Interviews

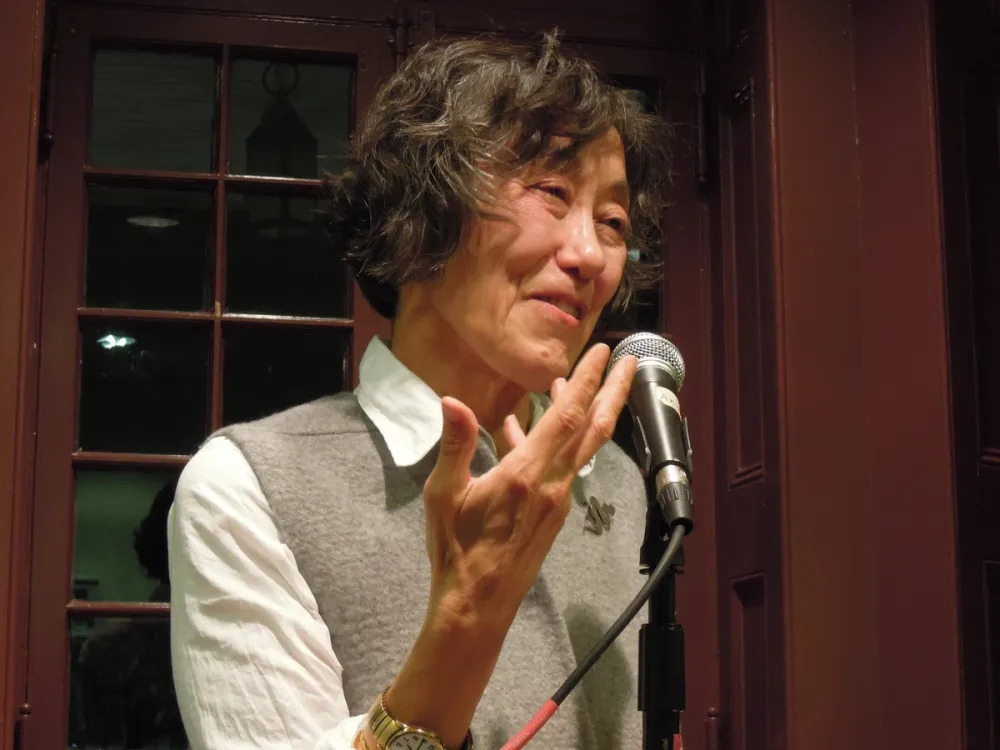

Interview with Mei-mei Berssenbrugge

The editors of Other Influences, Marcella Durand and Jennifer Firestone, conducted the following interview with Mei-mei Berssenbrugge at the Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts at the New School after Berssenbrugge’s class visit to Feminist Avant-Garde Poetics on October 12, 2019.

This interview is reprinted from Other Influences: An Untold History of Feminist Avant-Garde Poetry with permission.

Other Influences: You are what we think of as a visionary writer, unique in your own aesthetics, and yet you have roots in multicultural poetics and Indigenous poetries (including your relationship to the Asian American Writers’ Workshop in its early years), as well as in language poetry. How did these communities influence your thinking and work?

Mei-mei Berssenbrugge: After receiving my MFA from Columbia University in 1974, I was invited to multicultural writing conferences in Michigan and Wisconsin, where I met Rudolfo Anaya, Jeff Chang, Frank Chin, Victor Cruz, Phil George, Lawson Inada, Ishmael Reed, Simon Ortiz, Leslie Silko, James Welch, Shawn Wong, and Al Young, all of whom influenced me, particularly Ishmael and Leslie with whom I developed lifelong dialogues. We became a loose movement of many, many writers. I published poems in Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian-American Writers, Quilt, The Big Aiiieeeee!, The Greenfield Review, The Yardbird Reader. I read Gidra, Akwesasne Notes. I felt I’d connected with a more vital source of literature than in my writing workshops, and I embraced the revolutionary energy aimed at the literary establishment. That year I moved to New Mexico and deepened my friendship with Leslie, who had grown up at Laguna Pueblo. She was writing her great book Ceremony then. Leslie sent me Remarks on Colour by Ludwig Wittgenstein, which shifted my reading toward philosophy.

In the 1970s, when I published Summits Move with the Tide, only a couple of Asian American poets were known to have published, and I wanted to help Asian American writing be better known. Frank Chin directed my play One, Two Cups, which was about my friendship with his wife, Kathleen Chang/e, the performance artist and activist. It was presented in New York City by Basement Workshop, the first Asian American cultural organization on the East Coast, run at that time by Fay Chiang. I collaborated with Theodora Yoshikami, the founder of the Morita Dance Company, the first Asian American dance company, on a trilogy of dances commissioned by Basement. Basement was an exciting, innovative, freewheeling community of artists in various disciplines. I like to think that spirit passed to the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, which started in the 1990s and which has continuously nurtured Asian American writing and diaspora up to today. When I first described how “multiculturalism” influenced my writing, I would say that I’d met writers who had “stories to tell.” Maybe I meant a kind of vitality or “voice” and also a political and literary radicalism that continues subliminally in my work. Later, I taught poetry at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, which had this same spirit; there, Phillip Foss, Arthur Sze, and I cofounded Tyuonyi, a magazine focusing on avant-garde, multicultural poetry.

As for language poetry, I knew James Sherry when we were undergraduates at Reed College in the 1960s. After college, he moved to New York City, where he founded Roof magazine and Roof Books and produced the Segue Reading Series at the Ear Inn that continues today at Artists Space. His loft on the Bowery was a salon for language poets. I went to New York several times a year eager to absorb as much “new art” as I could, including language events. This was the late 1970s to the 1980s. I absorbed ideas of deconstruction, left politics, appropriation, abstraction in poetry, and I read widely. I met Charles Bernstein and Susan Bee, and we developed an enduring friendship.

James told me about Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror by John Ashbery. I learned a looser kind of unity through voice and collage, and a profound vernacular. I met Barbara Guest, because we had the same psychiatrist, and we became friends and shared each other’s writing until her death. Anne Waldman invited me to hear Jackson Mac Low at the Ear Inn, and my friendship today with Anne continues to revolve around “news” in poetry. Still, I don’t consider myself a Language or New York School writer.

In San Francisco, I met Kathleen Fraser, founder of the journal of experimental women’s poetics, HOW(ever), where I published. One of my themes was to “feminize” the rhetoric of scientific language in poems. Kathleen told me about many women writers, including Lyn Hejinian. Later, I published five books with the exquisite Kelsey Street Press, a collective focused on experimental writing by women. Recently, I studied with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, looping back to some of these concerns. Her ideas about the subaltern and her deep commitment to not having closure influenced me.

The magazine Conjunctions, where I was a contributing editor, provided another community of writers in the 1980s: Walter Abish, John Hawkes, Ann Lauterbach, Michael Palmer, Leslie Scalapino, Barbara and Dennis Tedlock.

Other Influences: Your writing itself is very visual with its literal length of the long line and how light and space is held on the page. How have your collaborations with artists inflected your poetry? How did they evolve and what emerged in your writing and thinking that might not have otherwise?

Mei-mei Berssenbrugge: In my twenties I started to look at contemporary art in New York and to listen to contemporary classical music. I studied film history with Andrew Sarris. I felt that new cultural ideas were often expressed in other arts before appearing in literature, such as abstraction, feminism, appropriation, and postmodernism, and that I could transfer these ideas more easily from another discipline into writing. I looked to Luciano Berio, John Cage, Ornette Coleman, Merce Cunningham, Marguerite Duras, Arnold Schoenberg, Jean-Luc Godard, Akira Kurosawa, Tashi Quartet, The Living Theatre, Anton Webern, Robert Wilson.

It wasn’t until I started collaborating that I made strong ties with visual artists. I lived alone in rural northern New Mexico, and collaboration was a way for me to socialize, expand my vision, and visit New York. When I start a collaboration, I try to learn about an artist by using their work, our conversations, our intentions, and I create an imaginary space between us for the artist to move into. If I generate the text first, I open out the density of my text to make space for the other person’s use. If the artist generates the work first, I write into this space between us. I met my husband Richard Tuttle in 1987 collaborating on Hiddenness, an artist’s book for the Whitney Museum of Art, and we’ve done several collaborations since. The latest is at the Kunstverein, Munich, where I read my poem, “Hello, the Roses,” which he uses as a choreographic score for installing his works. Richard introduced me to Kiki Smith, with whom I’ve made many artist’s books. I’ve also collaborated with the choreographer Blondell Cummings, the composer Tan Dun, and the theater director Shi Zheng Chen, and others.

When Kiki Smith and I embarked on our first collaboration, Endocrinology, we had the intention of bringing light into our internal organs, maybe to lighten heavy emotions. She was bringing images of the body back into contemporary art and told me about the medical bookstore at Barnes & Noble. I wrote a long, loose work about the endocrine system, and she made prints of endocrine organs on Nepalese paper that was translucent, so one could see the image on the page behind, the way organs are layered in our bodies. Kiki made more images than I had text, so I separated my stanzas into sentences to extend the text. Since then, I’ve used this sentence stanza as the basic building block for my poems.

I had worked for Georgia O’Keeffe in Abiquiú, New Mexico, in the 1980s, but after I met Richard, I came to know many artists. The most influential, after Richard, was Agnes Martin, whom he had known since he was a student. For a few years, we all lived in Galisteo, New Mexico, and we often ate together and visited her studio. Bruce Nauman and Susan Rothenberg were part of this community. I still learn every day from Martin’s painting, from her sensitivity and courage, her joy, her suffering transmuted into beauty.

Other Influences: Can you tell us how you study and collaborate with landscape, the light and how it reaches the page? In thinking of this, you have also reached into areas that are not always considered “poetic,” such as your study of science and your conversations with farmers.

Mei-mei Berssenbrugge: I think of the landscape as visual and experiential across time, which may be the opposite of abstract. I’ve lived in rural New Mexico for almost fifty years, and I’ve used place as a kind of structural matrix for my poems. The arc of sun across a wide horizon may have generated my long line, and it gave me range, physical extension. I read widely in Indigenous cosmologies. Through Leslie Silko, I began to see the timeless entwinement of peoples and places.

For about twenty years, there has not been enough rain on our mesa, and we started to spend summers in a cabin on the Maine coast. The green of Maine woods became an emblem for me. I researched ideas of ecology and wrote about plants, animals, and weather in Hello, the Roses. It became difficult to separate landscape from climate change. Recently, I’ve returned to plants as my subject—plants in a matrix of earth and beyond, and as higher beings with fractal mysteries of growth, nurture, love, and vitality.

Other Influences: Your latest book, A Treatise on Stars, seems to dialogue with the stars literally. How do constellations and astronomy resonate with your writing? Also, over the years, some readers have responded to aspects of your work as meditative or spiritual. Is there a certain spiritualism that has informed your work over the years?

Mei-mei Berssenbrugge: I began to seek larger systems of balance and wholeness, and these larger systems naturally extend to the stars. Combining intellectual systems with the spiritual and with “place” has been my method of composition. I consider quantum physics an intellectual system, like deconstruction or Tibetan Buddhism, and there are marvelous correlations between ideas of quantum mechanics and New Age philosophies. When I started writing A Treatise on Stars, I wanted to express one unified ecosystem between our earth and the heavens. Many Indigenous cultures believed in travel between these realms. I read books about star cultures in North and South America. I read many lay books on quantum physics and books that applied quantum theory to consciousness, evolution, and ecology. Years ago, I found a book called Vibrational Medicine by Richard Gerber, published by Bear & Co., and I’ve since read many Bear & Co. books, including texts channeled from the Pleiades. The Pleiadean Beings are important to many cultures in Peru, especially in Chavín de Huántar where I traveled with Richard in 2016. Throughout Stars, I was seeking a connectedness in all things through consciousness that would illuminate our heavy contemporary experience. I sought to ease my grief about earth’s degradation, which was becoming an unhealthy obsession. I feel there’s a mystical equation between unity or connectedness and love, and that is what I was trying to suggest with Stars.

Excerpted from Other Influences: An Untold History of Feminist Avant-Garde Poetry edited by Marcella Durand and Jennifer Firestone. Reprinted with permission from The MIT Press. Copyright 2024.