Interviews

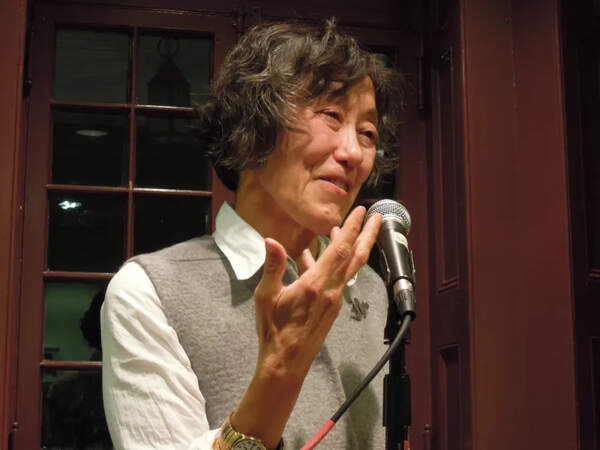

Questions of Faith: Meena Alexander

"Questions of Faith" is a selection of excerpts from interviews that Dianne Bilyak has conducted over the past decade. The interviews began as her master's thesis for The Institute of Sacred Music & Arts at Yale Divinity School. The poets were queried about their religious upbringing, current practices, and how these may or may not have influenced their writing, as well as general questions related to faith, doubt, and meaning, and more specific questions related to each poet's work.

* * *

Dianne Bilyak: What was the role of organized religion in your childhood?

Meena Alexander: Dianne, organized religion was of very great importance, it was also a zone of real conflict for me. As a teenager I used to think of Blake's line in the poem "Garden of Love": "Thou shalt not writ over the door." As a woman I felt I was barred from my own body in some terrible way by the edicts of the religion I grew up in. At the same time I felt the enormous richness of the Biblical tradition and emotions vested in it. The story of Isaac haunted me, the sacrifice of the child—what Abraham was willing to do. I remember hearing the story in church when I was little; it pierced me to the quick.

I was born into a Syrian Christian family in India. We come from Kerala on the south west coast. There are churches there of the Eastern rite, predating Western Christianity. The Mass till 300 years ago used to be Syriac. There are still passages that are sung in Syriac; beautiful old liturgies you can still hear in the Orthodox churches of Greece or the Coptic churches of Egypt. My mother's family was particularly close to the church hierarchy and my maternal grandfather, who was a powerful figure in my childhood, was a theologian.

Then there was Hinduism all around; in India and later when I went to Sudan, Islam. I was very moved by the idea of the god of love, Krishna, and it seemed closer to what I wanted than Jesus who hung on the cross. But the religion of my childhood, Christianity, still takes my breath away. Perhaps what I long for is a spirituality that is freed from caste and creed. What did Roethke say somewhere, "A house for wisdom, a field for revelation"? Always for me a field, rather than the closed church. I also love the medieval mystics—Juliana of Norwich for instance. "I am the ground," she said, "of Thy Beseeching." As a teenager I pondered that.

DB: What role does it play for you as an adult?

MA: My husband is Jewish and my late father-in-law was a rabbi, so now, there is a way in which my separation from Christianity is more clear. I still dream though of being a believer some day, entering a church and finding that I can pray. In times of crisis I do turn to the prayers of my childhood.

DB: In what ways, if any, did or does this influence your writing?

MA: Dianne, this is a very hard question. I have no doubt that my religious upbringing and my turning away from it have been absolutely crucial to my writing. Not just turning away from organized religion but seeking out other sources of spirituality. In my poems you will find elements of Hinduism and Buddhism. I recently spent a month in East Jerusalem and the West Bank. My time in Jerusalem consisted of living in the walled city just inside Herod's gate in the twelfth century Indian hospice and then in a home on Chain Street where my windows opened onto the esplanade of the Wailing Wall and across that wall was Al Aqsa mosque. And beyond the ancient buildings, hidden from sight, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. There is so much desire for sanctity in that city and so much separation—the great music of human prayers, in that city of golden stone. I am writing some poems about the experience. One is called "Impossible Grace" and has come out in TriQuarterly Online. I have others forthcoming in Kenyon Review, KR Online, and also Guernica. It seems to me that we have religion so that can try to make sense of human suffering. Why then is religion such a site of terrible human conflict?

DB: Tell me about your time as an Elector of the American Poet's Corner at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. How did that come about and what were some of the things you did?

MA: We used to live near the Cathedral in my early years in the city and out of the high window of our apartment on 113 Street I could see the rose window with its blue stained glass. Even in those days I used to go and stand in front of the American Poets Corner, which seemed a most mysterious place to me. I had no idea how the poets were chosen and many years later when I was invited to be an Elector, I felt it was a great honor. Each Elector is there for five years and together the electors decide on the poet who will be inducted into that very special place—we also decide which lines to choose to inscribe on stone. It was deeply moving when Phillis Wheatley was chosen. It was a time for me to spend reading her work and thinking about her. I composed a few lines in her memory, a poem that I read at the celebration for her.

DB: I read in one interview that you studied phenomenology. In what ways did this type of philosophy influence your writing or approach to writing?

MA: I was just 18 when I went from a third world country (Sudan) to England and plunged into work for a Ph.D. I was interested in time, memory, and the body and reading Husserl gave me a way into the mysteries of internal time consciousness. I think it was the notion that we make our world, in as much as we inhere in it, that gripped me—what Wordsworth called the "mighty world of eye and ear / both what we half create and what perceive." But where Husserl fell into idealism of a sort (however hard he tried—the object as intended by consciousness), Merleau-Ponty, whose work I loved, turned to the body, the corps vecu. To Merleau-Ponty, the body in the world allowed us a way to make sense of the sensorium and the way things cohere for us. In hindsight I feel it was really my bewilderment at the terrible forces of history—going from the turbulence of India and Sudan, to the England of the 70s that made me hold onto this way of thinking—a kind of mental shield. I was also much taken by Wallace Stevens and read his poems over and over. Perhaps that also allowed me to escape from my own body.

DB: You've traveled so widely among different cultures, what are some of the particular ways you have seen religion and poetry intersecting? Does it seem like a more natural pairing in some cultures and do you have any thoughts on why?

MA: Yes, it does seem like a more natural pairing in India for instance, more so than in the United States, along with an instinct for the great circling life that is outside us and in us too (of course for the native peoples of America, the land itself was instinct with spirit—and this is so powerful). I could walk by a stone in the town where I was born and that stone or a tree would be worshipped as a site of divinity. Poetry surely partakes of this and there is an ancient tradition in India that allows for this, however much one's work may be part of a Modernist or even Postmodernist field. So words exist in a different air. I should say though that there are certain rocks in Central Park to which I keep returning, and rocks in Fort Tryon park, right where I live, the great ancient boulders of granite and schist that make this island what it is.

I don't know if I have spoken of this before but I am deeply moved by the poetry of the medieval mystic Mirabai, a princess who left her kingdom and wandered over so many borders, singing praises of her beloved Krishna. Ishtadevata—the god who one desires, the god formed in the image of desire—also makes great sense to me. The borders of the visible are always lit by the light of what we cannot see, the great world of spirit that shines for us. Religions try to put words there, so do poems.

* * *

Meena Alexander is the author of six books of poems, most recently Quickly Changing River (TriQuarterly Books, 2008). Her book of essays Poetics of Dislocation is published by the University of Michigan Poets on Poetry Series, 2009. She is the editor of Indian Love Poems (Everyman's Library, 2005). She teaches at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York.

Dianne Bilyak has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and her first book of poems,Against the Turning, will be released in September 2011. Through the Institute of Sacred Music at Yale Divinity School, she received a graduate degree in religion and literature. She has been interviewing poets for several years and editing the transcripts for inclusion in a manuscript called Poetic Faith. Please visit her website.