Interviews

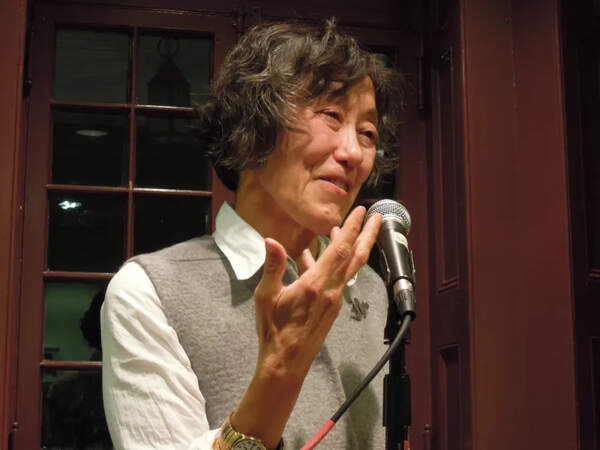

An Interview with Rae Armantrout

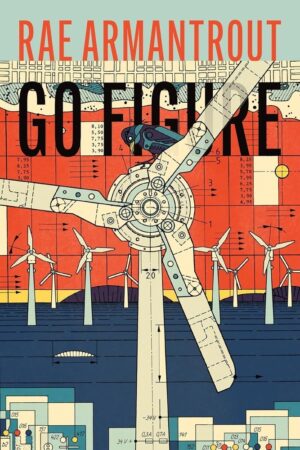

Rae Armantrout's twentieth full-length collection, Go Figure, probes being in time with finely tuned humor and sensitivity. In it, the poet fully commands her wheelhouse, sequencing witty, energetic poems investigating the environment, theoretical physics, family dynamics, and cosmogony. Blending sharply defined imagery and slant philosophical musings, Go Figure is a voice-driven tour-de-force that sews meadows of emotional insight on a shifting ground of intellectual inquiry. In the following interview, conducted by email in August, 2024, she discusses the power and pitfalls of description, her interest in doubling, how she draws inspiration from light, and her own education in poetry.

Parker Menzimer: Unlike your last collection, Finalists, which contains two major books written before and during the pandemic, Go Figure is a unified collection with no part dividers. Can you speak to what inspired it and how you wrote it?

Rae Armantrout: All of my books are really written poem by poem and then arranged into what I think is the best order. I know that sounds dull. I guess there’s a bit more to it than that. When I see that something has come up several times, I will lean into it, take it further. For instance, in Go Figure, I started to notice titles—and poems—that had to do with forward motion. The poem “Go Figure,” which became the title poem, is one. Then there’s “Here I Go.” I had those pretty early. I think others like “Go Round,” “Traveling,” “Further Thought,” “Forth,” “Escape Velocity,” “Skid,” etc. came later. How much of that is deliberate and how much just happened I’m not sure. Not to overwork a metaphor, but the idea of hurtling forward, for better or worse, gained momentum as I went on.

Of course, there are subtle (or not-so-subtle) changes in what I’m seeing and experiencing as time passes. My poems are open to whatever is going on around me. These days, it takes me two to two-and-a-half years to write a book. This book was written between 2021 and 2023. One major fact of life in the West was and is fire. One smokey day a couple of years ago, for instance, when I was alone and without a car, an emergency message came over my phone saying, “Evacuate immediately...!” I went outside and looked around. I didn’t see flames, but I was still quite worried. I knew there was a fire on the western slope of the Cascade Mountains, which isn’t that far from where I live. I didn’t see neighbors on the street. They were probably at work. After about ten minutes, another emergency message came on saying the first had been a mistake. “Oops, we didn’t mean Everett.” The poems “Simply,” “Flame,” “Reconnaissance,” “Reporting,” “Traveling,” and, naturally, “Fire” respond in some way to the existence of fire. I could go on, but you get the idea.

PM: The poems in Go Figure contend with planetary health, the possibility that our planet will someday be unable to support human life. Are you an eco-pessimist? How else does your thinking about climate influence your poetry? I am thinking of a stanza from “Here I Go” in which you write:

There’s no way to explain

how faultlessly I want to write

about how pointless all this is.

In part three of that poem you write: “But I am hard to discourage.”

RA: Well, as a species we’re hard to discourage, right? For better or worse. Plus I am a part-time caretaker for my granddaughters, now seven years old. Like all young children, they are so alive, so ready to love. It’s hard to look into a child’s eyes and be an eco-pessimist. Rationally though, when I see the inability of governments, politicians, and industry to see past their stock prices or their polling, when I see the willed ignorance and xenophobia, it’s hard to have much hope for our species. The end of “Here I Go” is a zany escape fantasy, flying off on orchid “light-sails”—which aren’t sails at all.

PM: You have spoken in interviews about the principle of collage in your poetry. On a practical level, I am curious about how you collect the language you include in your poems. Do you keep a notebook where you record found language, observations, dialogue, etc.?

RA: Yes. I want my poems to be responsive, permeable. When something seems to just present itself to me—whether a striking sight or an image in a dream, I have to take note. There’s something thrilling about a thing that comes to you spontaneously as if from somewhere else. For me that “somewhere else” doesn’t have to be the Martians in my radio (though it could be), it could also be what the crows are doing out in the street. I don’t want the poem to be just me. I don’t think top-down planning works—or at least it has limited possibilities. I want to leave room for the unexpected. That means the poem can veer in various directions. Sometimes that “works,” sometimes not. I don’t use everything I put down in a notebook.

PM: Some of the material that makes it into your poetry is slice-of-life observations: fragments about your twin granddaughters, for example. You have also published memoirs (I’m thinking of True) and I’ve read you’re working on a more extensive memoir. What material do you reference when you’re working on memoiristic work? Do you keep a diary, archives of your correspondences, things like that?

RA: I started extending my little memoir True, during the lockdown phase of the pandemic. True ends when I’m twenty-three. My idea was to fill in some things I’d left out and then extend it in time—all the way to the present, if possible. I planned to keep it private. Two years ago, I sent the first forty pages of it to the Stanford library with instructions that it can only be shown to scholars and only with my permission—which I have given once so far. I did it this way partly because I was going to write about living friends and acquaintances, some of whom are well known in the poetry world. And partly because I was going to get into some painful stuff and I didn’t want to be inhibited. Unfortunately, I haven’t kept it up. I find it extremely boring to write about my past. I know that what I remember is quite partial in both senses of the word. Actually, I have never been able to keep a diary either. My life just doesn’t interest me that much. What interests me is the way one thing intersects with another, how they speak to each other when they’re juxtaposed. I like to put the macro alongside the micro, for instance. In “In Practice,” a physical law regarding the way heat moves as it dissipates is juxtaposed with the urgent (heated) demands of a child who wants to wear “the kitty tail right now.” The part about the kitty tail is one of those “slice of life” moments you mention. My granddaughters did have a fight about who was going to get to wear part of a Halloween cat costume. but that would have limited interest by itself. I was also reading The Order of Time by Carlo Rovelli. I wanted to bring in the child’s voice to disrupt the necessarily cool depiction of time and space in physics. That said, I should get back to the memoir. Yesterday I wrote a couple of new pages. I’m up to (you’ll laugh) 1975 when I’d been in San Francisco for three years and the Language poetry thing was starting to take off. I don’t imagine I’ll ever manage to bring the text into this century.

PM: Go Figure contains so many wonderfully crafted, economical images of plants and flowers. For example, from “Escape Velocity,”:

Out the window, lilac’s

lavender swag

above long leaves

split down the middle

or from “Uncanny Valleys,”:

A sleek leaf,

tapered like a blade,

hoisted like a sail—

of its own accord—

is going no place

Or from “At the Moment”:

Sun still

on

the wisteria.

The question is

how still.

This tendency isn’t new in your poetry, but flowers and plants seem especially foregrounded in Go Figure. Can you speak to your interest in describing nature?

RA:

You’re right. I just love the shapes and colors of plants and they do tend to get into my poems. Now that I live in the Pacific Northwest, I am responding to a different landscape. There used to be a lot of palm trees in my poems. Now not so much. “Description” has a bad rep in some quarters. (I, too, dislike it—sometimes at least) It can be tiresome. I tend to use the word “depiction” Is that different? I don’t know. I’ve been fascinated by all the new (new to me) species of trees and flowers here. I find nothing more beautiful than the play of light on leaves, the glimmers and shadows. I’m addicted to beauty and I’m not ashamed of it. Plants are what we have to lose most immediately and obviously, in relentless heat waves and fires. I’m not sure why I focus more on plants than on animals—maybe because they stay put. They’re always right there when I look up.

PM:

In an interview with David Moscovich for Rain Taxi, you share that the first poem you ever wrote, in first or second grade, was this: “The little fisheys swim / around and around / and away.” It does not surprise me that your first poem was about fish swimming in circles before disappearing to some unknown place—a simple description in short lines infused with a subtly comic sense of futility and agnosticism. It also does not surprise me that you describe this poem, in that same interview, as being indebted to haiku. Can you speak about any ongoing influence haiku has had on your work?

RA:

I can’t actually remember whether my primary grade teacher introduced me to haiku. It would help explain that poem. I do know that I read a book on Zen as an undergraduate which exposed me to Basho and Issa. I was really drawn to those poets. I think you can see a bit of haiku and also Zen in a poem like “Hey” in Versed. It goes:

Hey

Sound

may be addressed

to you

or it may not.

*

A receipt

blown crazily

across a parking lot,

was, perhaps,

a moth.

Confusing a dead leaf with a butterfly is a trope in at least one famous haiku. Don’t ask me which now. The second part of “Hey” does a turn on that, conflating a flying receipt and a moth. It’s less “natural” than the haiku, but it’s still a moment of possible levity in both. The “sound” in the first section is the title word “hey,” which I heard someone yell—presumably not at me but who knows—as I left the store. The first part questions whether and how something was intended; the second part asks whether a thing is animate—if it’s flying intentionally.

PM:

In Go Figure you investigate your interest in cosmogony and, as in your previous books, deploy references to theoretical physics as well as biblical creation stories. I was especially struck by the many references to light in these poems, for example, in “Traveling”:

Light “propagates”

(as in propaganda?),

meaning it clones itself

to travel

RA: Right, light and cosmology have shown up a lot in my work from the very start. The first poem in my first book, Extremities, talks about the “glitter of edges.”

Light is the first thing God creates in Genesis and, according to near-death-experience accounts, it’s common to see a light and some sort of tunnel when you’re dying—so light is Alpha and Omega. When I read either creation myths or cosmology, I’m usually full of nagging questions. I like to bring those questions into the poem somehow. One fascinating thing about light is that, according to Einstein, it’s the one thing in the universe that isn’t relative. It’s a universal speed limit. Nothing can go faster than light. Everyone knows that, of course. It travels three-hundred-thousand kilometers a second in a vacuum regardless of the observer’s location or motion. That’s pretty peculiar when you think about it. The speed of any other object is relative to how fast you’re moving (everything is moving) and in which direction when you make the measurement.

In the quote from “Traveling,” I was interested in the use of the word “propagate.” Light is said to be “self-propagating.” I certainly can’t explain what that means in physics, but I like the associations. Life is self-propagating too. Light’s propagation suggests it doesn’t really travel at all; it continually recreates itself instead. I’m sticking with that until some physicist tells me I’m wrong.

PM:

Twins and doubles are everywhere in Go Figure, from mentions of your twin granddaughters to descriptions of leaves split down the middle. The child psychologist Dorothy Burlingham has described the “fantasy of possessing a twin” as a “common daydream…which in spite of its frequency has received very little attention.” Can you speak to your interest in the figure of the twin?

RA:

Actually, my interest in doubling started well before my granddaughters were born. I’m happy you noticed. I don’t really know what accounts for it. Bilateral symmetry is very common in nature. We see it in everything from humans to the birds and the bees, right? It’s common in plants too. Symmetry and symmetry breaking are important in cosmology. Antimatter is the mirror image of ordinary matter. It has an opposite change. It’s created in energetic cosmic ray collisions and in Beta decay—but there isn’t very much of it around, fortunately since matter and antimatter destroy one another on contact. We could think of it as our evil twin. Never mind, let’s not go there. I’ve read that the universe was created in a moment of symmetry breaking. The big bang should have created an equal amount of matter and antimatter which would have meant the universe had a very short life. (How scientists know what the big bang “should” have done, I have no idea.) Anyway, mysteriously, the antimatter disappeared (for the most part) and here we are. Now that’s really interesting. It’s like that phenomenon where one twin absorbs the other in the womb. I have a new poem called “Ledger” about this (it will be published by the Poetry Review in England). One reason I’m fascinated by doubles is that, in a way, consciousness is a kind of doubling. When we see ourselves (mentally), we’ve created a double, an observer who comments on what we experience. I have the sense that there is something fundamental about the double.

PM:

Speaking of doubling, I’m interested in something you said in a 2019 interview with Brian Reed for the Paris Review. You stated that “‘She’ is often the speaker in poetry, right? ‘She’ or ‘he’ or ‘you.’ I mean, they’re often veils for ‘I.’” You went on to say, “Actually, I don’t use ‘she’ much that way anymore.” But halfway through Go Figure, after the poem “Seeing Reason,” where “She had switched / into the third person,” the third person begins cropping up. I’m thinking of later poems like “Reverb” where:

She wrote this down

because she recognized

it

as a thought—the kind she liked. Or used to like. One with depth,

with reverb.

The third person here, and its relationship to “reverb,” seems related to your interest in the figure of the twin. What else is the third person doing in Go Figure?

RA:

The first thing I notice when I start thumbing through the book is how often I use the first person—at least in comparison to my earlier work. It’s first person in four of the first five poems: “Here I Go,” “It,” “Skid,” Fortune.” I’ve been challenging myself to use first person more often. I do, of course, use third person in “Seeing Reason” which is very much about me as a writer. Maybe that felt too close to home and I needed a little distance. It takes distance to create “reverb,” (A reverberation or echo is, of course, a kind of double). The speaker in my poems isn’t exactly me—especially in my first-person poems! Well, sometimes it is, but a lot of times it isn’t. I often borrow an authority I know to be questionable when I write. For instance, I might tell you how the universe began as if I had been right there, when really, how would I know anything about that. My first person speculates more often than it confesses. It takes on roles. People, even friends, don’t always get that. I have one new poem that makes up the functions of the organs in the fanciful way that medieval doctors did. It ends by saying:

The heart is the organ

of self-harm.

it beats itself

against cage bars

from a natural love

of syncopation.

I showed this to a friend, and he said he didn’t agree with my statement at the end. I said “Neither do I!” Not literally. I mean, medically, it’s crazy. I also said that the liver is the organ of “qualms.” The speaker in the poem is saying these things. Maybe that sounds like a “cop-out.” But poems come to me, often, in and with voices. Voices enable them, if you will. You mention how the poem “Seeing Reason” uses “she.” In that poem, I’m speaking directly to the reader. I needed to take a step back to do it. I’m talking about this very subject:

She might have to retire her banshee voice,

her campy, scary voice

(In fact, I haven’t actually retired it yet.) My thought was that when there’s a fire down the block or a thousand-year flood every other year, you don’t need to use a witchy-sounding voice to make it scary. It just is. You just need to run.

PM: Some years ago, I took down this line from your poem “Up To Speed”: “Vagueness is personal!” Can you elaborate on how that might be?

RA:

Hmm. That’s a hard one. I’m looking at that poem now. The line you quote is the first line of the third section of the poem. I think (I hope) the line is meaningful to the extent that it is in association with the lines that come before or after it. The section before it references (believe it or not) the eccentric, personal way kitchens (my mother’s, if you want to know) are organized. (This goes here and that goes there, no ifs, ands, or buts.)

Is it such agendas?

which survive

as souls?

*

Vagueness is personal!

A wall of concrete bricks,

right there

while sun surveys its grooves

If I had to say something about this—which I guess I do—I might say that it was funny/sad to imagine something like cabinet allocation or, say, a to-do list floating around as a ghost. “Vagueness is personal!” stakes out some kind of undefined personal space between that organizational tendency and the flat concrete wall. I mean the line is rather vague frankly. It sounds a bit desperate, but I guess I don’t mind that. What really strikes me now is the end of that section, which goes:

Light is “with God”

(light, the traveler).

That so recalls our discussion about “light” in my poems. “Light” here replaces “The Word” in the famous verse from the gospel of John (I think) which says, “And the Word was with God; and the Word was God.” Here light is with God and, if you follow John’s logic is God. It is the nature of light to keep moving, to “travel” or maybe “propagate” itself so that’s it’s here and gone at the same time….