Visiting Poet

Visiting Poet: A.E. Stallings on Dimitra Kotoula

Three poems

Landscapes I

It’s an icy day.

A lifeless wing of morning light

hangs there, mundane

stubborn.

The smell of frost and the red leaves of the plane tree steaming.

Fresh furrows of soggy raw material

my hands

held straight out before me

devout and servile

worn by desire

sullied by the mud of self-indulgent nostalgia

gather their bearings.

Staying faithful to this light

I learn myself more clearly

I remember myself more clearly

beyond prediction or truth.

The autumn smoke rises serenely.

The forest of my troubled thought

rustles above me.

A sound fades red in my mouth.

Close your eyes

Close your eyes well to—

I you and this.

A handful of grief is scattered across the sea.

The sea is glorious.

We have no glory.

Only our hands a couple now

white hands amid green

worn down by desire

sullied by the mud of self-indulgent nostalgia

borrowed hands

live

for a moment, almost bright

then eclipsed

a small violent army of regal frivolity

only our hands a couple now

—but without wings—

wrapping and unwrapping promises

forcing back the decay

while we lie silently

in the dark

looking at each other

while we hold each other

silently

in the dark

and the heart asks for nothing

—for we are poor—

just breathes the rhythmical breath

of its own relentless pounding.

Case Study VI

(On Poetry)

The sun spreads an intelligent shadow over the reliefs.

Sweaty summer sky descends.

History persists—

(just think: a piece of your life

has now finally come full circle)

like a bothersome gadfly.

The mystical one shines with his God

and the soul of things

—O, blessed gadfly—

knows the poem

and like a thin breeze

settles below its dome.

Landscapes VIII

But—

what could have any meaning now.

The lowering sun grazes the edges of sky.

The sea is now ready.

The moment

polished

radiant

poised with fecund promise

at the edge of the green fresh leaf a soaring dart.

I would blossom into the poem.

No sound.

Not a noise was found to redeem it.

Translated from the Greek by Maria Nazos.

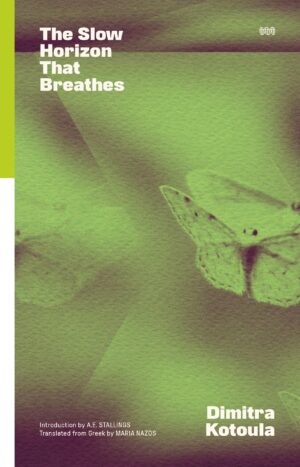

Poems by Dimitra Kotoula, translated by Maria Nazos are reprinted from The Slow Horizon That Breathes (World Poetry, 2023). Copyright © 2023 by Dimitra Kotoula, translation copyright © 2023 by Maria Nazos. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Tender Lavish Power: The Poetry of Dimitra Kotoula

Dimitra Kotoula, born in Komotini in 1974, a few months after the Greek military junta fell, published her debut poetry collection, Three Notes for a Melody, in 2004, the year that Athens hosted the summer Olympics. That year proved to be a turning point for Greece. It was a time of naïve optimism in the future, fueled by euphoria at having joined the Eurozone in 2001 and the success of the Games; instead, near economic collapse loomed only a few years later. Kotoula—with an unusual reticence for a young Greek poet—did not publish her next collection, The Constant Narrative, until 2017, by which time an economic crisis-cum-depression had held Greece in its death grip for close to a decade. These two collections, however, were already sufficient to ensure Kotoula’s place as one of the poets to reckon with in her generation, a poet of high modern seriousness and lyric grace, who yokes intellectual and philosophical concerns to physical sensuality. Feminist is also a word that pops up in descriptions of Kotoula’s work, by which perhaps we mean an unapologetic female gaze and point of view infusing her work. The three American poets she has translated into Greek—Jorie Graham, Louise Glück, and Sharon Olds—could serve as keys to her own gifts, three mystic godmothers associated respectively with Kotoula’s distinctive qualities: lacunose cerebral abstraction, direct lyric authority, and engagement with the body and its desires.

Kotoula’s generation of Greek poets, whose birth or early childhoods coincided with the rebirth of Greece’s own fragile democracy, and whose artistic maturity coincided with the years of “crisis,” might well be called the Crisis or Austerity Generation. This is a generation that never, as adults, experienced the (sometimes kitschy and touristy) Greek prosperity of the ’80s and ’90s, and who, if they remained in Greece—many chose to leave during the years of dismal unemployment and Greece’s “brain drain”—had few opportunities to pursue the professions for which their high level of education had equipped them. (Kotoula, I note, studied Archaeology and the History of Art.) They also faced, within Greece (I say this as an outsider), something of an entrenched gerontocracy among literary institutions and prize-giving bodies. What this generation tends to share, therefore is an almost cynical skepticism of careerism, a passionate belief (or absurdist faith) in the work for its own sake, and an acute and sometimes ironic historical sense, being the children and grandchildren of people who had experienced military dictatorship, civil war, famine, and German occupation. These are also poets who often have excellent English—the lingua franca, as it were, of the larger poetic world—and for whom writing in Greek and for a Greek audience can be considered a conscious choice.

One of the things that impresses me about Kotoula’s work is its confident sense of its place in Greek arts and letters, being in dialogue with, for instance, George Seferis and C. P. Cavafy, with whom Kotoula shares a tragic historical sensibility. “Summon Mr. Seferis to speak with diplomatic calm of our European Hellenism,” Kotoula asserts in one poem. More indirectly, Seferis’s poetry also haunts Kotoula’s Greek landscape, with the sea and

the cicada, the sun on marble “spreading an intelligent shadow over the reliefs.”

Kotoula engages with Cavafy even more intimately, entering the poet’s mind in an ekphrastic poem at two removes, responding to Cavafy’s poem “On Board Ship,” in which the poet, looking at “this little pencil portrait. / Hurriedly sketched, on the ship’s deck” remembers a beautiful young man “sensitive almost to the point of illness,” from an afternoon long faded into the past. Kotoula, though, rather than having Cavafy remember these things from long ago, has him try to forget. Paradoxically, the poet (Cavafy-cum-Kotoula) fetches up instead an even more visceral and specific recollection that becomes reenactment, reincarnation:

(the youth unclasps his hair

banishes memory

face dampened by laughter

with bite marks yet from the light

beneath the flesh)

The ekphrastic is one of Kotoula’s primary modes, and where she departs most perhaps from her major Greek models. Landscapes are arguably one kind of ekphrasis, and there is a more traditional kind in “The Body of Dead Christ in the Tomb,” after the Hans Holbein the Younger painting; perhaps most interestingly, as a kind of genre crossover, we have the “Head of a Satyr,” an anti-ekphrastic persona poem in the voice of the important, and deeply troubled, modern Greek sculptor Yannoulis Chalepas (1851–1938). From the marble-carving island of Tinos, Chalepas had a promising beginning to his career, studying in Athens and then the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, before he lost his scholarship and, in 1876, had to return to Athens. Two years later, he suffered a mental breakdown, and began destroying his own works:

It is 1878.

The Acropolis exists.

This country exists (does it?)

under watch—so be it!—

and in crumbling condition.

It was impossible to read or hear these lines in the midst of the Greek crisis—as I did at a reading in 2013—and not feel that they gestured to the punitive and soul-crushing austerity measures of that era. When Chalepas did regain his wits and his creativity, in his “post-sanity” period, one of his first acts was to return again to Athens and prostrate

himself before the Acropolis, a symbol, for him, of health and reason.

Kotoula reminds us of the “relentless weavings of time / in and out of History.” “History persists,” she writes in one poem, and in another she refers to the “wail of History.” Even so, it is surprising to find, as we do here, a poem that engages from a nonpartisan perspective with the Greek Civil War—a somewhat taboo subject in itself. For Kotoula, it is the innocent bystanders of history, the civilians caught up in its crushing gears and cogs, that elicit empathy and engagement. This position of being caught between sides also manifests itself in “The Poems of Yes and No,” a poem that addresses the absurdity of the 2015 Greek referendum, where everyone seemed to be passionately voting “yes” or “no,” but each to a separate, private question. Pulled, perhaps, between the “Right” and the “Left,” Kotoula finds the spot-on deep literary metaphor, “boustrophedon,” deep in the Greek language and alphabet itself:

Now I write as the ox plows:

left to right in one line, right to left in the other—

Few poets are so good at writing about contemporary events while holding them at arm’s length, squinting at them through the ironic monocle of the Muse of History.

Maria Nazos, herself a talented and accomplished poet, proves an ideal translator to bring these difficult, delicate, durable poems into English. Nazos’s own well-tuned poetic ear in English, her humility in her collaborative approach with the poet, and her deep experience with Greek—arguably her mother tongue, even if long submerged—mean that English readers have much to be grateful for here. Even readers with Greek, who will be able to compare and contrast, making their own triangulations, will find their understanding enhanced by Nazos’s interpretations. Above all, readers of this volume will be able to bask in these poems’ “tender lavish power.”

A.E. Stallings is the author of four poetry collections, a frequent contributor to Poetry and the Times Literary Supplement, and the translator of The Nature of Things by Lucretius (Penguin Classics). She directs the Poetry Center in Athens, Greece.

Dimitra Kotoula is the author of three poetry collections and the recipient of the prestigious Chartis prize. Her poems have been translated into thirteen languages. She was the first to translate Louise Glück’s poems into Greek, and has also translated the work of Jorie Graham and Sharon Olds.

Maria Nazos’ poetry, translations, and essays are published in The New Yorker, Copper Nickel, North American Review, Denver Quarterly, and Mid-American Review. She is the author of A Hymn That Meanders (Wising Up Press) and the chapbook Still Life (Dancing Girl Press). She has received scholarships and fellowships from the University of Nebraska, Vermont Studio Center, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. Her first book of translation is Dimitra Kotoula’s The Slow Horizon That Breathes (World Poetry, 2023).

A.E. Stallings' introduction, "Tender Lavish Power: The Poetry of Dimitra Kotoula," is reprinted from The Slow Horizon That Breathes (World Poetry, 2023).