Tributes

James Laughlin, Publisher & Poet

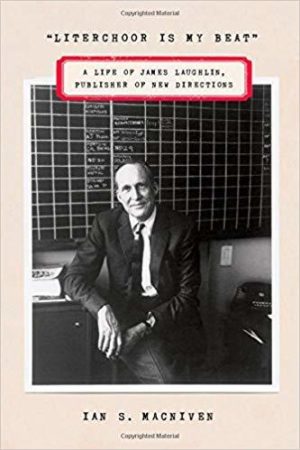

Preface from "Literchoor Is My Beat" A Life of James Laughlin, Publisher of New Directions (FSG, 2014)

Born handsome, brilliant, and rich, all his life James Laughlin courted the art of self-effacement. But even as he practiced disappearance, a behind-the-scenes master rather than a public figure, he, more than any other person of the twentieth century, directed the course of American writing and crested the waves of American passions and preoccupations. His life is mirrored in his friendships and in the careers of the many writers he championed.

Laughlin lived eighty-three years and thirteen days, and he was planning, writing, editing, and publishing until the very end. His importance to American and to world literature has been and will continue to be measured by the authors he published under the New Directions imprint, the firm that he founded in 1936 while he was still a Harvard undergraduate—nurturing authors who in many cases would owe their reputations to his early support. He published almost fifteen hundred books by others and wrote more than thirty of his own: poetry, essays, short stories, translations. He developed the Alta ski area in Utah at the very dawn of skiing in America. He loved India and worked there with the Ford Foundation in various publishing ventures over a five-year period. A mere sentence about his relationship with each of the more than two and a half thousand people he corresponded with, entertained, and skied alongside would fill this volume. "Getting around the world as I have done has been a marvelous experience," he wrote to Thomas Merton, "but you pay for it, in a way, in keeping up with all the contacts that you've made in foreign parts."

This story of a life is perforce selective, focused, and yes, arbitrary. It is also the story of the publishing house Laughlin founded. And it is emblematic rather than exhaustive. My greatest regret on committing this work to the publisher is that so many persons significant to Laughlin's life and to the history of New Directions have been accorded mere passing mention, or even omitted entirely. But I have tried to present a true portrait, with the clear outlines of a remarkable personality, a force in publishing, an original voice in American poetry, a visionary in skiing, and a world traveler of discernment and judgment.

More than anything else, perhaps, Laughlin provided a nexus: he brought writers together. He introduced them to other writers whom they needed for their artistic development. Sometimes it was a personal introduction, as when he sent Charles Olson, who needed a mentor, to Ezra Pound, who needed a friend—Pound, accused of treason, had just been committed to St. Elizabeths Hospital. More often, Laughlin furnished books that served as another kind of introduction—to a literary circle that would become vital to a writer then just starting out: "The first person who introduced me to writing as a craft," said the poet Robert Creeley, "was Ezra Pound," whom Creeley encountered in the New Directions editions of Polite Essays and Guide to Kulchur. Soon Creeley was corresponding with Pound and William Carlos Williams, and he became influenced by others in the extended Laughlin circle: Olson, Robert Duncan, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsberg, Denise Levertov, Kenneth Rexroth, Louis Zukofsky.

Surrounded by an immense and constantly growing cast, Laughlin himself lived beset by crises. The courage, intelligence, and humor with which he confronted each challenge form the dramatic contours of his life story. Early on, he overcame a physical handicap and injuries; later, he was faced with family opposition to his publishing, public condemnation of some of his authors, marital disruption, and financial constraints. All his life he was threatened by the genetic curse of bipolar illness. In the truest sense, he was a self-created personality. And while he remained, throughout, vitally engaged with the cultural, social, and political being of America and beyond, he was at times the most unhappy of men—lonely and yearning, even when he appeared the most fortunate.

When Laughlin included them in the first of his series of fifty-five anthologies of poetry and prose, Ezra Pound, Wallace Stevens, and William Carlos Williams were virtual unknowns, sometimes driven to self-publishing. Fifty years later, these three would frequently be singled out as the greatest American poets of the twentieth century. No less discerning when it came to foreign literature, Laughlin became either the first or one of the earliest American publishers of a long list of world figures that includes Baudelaire, Borges, Céline, Hermann Hesse, García Lorca, Thomas Merton, Henry Miller, Eugenio Montale, Nabokov, Pablo Neruda, Nicanor Parra, Pasternak, Octavio Paz, Raja Rao, Rimbaud, and countless others. Personally involved in steering his publishing company right up until his death, James Laughlin created the New Directions backlist, a tally of largely modern and modernist authors that is unequaled in American publishing. And he was no mere publishing tycoon, sitting comfortably in a posh office and directing others to scout, edit, print, and sell books. He began as a one-man operation: editing text, selecting type fonts and paper, designing covers, negotiating with printers in America and Europe, driving cross-country to cajole bookstores into stocking his titles.

And while Laughlin's early print runs might be tiny—often only 100 to 1,500 copies—gradually his choices would define the course of modernism. All his life he scanned countless journals for new writing and followed through on recommendations from a great many friends. He was engaged with his authors on the most intimate level: he argued over Fascism and anti-Semitism with Pound, and scolded Henry Miller for his obscenity and his pecuniary fecklessness; he was raucously denounced by Kenneth Rexroth for publishing "fairies like Tennessee Williams," and cursed by Edward Dahlberg for printing nearly everyone but himself; he sought advice from paranoiac Delmore Schwartz, bought ballet shoes for Céline's wife, paid Kenneth Patchen's medical bills, went to the morgue to identify Dylan Thomas, helped Nabokov with his lepidopterology, meticulously arranged into the acclaimed Asian Journal the chaos of notes that his friend Merton left behind after his tragic electrocution, dined with Octavio Paz at the Century, and discovered Paul Bowles, Denise Levertov, and John Hawkes.

And he was adventurous physically as well as intellectually. He skied down mountains and broke many bones long before "extreme skiing" had even been named; he climbed up the Matterhorn. When he knew that he would be near trout streams or golf courses, he added fly rods or clubs to his kit; dangled from the end of a lifeline while rock climbing in the Sierras; and punctured a lung scaling a fence to reach a mountain brook.

Born into the wealth of Jones & Laughlin Steel in Pittsburgh, paradoxically Laughlin was forced to run his businesses for decades on tight budgets. The Great Depression still gripped America when he founded New Directions, and Laughlin grew up with habits of thrift. For this reason, there is a fair amount here about dollars and even pennies in sales figures and book advances; in fact, for many years, Laughlin insisted upon writing out each author's royalty check himself, no matter how small. The reader should bear in mind that these figures need adjustment for inflation. Roughly computed, $100 in 1936, when Laughlin founded New Directions, would be worth at least $1,500 in 2014 dollars. At the peak of his publishing career, Laughlin would list his occupation on his tax return as "Investor," and there was truth to this claim: he never took a salary from either his publishing or his skiing ventures, and aside from inheritances, his substantial net worth on his death was owed in part to prudent investment. The more New Directions achieved publishing successes, the less proud Laughlin allowed himself to appear, although he was always pleased when one of his authors sold well.

However, it was as a poet that Laughlin in his youth hoped to triumph. Then he met Ezra Pound. The best-known tale about Laughlin portrays his giving up poetry under the impact of Pound's alleged disapproval. The account that Laughlin told goes like this: After spending some months studying under Ezra at the "Ezuversity," Pound's informal academy in Rapallo, master and pupil conferred:

EP: Jaz, you're never gonna be any good as a poet. Why doncher take up somethin' useful?

JL: What's that, Boss?

EP: Why doncher assassernate Henry Seidel Canby?

JL: I'm not smart enough. I wouldn't get away with it.

EP: You'd better become a publisher. You've prob'ly got enough brains fer that.

Maybe it happened this way. However, the story—a good one that Laughlin relished repeating on the lecture circuit—was told and retold by one of the most self-deprecating yarn-spinners alive, until it became a mythology. And while I like the story very much, I do not believe it, for reasons that I have set down in these pages. And this points to one of the leitmotifs of this volume: the sifting of reality out of the corpus of myth. From time to time I unmask the joker, reveal tricks of the illusionist. That said, I have found that Laughlin was in the main searingly honest, especially in confession. I count it no sin on Laughlin's part if he was occasionally unreliable. He sometimes embroidered not out of malice, but because he was a storyteller in the fine old sense of the word: he loved a good tale, and if he could improve on events by giving them a more dramatic spin, so much the better. Also, he was addicted to a pose of humility, and he often made himself the butt of a joke. He hardly ever invented calumnies about others, although he often did about himself. Sometimes he constructed outcomes from a sentimental need to have episodes turn out the way he wished them to have happened—this is one of his most human and endearing traits.

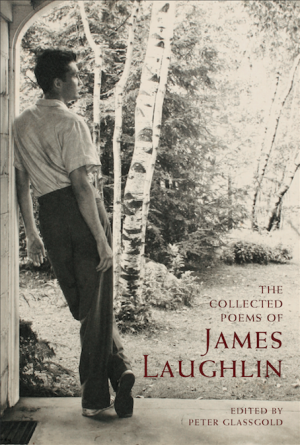

Pound certainly did encourage Laughlin to become a publisher, yet Laughlin continued, by fits and starts, to write poetry throughout his long life. Eventually he blossomed in verse, seeing fifteen volumes of his poems published during his last ten years, and he was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters as a poet. His verse was highly praised by people as varied as Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Guy Davenport, Kenneth Rexroth, and William Carlos Williams. The scholar and author Marjorie Perloff wrote, "Laughlin traces, with the greatest delicacy, grace, and wit, the vagaries of sexual love, the pleasures and pain of memory, the power of literary allusion." He put into his verse those tender and often erotic feelings that his Calvinist reticence forbade him to utter out loud. His best poetry, with a nod toward his master, Catullus, is very fine indeed.

He also wrote hundreds of thousands of letters: missives to authors from Walter Abish to Louis Zukovsky; personal letters to Pound and Jonathan Williams and Tennessee Williams and William Carlos Williams and Henry Miller (an epistolary marathon champion who finally met his match in Laughlin); letters detailing the editing problems of their modernist epic poems or explaining the minutiae of copyright law; letters of gentle rejection ("I have read your manuscript with great admiration, but unfortunately our publishing schedule . . ."); letters of denial to poets wanting to revise poems already in production; letters to his parents, cajoling and scolding them; letters to wives, children, and lovers. To date, seven collections of his exchanges with individual authors—Guy Davenport, Merton, Henry Miller, Pound, Rexroth, Delmore Schwartz, William Carlos Williams—have been published. The year Laughlin died, he did not depart alone among important American literati. As the Dictionary of Literary Biography Yearbook proclaims, "1997 was a year that will be noted for the deaths of four major figures: James Dickey, Allen Ginsberg, Denise Levertov, and the poet-publisher James Laughlin." Each of these was towering in accomplishment, yet more than any other figure of his century, Laughlin's decisions shaped English-language modernist poetry.

My wife, who knew Laughlin professionally and personally during a period of more than twenty years, was visited a few years ago by him in a dream: he asked her how the biography was coming along, and then he said distinctly, "I wanted to be free." He made it clear that he had, stubbornly, always done things the way he wanted to do them. Then he wandered off to clear some vines growing over a window. Of course, if he was often ambiguous and contradictory in life, how far can we credit this voice from the world of dreams? Still, it is pleasant to imagine his ghostly presence.

Once, long after his death, I came upon an old pipe in his office at his residence, Meadow House, the dottle still in the bowl, exuding a faintly lingering scent of tobacco. This is an account of a kind of archaeological dig, the story of a publisher and an angler, of a recluse and an adventurer, of a proselytizer and an idealist, of a connoisseur and a Calvinist and a Buddhist, of a writer of letters and an excellent skier, of a lover and a fine poet. It is the story of a man who lived passionately.

—Ian MacNiven,

Gypsy Hollow, Athens, New York, March 2014

Two Poems by James Laughlin

The Shameful Profession

For years I tried to conceal from the villagers that I wrote poetry

I didn't want them to know that I was an oddball

I didn't want the young men with beards wearing baseball caps

who come to the liquor store in their pickups to buy sixpacks to

know that I was some kind of sissy

I decided it was prudent to buy the Daily News instead of the Times

at the drugstore

I burned my poem drafts at home before I took the trash to the

dump, kids scavenge around there and the old man who does

the recycling is nosey

I took every precaution

But our town is not an easy place to keep secrets, everybody knows

everybody and they gossip when they're getting their mail at the

post office

Things began to come apart

A young man with long hair and a city accent showed up and

asked in the stores where the poet Laughlin lived

Then a pipe burst and the plumber told people that he saw

thousands of books stacked in the cellar, some of them in

foreign languages

Next day the head of the Volunteer Fire Department came,

pretending to check the wiring

I began to get a bit paranoid; the town trooper is supposed to check

each rural road once a week but he came up our road past my

house three days in succession

The axe fell when somehow a reporter for the country paper heard

the rumors and there was a little item: local poet caught

speeding twice on 272, Motor Vehicles may suspend license

Much has changed in my life now

Nobody has laughed at me in the street (I'm over six feet weight 245

and look pretty fit for my age) but they look at me in a funny way

I don't go to Apple House our grocery store any more because a little

girl with her finger in her noise pointed me out to the check-out

lady and asked her something; now I get my liquor and supplies

in the next towns and order Honeybaked Hams from Virginia

by mail

My life is all different now that they know I write poems.

But if they think they can shame me out of it they're very much

mistaken. I'm not breaking any law

I'll go on with it unless they have me declared a public nuisance

and have me sent to the Institute

I've heard there is a poor old fellow in the Institute who claims

he is Henry Wordsworth Longfellow. He'll understand and

be my friend; we can recite to each other if they won't let us

have paper and pencils.

Dylan

One of us had to make the official identification of Dylan's body

at the Medical Examiner's Morgue

Brinnin and I tossed a coin and I lost

It was a crummy building in the hospital complex on First Avenue

and the basement, smelling of formaldehyde, was a confusion

of trolleys with rubber sheets covering bodies

A little old man in a rubber apron was in charge

He put on his glasses to read the name I had written on a slip

of paper and looked around, trying to remember

He lifted on sheet. "Is this him?" It wasn't

Two or three more who weren't "old Messy" of the pubs of SoHo

and Chelsea

Finally we found him and he looked awful, all bloated

"Insult to the brain" was what it said on the autopsy report, too

much booze for too many years

The old man sent me to a window to confirm the identification

where there was a little girl about five feet high, struggling with

the forms, using a pencil stub

She got me to write "Dylan" for her on the form because she had

never heard of such a name and couldn't spell it

"What was his profession?" she asked

I told her her was a poet; she looked perplexed

"What's a poet?" she asked

I told her a poet was a person who wrote poems

She put that down, and that's what it says on the form:

Dylan Thomas—a poet (he wrote poems).