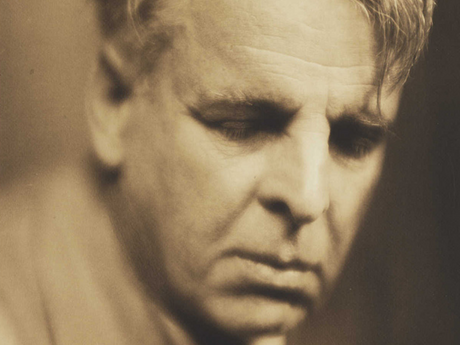

Tributes

Eavan Boland on W. B. Yeats

I remember buying my first copy of Yeats' Collected Poems when I was fifteen. I took the bus one empty September weekend from Killiney, in Dublin, where I was in boarding school, and went into the bookshop which is now Waterstone's bookstore, but then was the old Hodges Figgis, with its airy interiors and round tables piled with magazines. I wasn't a particularly bookish teenager. And so I remember the long bus journey—the sight of the coast when I was leaving and returning, the bracelet of lights in the distance towards Bray—much better than why I went to buy the book. But I did buy it. And went back to school clutching the handsome burgundy hardback with its cream milled covers. And read it. And read it.

But why? I certainly wasn't his inevitable reader. I was hardly more than a stranded teenager, home from London and New York, back in Ireland after years away at the supremely inconvenient moment of fourteen years of age: Unable to name the country I came from. Unable to come from it until I could name it. I felt awkward—an impostor, waiting for my differences and mistakes to be noticed. And so what was it that made me connect so easily, obstinately, powerfully with this finished and magisterial poet who belonged so totally to his country that he felt free to invent it? What is it that makes me connect to this day, across decades, more knowledge and suspicion and under-standing than I had then? Yeats has been the poet I have loved most, have understood most, have returned to most often. And the return is not enacted by going to my shelves and taking down that book with its childish inscription. It is a return made up of the continuous, shiny breakages of memory, of lines and melodies that come in and out of my mind and memory.

The Collected Poems I read is still very much the standard version of Yeats' work. It is arranged chronologically. It goes from the first clipped-off lyrics of his London and Dublin years. And I like to think of him as he describes himself in those years: haunter of libraries and of cranky East End spiritualist meetings. Equally at the edge of The Cheshire Cheese and Grub Street. A young man who, if you had met him in Kensington or on the Strand, might have seemed part fop and part country bumpkin. A young man, however, who went back to a succession of boarding houses and cold rooms and crafted and re-crafted his early poems on a strange frontier between the Pre-Raphaelites and the first stirrings of the Irish revival.

I think for every writer who has been influenced and changed by another one, for every poet who carries another poet with them into their life, there is probably always an epicenter. For me it comes right smack in the middle of the Collected Poems.

The poem is "The Wild Swans at Coole." The poet who wrote it and lived it is not at all the awkward and charming poseur of fin de siecle London. This is an older man—engaged, embittered. He returns in his middle years to the Galway woods, to the late summer twilight, to the freakish, distant white of the swans gathering and making noise. What he makes in turn is a new Irish pastoral: something to put all the easier poetry of place to shame.

I have looked upon these brilliant creatures,

And now my heart is sore.

All's changed since I, hearing at twilight,

The first time on this shore,

The bell-beat of their wings above my head,

Trod with a lighter tread.

Unwearied still, lover by lover,

They paddle in the cold

Companionable streams or climb the air;

Their hearts have not grown old;

Passion or conquest, wander where they will,

Attend upon them still.

Here is the Yeats I first knew. Fiercely musical. Lost in control. It seems impossible that a man and a poet could become more real the more he becomes a master of artifice. But that is precisely what his poems achieved. And in my case, they achieved something to be treasured even more. Here in this gritty twilight, in this disillusioned and complicated series of rhymes and half-rhymes and repeating cadences, I began to hear something different—the sound, at last, of a place where I might no longer be an impostor. A place which could be made exact in language and therefore hospitable to the very degrees of estrangement I felt.

These discoveries, made in reading, can last a lifetime. But they aren't private, of course, and can't be exclusive. In any case, things have changed. The bus in from the coast has shimmered and changed into the Dart. The Saturday traffic is as dense as a Friday afternoon. The buildings are bulkier, the cars sleeker, and the streets more crowded. But someone else is taking down that book from the shelf, even as I write this. Is bringing it back. Will read it after dark. Someone else will carry that exact magic with them forever. As I have. And always will.

Originally published in Crossroads, Fall 1998.