In Their Own Words

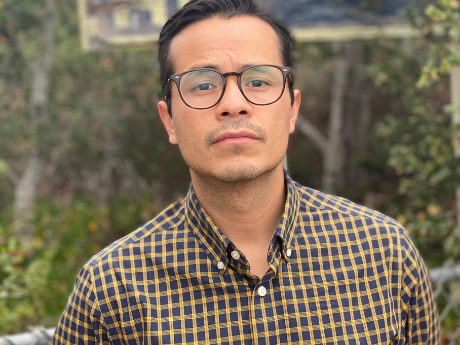

Nathan Xavier Osorio on “English as a Second Language”

Surrendering to nausea in the felt-lined Tijuana-bound camper

I doubted the integrity of the breast-shaped nuclear reactors

fixed on the Pacific shore, cherry-pink nipples upright and beaconing

at a waltz tempo to the deepwater roughnecks swaying in their hemp

hammocks below a network of oil lines spouting flames into the oceanic

infinitude dyed dead-eagle-god red and I shrinking in importance

like in my collegiate days when I nodded submissively to a professor

who assured me my failure was because English was my second language

which is true if second to the cosmic mutterings of black holes

which is true nights I bellow desert monsoons into extinction

which is true when my hands are held up bearing the Atlantean

burden of brownness but which is most true here, surrendering

to nausea in the felt-lined Tijuana-bound camper

piloted by my dark-skinned father whom I’ve only ever understood in dialect

amalgamated from epazote and McDonald’s fries gathered

between the San Gabriel Mountains and Popocatepetl

who continues his delicate lament of ash even when exposed

by the melting glaciers that once kept his mourning summit numb

I whisper to the Exxon™ Mobil gas station that I too can love

enough to become a volcano and reach out so that my palm

skates atop a gust of sea breeze and the invisible exhaust

of topless convertibles, blond hair pouring upward

from their front seats and strangling the open air uninhibited

and drunken with the riches of the west, the tall straw rippling

on the hillside in unison, the mega-outlet with its 24-hour security

desk illuminating the alleyways of the bad neighborhood

and the hordes of day laborers spilling out into the avenues

climbing atop trucks unsolicited, sharp-eyed and hungry

now I will say it, blessed be the Virgin Mary

that I’ve kept this close to the southern frontier

this close to the police beat and the ticking tear-gas canisters,

this close to the unidentifiable pots of spices roiling in the night markets

I reach to Gloria Anzaldúa and read Borderlands

till I lose sight of the swallows’ nests that stipple the cliffsides

and drift onto the Harbor Freeway where in March 2006

the children of the frontier were in multitudes curdling traffic

a thousand strong as I sat sugar-buzzed and unobstructive in homeroom

and now my head rolls forward and I startle awake

the idle nuclear reactors pulsing longingly in the rearview mirror

the oil-rig plume billowing tenderly in response, our roughnecks’

night sweat cooled by the prospect of tomorrow’s new depths

it baited as progress as self-preservation that will not include me

or my pilot or maybe even you, but whoever has and still sits

in the enormous leather chair.

Reprinted from The Last Town Before The Mojave (Poetry Society of America, 2022). All rights reserved.

On “English as a Second Language”

Growing up, my father would drive us down to Tijuana and Puerto Nuevo in Baja California, Mexico for a weekend getaway and cheap prescription medicine. The four-hour drive on the 5 freeway takes you through the length of Los Angeles, Orange County, and San Diego before depositing you at the San Ysidro Port of Entry, the U.S.’s busiest land border crossing. The drive, which I try to capture in my poem as a mutation of the classic American Road Trip, is a remarkable display of U.S. imperialism and racial inequity.

This stretch of the 5 freeway takes you through influential media capitals, neighborhoods of Latin American diasporas, and along the now-decommissioned San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station, which embraces the Pacific coastline as a monument to failed American ingenuity. This is all before arriving to San Diego, the birthplace of colonial California, home to one of the world’s largest imperial naval fleets, and the first American stop for generations of migrants displaced by U.S. interference—including both of my parents. This highway and its eclectic landscapes are embedded, like my poem, with memories of my personal coming-of-age and familial history, but also the long struggle for the freedom of movement.

I’m drawn to using the lyric to better understand the material detritus of late-stage capitalism and its very real human cost. I originally wrote the poem in response to a prompt from the poet Timothy Donnelly, based on Ross Gay’s “Ode to Sleeping in my clothes.” Although no longer an ode in the traditional sense, my poem examines the colossus infrastructures that sustain American enterprise by any means necessary—and the estrangement experienced by those who are exploited in its service. I hope my poem does this by enacting a parallel formal architecture on the page: a rhythmic system built on maximalist images, an insurgent ode to a more critical—and hopefully liberated—relationship to the English Langauge.