Tributes

Susan Wheeler on Ben Belitt

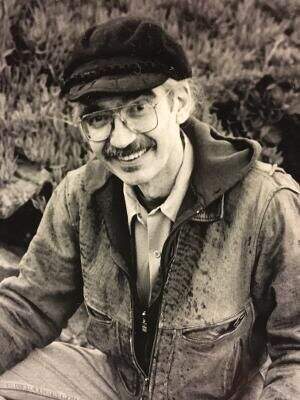

The last time I saw Ben Belitt, in the summer of 2001, he took me out onto his back porch overlooking Paran Creek and pointed to the flowers filling his trough planters. "Consider the life-force!" he said, triumphantly. I do.

His was extraordinary. What vigor he had in that tidy form of his! Visiting twenty years earlier, I had gone with him to Powers Market across the street from his firehouse home in North Bennington, Vermont. Powers was part of his daily routine. Addressing the butcher with a flurry of ornate phrases fit, perhaps, for a 17th-century address to a king, he had embarrassed me as though I were twelve and he, my mom. But now, in 2001, his strangely self-effacing gift for gab—always focused on ideas or on me, never initiating remarks about himself—reassured me that although his teeth were out and the sink was filled with dirty dishes, he was as keen and as full of the life-force as ever.

He was assigned to me as my first-year advisor at Bennington College in the fall of 1973. Daunted by fellow students' sophistication, working as a gas jockey and sometime- mechanic throughout the following four years, I studied with him off and on until I graduated. He helped me choose a poem that would win a McDonald's employee prize (in a short stint before gas station work took over); he patiently heard out my lament over a friend who had returned home to tell his partner about our one-night stand, responding, "These boys who have to go home with their tails between their legs and confess all!" His immense, generous readings of our poems, in the one workshop I took with him, filled the air like cumuli each week, making our aspirations rise too.

For my own deluded reasons, I did not read any of his work until well into my third or fourth year. That was fortunate because something mandarin in his poetic manner might have persuaded me that our first year's undertaking— to flatten out the language of a poem about my great-uncle's death, week after week, line by line—was a matter of the blind and the blind, but by then I was too oblivious and too enamored of him to spook. Although my language kinked up like hair again, the control he taught me in that long, first endeavor together was a gift—and one key to the astonishing performances of his poems and translations.

* * *

His students could never figure out why he wasn't better anthologized, more recognized. Proffered was always that he was disparaged for his translations, those of Neruda and Lorca, Machado and others. The translations took liberties, much as Lowell's did, in his deliberate enterprise to re-imagine the poems in English, to create parallel, vital new works. Lowell weathered his own storm over like choices, but Ben did not, even though Rafael Alberti cited Ben as the best of his many translators; dismissed for these, Ben's work was dismissed in full.

This explanation may be more than apocryphal, but the vagaries of recognition are that: vagaries. It could well have been that a minimalist, first-person era had little truck with a poetry that fashioned even its most intimate revelations in language like a fire-storm:

Night. Night as I would have it,

night that I sought in its festival guises as sun-stone,

planetary rose, salt with its faceted enigmas, fern,

fires of the sexual whale saying: I am. I made it! in

catastrophic sperm, love's underside, love's failings, tears--

yes, love's ignominious reversals that my heart's starvation

would have reversed, if it could: night with its names for powers,

dominations, fears: houses, Homeric fictions: Dante astray

in the tiger-taken wood: Hell with its vertical vengeances:

and night, night without respite or guile, the light of common day.

("The Gorge: Cuernavaca")

His mind seized on tropes, on iconography: mummies, doppelgangers, quarks. Nature was fierce, fecund, indifferent; coming to terms with this involved a wrestling. His was a gorgeous, guttural English, with both Chaucer's choices and court English:

Night-sweat clotted their palms. They tasted

their gall. The sumac flickered a swatch

of its leaves in the lichens and venoms,

a dazzle was seen in the fog

as a vegetal world gave way to a uterine,

pitch pulled at their heels and blackened

their knuckles, the bog-laurel's fan

opened its uttermost decimal and showed them the Bog.

Paradisal, beyond purpose or menace, dewed

like the flesh of an apple with the damp

of creation, the disk of the pond glowed . . .

("On Quaking Bog")

The disk of the pond! What overtakes the reader is that within the piling-on—the baroque accrual of utterances (it's hard not to catch his word-fever while typing "him")—is a stellar economy of image. What embarrassed me with the butcher at Power's Market was nothing less than Ben's recognition that language and life alike needed to be breathed into, imbued, awakened with the life-force whether vegetal or animal. There was something, well, incongruous to me then: how, within the run-down finitude of North Bennington, could he hope to help anything to dazzle?

Originally published in Crossroads, Spring 2004.