Tributes

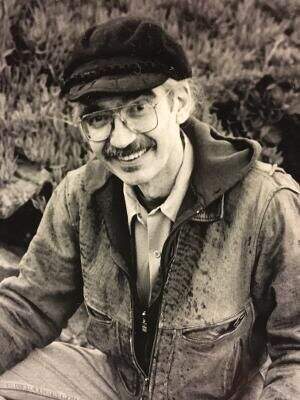

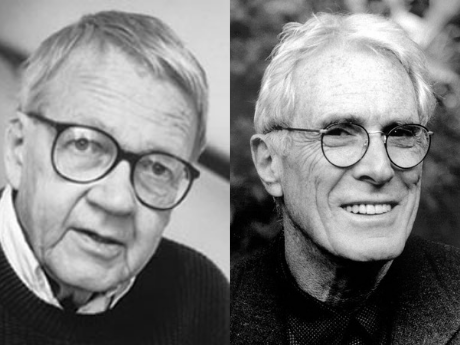

Mark Strand on Donald Justice

I am not sure that Don Justice would want much said about him. He was a fastidiously private person where it mattered, that is, in public. He did not like to call attention to himself, at least not overtly, and cultivated an amiable distance between himself and others, which, over time, would close and finally cease to exist. He was the "thin man" of his poem "The Thin Man."

I indulge myself

In rich refusals.

Nothing suffices.

I hone myself to

this edge. Asleep, I

Am a horizon.

Don was repelled by affectation, but was oddly attracted to the theatrical. He could be cutting about the claims others made for themselves, but was forgiving if the claims were presented with style. His own style was shaped by the thin man's "rich refusals." He chose his words for the weight they carried, not for the space they filled. A thin man indeed, but one who's presence was unignorable.

My friendship with Don began in the early sixties at the University of Iowa where he was teaching in the Writers' Workshop and where I was a student for one year and thenceforth, for several years, a teacher. Don and I tended to agree on matters relating to poetry, we even collaborated on poems and gave each other writing assignments, the most notable of which, and perhaps the only remaining, is Don's "Incident in a Rose Garden," a brilliant retelling of the Sufi fable that prefaces John O'Hara's "Appointment in Samarra." But we spent more time playing ping pong, pinball, poker, cribbage, and various board games. We even invented a boardgame we called "Art Market," which, alas, was pre-empted by an inferior one, naturally, that Parker Brothers marketed called "Masterpiece." Don took games seriously, was very competitive, so much so, that for me, and I suspect for others as well, losing to him came as something of a relief. In the classroom it was different. No competition existed there. Don was clearly much more accomplished than the rest of us. A great teacher, he was unfailingly sensitive to the needs of a particular poem and was able to extract its buried meaning while politely acknowledging its apparent meaning. Then, once the excavation was accomplished, he would speculate on ways the poem might be resuscitated. There was a dignity, never forced, about the way he treated our poems, even those of little promise. It is remarkable that Don's students, many of whom are among the best known poets in America, write nothing like him. I know from my own experience that he urged me to cultivate what was idiosyncratic in my work.

The reserve that Don exhibited so palpably in his relations with others is, for me at least, one of the endearing and enduring features of his poetry. Yet one could never say that his poems are impersonal. His intensely rational and skeptical nature, though almost always present, would sometimes undergo a beautiful and heartbreaking Symbolist revision when childhood or the past was invoked. His apostrophes, so full of feeling—full of anguish really—in their attempt to call back into being that which has been lost, are delivered with a tone of dignified surrender—surrender to feeling of course, but dignified by being first and foremost fictive elements within the matrix of the poem: little lost Bohemias of the suburbs; seasons of half forgetfulness; lost and wordless; indecipherable blurred harmonies; ineluctable blues of the middle class.

Don's poems are always recognizably his. A kind of metrical languor regulates their movement as they unfold unhurriedly, sometimes circuitously, even reluctantly, towards their end. He could linger on a detail as if its retrieval were imperishable in the imperishable twilight of the poem. He was an elegist whose tireless evocation of loss became a form of replenishment, a radiant fullness. And it was not just his own past he returned to in his poems. Often he cast his lines back to other poets' poems, reimagining them in the context of his own life. Thus, for example, the humorously grandiose first line of Wallace Stevens' poem "Anecdote of a Jar," "I placed a jar in Tennessee," becomes the equally humorous and grandiose "There is no music now in all of Arkansas," the first line of a poem written for his friend the pianist Thomas Higgins.

Don's precision in esthetic matters and his courtesy in personal ones masked, I believe, a vivid inwardness—an inwardness of the sort we sense in the paintings of Edward Hopper or even further back, say, in the paintings of Piero della Francesca. It may have been a sympathy with such projections of hiddeness that moved Don late in life to try his hand at painting. I can recall many instances of his phoning me up and asking me—because I had once been an art student—questions relating to technique. He wanted his paintings to look like they were done by a painter and not a poet. He had no desire to appear amateurish, nor to have it seem as though the making of his paintings entailed a struggle. In his artistic pursuits, which, it should be mentioned, also included musical composition, he was very much a purist, but quirkily and beguilingly so. Still, the work for which he will be remembered is of course his poems whose principle beauty lies in the wistful articulation and sad acknowledgement that little or nothing survives the great drama and effort that is life. Sorry news, but conveyed always with a certain dark, inimitable charm, beautifully, unforgettably.