—his poems are all kind of a juxtaposition between something sophisticated and something raw. So, when I was 16 this is what I was reading, and through it, I found the metric flexibility, the poetic language I needed.

But my own “alternative presentation” was not a pose, it was a statement. I had this famous teacher at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts who also cultivated an elite presence. He would switch between Greek, Latin, and French and people liked that, but one day I asked him, Are we here to do needlework or to study drama?

I had another professor, a famous film director, Žika Pavlović, who loved me very much and I loved him, but at the same time I was looking at him and these other professors and thinking, These guys in socialism, they are all dissidents and yet they’re living in huge apartments with state jobs and I am living in a small apartment with my mother and father and sister and brother, and then my sisters’ kids were there too, and every weekend there were some relatives sleeping over. My family was intelligent, but you know, we had crates of sour cabbages on the terrace. My family still has that apartment and when we were there a few days ago my brother said to me, “Why would we never sit on the terrace when we were younger?” I told him, the terrace was our cabbage refrigerator, it was filled with cabbages, and with laundry, how the fuck did we all manage to live here, sometimes 10 of us?

So I envied Žika—but now I have a huge study in a nice apartment and my students must envy me. Recently I asked one of my students about why a character was doing something in a story he wrote, and he said, “It’s because she can’t afford cigarettes,” and he’s saying that as he’s looking at my expensive cigarettes. So, I’m not riffraff anymore, I’m a dainty lady.

DD: Your poems don’t use capital letters or punctuation–is that a performance of this idea of anti-elitism, of “Are we here to do needlework or study drama?

MM: No, it’s not at all. It’s just a matter of versification. I am very interested in achieving a certain level of simplicity. I want to do it that way because I want it to be one sentence. I am trying here to achieve the effect of leaving the reader breathless.

My teachers in simplicity were John Donne and Heinrich Heine. Shelley, Keats, Pushkin: They were gods, but they were not my teachers. Then, then, I discovered the Russian avant garde and Russian brutalism: Kharms, Alexander Vvedensky, Nikolai Zabolotsky.

Female authors? Sylvia Plath’s Bell Jar. That was…wow. I never found her poetry ecstatic, maybe because I read only in translation, but I found ecstasy in her novel. Mary Shelley, Marina Tsvetaeva. Lucia Berlin, Christine de Pizan. I like Sappho. I adore the Bronte sisters. The way the Bronte sisters wrote about sex– they are deeper and darker than half of the 20th century writers. They’re more serious about sex than Henry Miller, whom I don’t like.

But if we’re talking about writers who were my teachers, I have to say that there aren’t really female authors among them. Maybe that’s a topic for me personally to explore. But I don't see it as important. I am interested only in craft and language. Not subject matter.

DD: But does being a woman come into your writing? Your poems are often so visceral, as if you write them with your whole body.

MM: It's possible but I cannot separate it. I don’t experience that as a writer—and I don't experience that as a reader. I don't choose what I read based on ideology; that is not how I experience writers. I don’t like the term feminine writing/women writer. I’m an animal. When you demonstrate such insolence as to imagine that you can become a writer, then you’re in the game with the greatest. And they can be men, women, or demigods like Shakespeare, Dante, or Tolstoy.

(This interview was conducted mostly in person, in English and Serbian, in a cafe in Belgrade, with translation help from Maya Teref, Steven Teref, Vukan Marković, and Aleksandar Bošković.)

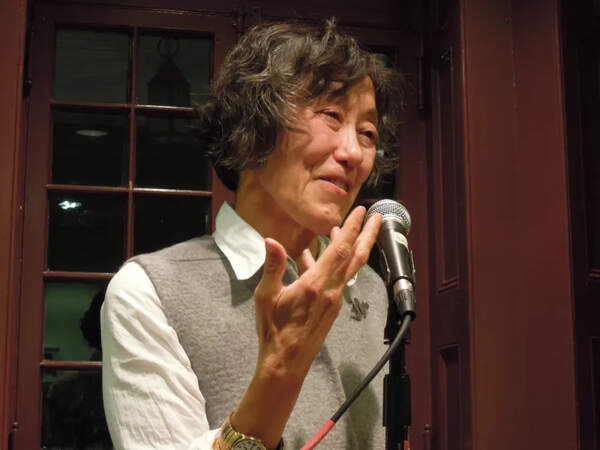

Milena Marković is an award-winning Serbian poet, playwright, and screenwriter. She has published seven poetry collections; her latest collection, deca (children), is a book-length poem published in 2021. Deca recently won the NIN Book of the Year Award, the Serbian equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize. Her plays have been staged across Europe and in the United States. She has also written screenplays for film and TV, such as Patria, winner for Best Screenplay at the FEST International Film Festival.

Darcie Dennigan is a winner of the Poetry Society of America’s Anna Rabinowitz award and the author of four books of poetry—including the forthcoming Commander!. Her manuscript Little Neck was a finalist for the New Directions Novel Prize in 2023, and will be published by Fonograf Editions in Fall 2025.