Tributes

Jhumpa Lahiri on Edward Hirsch

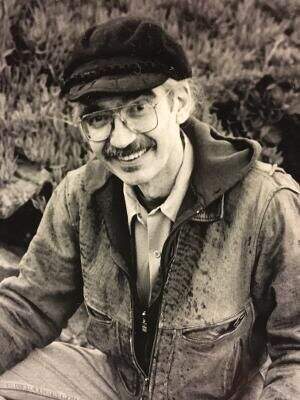

The first time I encountered the poems of Edward Hirsch, I was lucky enough to have them read to me by the poet himself. It was August of 1999 and I was in Vermont, a fellow at Breadloaf, surrounded by writers, hundreds of them, it seemed. There were those who were just starting out, eager to learn; those like me, who had a single book to their names; and those, like Edward Hirsch, who were in my eyes the real writers, with many books and much experience behind them. For two weeks we all lived and dined together in the mountains, either taking or teaching or, in my case, helping to teach, writing classes. But in my memory the central event of Breadloaf was the series of readings held each day of the conference, from morning until late at night. It was impossible to attend everybody's reading, and thus it would have been easy to miss Edward Hirsch. Fortunately, I did not. I no longer recall exactly what he read only that, in the process of listening, I fell quickly in love with his words. I was too shy to approach him to say so, but he was kind enough, at one point, to speak to me, saying nice things about my writing. By the end of the two weeks, I had listened to countless fiction writers and poets. Edward Hirsch's reading was the one I'd savored most, the one I treasured, like the single stone one is compelled to pick up from the sand after a visit to the seashore.

Back in New York, I told Alberto, the man who was eventually to be my husband, about my time at Breadloaf. I talked about the mountains I could see from my desk as I wrote, and the pond I'd swum in that was full of frogs, and the vast dark lawn I stumbled across every night, guided not so much by the faint beam of my flashlight as by the stars. And oh, I added, and there was a terrific poet there, someone by the name of Edward Hirsch. Not only had Alberto heard of him, but he had a story to tell. Long ago, years and years before Alberto and I met, Edward Hirsch had visited a poetry workshop Alberto was taking at the University of Pennsylvania, taught by Daniel Hoffman. Edward Hirsch had been at the table the day one of Alberto's poems was discussed and praised, and as a result, Alberto forever associated Edward Hirsch with a wonderful moment in his life. Alberto remembered that Edward Hirsch had been a young poet back then, the author of a single volume. Then, from the bookshelves we were by then sharing, the contents of which I thought I knew, he pulled out a signed copy of Edward Hirsch's first book, For The Sleepwalkers. It was printed on the thick, textured paper that is rare these days. The spine was flaking, the back cover missing a small piece, the price just five dollars and ninety-five cents. Today the book is in two pieces, split between pages thirty-four and thirty five, held together, when it is not being read, by a rubber band.

For the past few weeks I have had the extraordinary pleasure of reading nothing but the poems of Edward Hirsch. I cannot recommend this activity more highly. In my reading life, I regard poems as beloved but parenthetical things, what I turn to when I crave a change of pace from prose. But there is nothing parenthetical about Edward Hirsch's poetry. It is, rather, a capacious celebration of subjects dear to my own heart: painting, music, people, one's family, the seasons, other writers, classical antiquity. He evokes the profound pleasure I have felt, walking through the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, or wandering, last November, through the neighborhoods of Rome. He voices my desolation when waking up, without wanting to, at four o'clock in the morning. It is as if he has accompanied me to those places and in those moments, recording and expressing what I cannot. And yet these are the words of a separate imagination, someone I barely know, a moving chronicle of another person's joy and uncertainty and sorrow and loss. The most important thing Edward Hirsch has taught me is that in the best of writing, there is no hierarchy of subject matter—that there is nothing more or less worthy of the writer's consideration, reverence, compassion. In these past weeks my mind has been saturated with his images: of blueberries poured into an iron sink, of a frail, ailing father shuffling down a hallway, of walking home on an autumn day, of two suitcases filled with drawings by children of the Holocaust.

With equal devotion Edward Hirsch visits the ordinary and the extraordinary, the incidental and the grave. The trademarks of his poems are things I strive to bring to my own writing: to be intimate but restrained, to be tender without being sentimental, to witness life without flinching, and above all, to isolate and preserve those details of our existence so often overlooked, so easily forgotten, so essential to our souls. It would be hard to choose a favorite, but at the top of my list of Edward Hirsh's poems is one called "My Grandmother's Bed." It is a fairly brief poem about a boy going to sleep in his grandmother's Murphy Bed, and it shows me why poems are necessary, why they can accomplish things that novels and short stories cannot. The poem contains much of what fiction does--characters, setting, action, tension—and while it tells a story, it transcends fiction's earthbound constraints, occupying a distinct linguistic ether. To me it is a perfect example of why poems are more for being less. Like his grandmother's bed, miraculously pulled out of the wall at night, Edward Hirsch's poems are discreet yet magical things, always inviting, beautifully constructed out of ordinary words we all know and use. "How she pulled it out of the wall / To my amazement," the poem begins.

This is exactly how I feel when I open one of Edward Hirsch's books. A universe appears where there had not been one before; I am transported to a provocative, most welcome place, as rich and restorative as the best of dream-filled sleep, as consoling and as necessary.

Among Edward Hirsch's works of non-fiction is a fine book called How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry. When it comes to Edward Hirsch, this process is in my opinion inevitable. Tonight we are particularly lucky, for we do not even have to do the work of reading, but have only to fall in love, perhaps for the first time, or perhaps, in my case, yet again. Please join me in welcoming him.

(On September 21st, 2004, Jhumpa Lahiri introduced Edward Hirsch at The National Arts Club.)