New American Poets

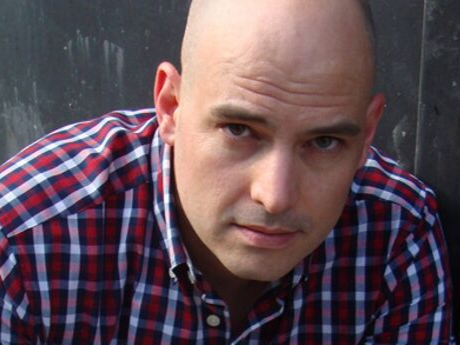

New American Poets: Timothy Donnelly

Her Palm, Her Apotheosis

There—past the ghost of the carpet,

an inch from the tasseled fringe, an inch

from the froth of the wave

that plashed expressly

west of Asia; here—

in her isolate room,

in a permanent

pot of terra cotta, its imperial fronds

outstretched, unfurled

in a fanning of afternoon sun, this is absolutely

the absolute palm. She sees

nothing else, no one else sees

the palm that she becomes, being

in a fanfare of vanishing, sun.

From Twenty-seven Props for a Production of Eine Lebenszeit (Grove Press, 2003). Copyright 2003 by Timothy Donnelly. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

As a child I found it difficult to fall asleep. I couldn't put an end to the saying of things. More obedient by day, the current of inwardly articulated thoughts—or half-verbalized, half-felt imaginings—only amplified its whirring in the solitude and silence of the night, increasing its insistence, muscling its rhythm to an almost hypnotic hold. Barbara Herrnstein-Smith claims that all of us are "almost continuously" addressing "that most intimate, congenial and attentive listener whom we carry within our own skins." I assume she's right; at any rate, this has been my experience for as long as I can remember, and as a child—unschooled in the stilling of the mind—the unstoppable, exuberant flow of "interior speech" held for me as much interest and fascination as the realm of ordinary objects and sensible people.

Habit asks that I oppose the "interior" and "exterior" realms, but I won't. All thinking is made possible by the material world. Yet our perception and evaluation of that world is, of course, determined by our thinking, determined by our language, and that condition of language which seems to me to hint at the fullest possibility of what it might mean to be, that seems most capable of expressing what Wittgenstein calls "the miracle of the existence of the world," is poetry.

When I began reading poetry in earnest, the poems that mattered to me most were those that generated, to my mind, the same kind of excitement and propulsion that kept me awake as a child; poems that exhibited what I felt to be the power residing in the imagined heart of words, that reveled in the wonder of them beating there to begin with. Poems like "Ode to a Nightingale," "Sunday Morning," and "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock"—poems that presented speakers in readily identifiable dramatic situations, scenarios that served as verbal terra firma from which sudden torrents of aspiring, 'full-throated' and gorgeous utterance sprang. Keats, Stevens, and Eliot were my necessary models. Their influence was perhaps too apparent, or more likely, I mishandled it; in any case, my poems were criticized for being too literary, too artificial, too unreasonable; too gaudy, ambitious, pretentious, strange. ("That's not how people speak," I remember being told.) I was prescribed Robert Lowell and Theodore Roethke. (They didn't take.) I was asked to write from experience, as if I hadn't already.

When I write, what I want is to remember what it felt like beforehand, that early reluctance to relinquish consciousness, that thrilling immersion in an aliveness to language that kept me keeping awake. I want to do justice to the joy and the fright and the wonder of living in language, and to experience as fully as I can what it might mean to be here.

As a child, I couldn't put an end to the saying of things, and as an adult, I refuse to.