Visiting Poet

Visiting Poet: Ilya Kaminsky on Serhiy Zhadan

Three poems by Serhiy Zhadan

"Of all literature"

Of all literature

and all language

Iʼm most interested in words

used to address

the dead.

What if someone spoke a sentence

that could stir the sonic field of death?

Listen to me,

you—deprived of the sweet receptors of song.

Listen to me now,

hear my whisper,

distorted by the acoustics of nonexistence.

Listen to me,

you—marked by dialects, like scars throughout your lives,

you—whose throats were scratched since childhood by the burning needles of the alphabet,

you—singers who could imitate bird calls.

I know—it is unfair

you cannot answer

the voices calling out to you from the mist today,

you cannot say anything to defend yourself,

you cannot protect the vacant land of night

between memory and expectation.

But language is important even after death,

like the deepening of a riverbed,

like the rise of heat for the first time in autumn

in a great home.

The only rule—grow roots,

break through.

The only chance—reach out for a branch, grab hold of a voice.

There is nothing else.

No one will remember you for your silence.

No one but you can name the rivers nearby.

You who are only echoes,

you who are filled with silence,

speak, speak now,

speak as grass,

speak as frost,

speak as conductors of music.

"In the summertime"

In the summertime everyone wants to feel the cool touch of the river.

The birds in summer gardens are crazy and unrestrained.

Two trees stand on the hill, facing each other

like two people who once shared the same hospital room and now meet again.

The summer is so endless that everything stands still.

The moon rises in the evening over the roadside thorns.

The days are so long that when dusk finally arrives

everyone revels in the dark and doesnʼt sleep.

The sky is like a teenager with textbooks, sorting out the stars,

arguing with the birds, as if they were trespassing.

The leaves are motionless, the branches silent

as one tree listens to the other.

"This is a good opportunity to be thankful"

This is a good opportunity to be thankful

for being born in the twentieth century,

for having the chance to see

the borderline of history,

for the chance to walk through crowded train stations

that slowly empty and then fall silent.

You can be thankful for the opportunity

to write letters by hand,

then hopelessly depend on the postmanʼs leisurely delivery,

only to experience the slow motion of the calendar,

its female sensibility.

Give thanks for that particular feeling of time

measured by how many pages youʼve read

each night.

Be thankful for space,

firmly outlined in pencil, like a button

held tight in a childʼs hand.

Those who lived through wars and great upheavals,

stand by windows, parting with

their troubles, as if parting with a dying neighbor.

They notice who lived longer,

who won the doubtful honor

of watching their enemyʼs funeral.

The bright children of the twentieth century

dissolve in the dark, like railroad workers

on a night shift.

In the morning the train arrives at the station.

Dawn greets all those who got off along the way,

tempted by a lamplight behind the trees.

Dawn greets those who exit at the last stop.

Only joy is left behind,

and despair.

The damp mist entwines with

the careless word.

Stay with me, music of the street.

Stay with me, this feeling of victory.

This feeling of justice.

This rhythm.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Virlana Tkacz and Wanda Phipps

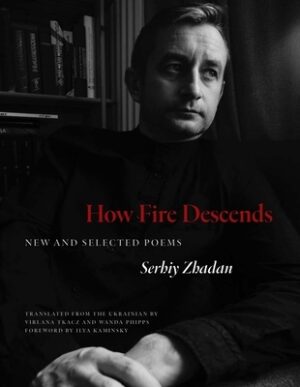

Reprinted from How Fire Descends: New and Selected Poems by Serhiy Zhadan; translated by Virlana Tkacz and Wanda Phipps; foreword by Ilya Kaminsky. Published by Yale University Press in the Margellos World Republic of Letters series in October 2023. Reproduced by permission.

Ilya Kaminsky on Serhiy Zhadan

Anyone who has seen Serhiy Zhadan perform with his band, Zhadan i Sobaky (Zhadan and the Dogs), will tell you that it is something to behold. No poet since Allen Ginsberg has commanded such a magnetic presence onstage. The audience goes wild, hundreds of people jumping up and down for hours.

More than simply a rock star, however, Zhadan is arguably the most beloved Ukrainian poet of his generation. Western readers encountering him for the first time might ask, How can such a thing be, in our day and age? How can a poet command such a space, and such a presence, in public life? How can a literary artist also be a rock star, and also be a symbol—a civil interlocutor, a public voice of moral authority, a prominent defender of his city in time of invasion, a man who appears on TV discussing poetry even as he daily goes out into the streets under heavy bombardment to deliver food, clothes, and medicine to those in need?

* * *

To answer that question, let me provide some context: In the 1990s, in newly independent Ukraine, the people looked to poets for guidance on how to rebuild a vibrant cultural life. It was poets, not fiction writers or painters or musicians, who led public discourse in the arts.

I think, for instance, of Bu-Ba-Bu, a legendary trio of poets who electrified audiences with their public performances. Bu-Ba-Bu, short for burlesk-balahan-bufonada (burlesque-bluster-buffoonery), relished the carnivalesque and celebrated the newfound creative freedom in the aftermath of the demise of the Soviet Union. These poets (Viktor Neborak, Oleksandr Irvanets, and Yuri Andrukhovych) often performed to rock music and made appearances at various festivals to wide acclaim. But the excitement their public performance of poems set to music generated is perhaps the only similarity between Zhadan and the Bu-Ba-Bu generation. Whereas the poets of Bu-Ba-Bu hailed from West Ukraine and were rooted in the Ukrainian-language literary traditions, culture, and folklore of that part of the country, Zhadan is the poet of the post-Soviet landscape, the largely Russophone eastern Ukrainian borderland, notorious for its stagnation and crumbling social order. Writing across literary genres and modalities, he aims throughout his work to give a voice to the forgotten people of the borderland region.

In this region that he calls home, Zhadan searches for language that connects with and makes legible eastern Ukrainiansʼ experiences. The bold, direct negation here becomes an instrument of that connection, a forceful reaching out:

Just donʼt call it a language.

Donʼt call these vines that grow and invade

the surrounding silence a language.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

These are anything but languages.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

These could be the songs of buildings

from which entire families were evicted.

These could be fonts

for announcements in newspapers

burned to heat the barracks.

To speak such a language

is to converse with iron

or argue with linden trees.

* * *

Born in 1974 near Starobilsk, a town in eastern Ukraine, Serhiy Zhadan has spent most of his life in the city of Kharkiv. There he published his books, raised a family, and participated as a prominent activist in rallies supporting the Orange Revolution in 2004 and the Maidan Revolution of Dignity of 2013–2014. In one memorable incident, he and his compatriots were stormed by the pro-Russian crowd and ordered to kiss the Russian flag. When he refused, Zhadan was beaten and suffered a concussion. These dramatic historical events have impacted the poetʼs style: after Maidan, the poetʼs work took a marked documentary turn. Today, as the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia continues, Zhadan resides in his hometown, supporting his fellow Kharkivites as a volunteer defender of a city under active bombardment.

The spiritual and human landscapes of Ukraineʼs eastern region, of the post-industrial world where solitary voices search for one another, are present throughout Zhadanʼs novels, essays, theater pieces, and poetry. He is relentless in his search for speech patterns and registers that can genuinely reach another human:

Itʼs not voices that make up time

but punctuation,

which creates an outline, gives us

moments to inhale and exhale,

mapping out

our connections,

our diff erences,

our similarities.

Like his poetry, Zhadanʼs fiction is filled with the paradoxes of a post-Soviet existence, in which people ache for one another and for warmth in the most unlikely situations. It is a landscape where, as his poem “In the summertime” describes it, “two trees stand on the hill, facing each other / like two people who once shared the same hospital room and now meet again.” A landscape both raw and somehow impossibly near, where “the sky is like a teenager with textbooks, sorting out the stars, / arguing with the birds, as if they were trespassing.” Which is to say, it is a place where lyric strangeness can be found even in the most ordinary instance. This work resonates especially with the generation that came of age in Ukraine during the 1990s and 2000s: these readers see themselves in Zhadanʼs rendering of the post-Soviet world, in which “winter appears like a book of poems / no one will ever publish,” where “waiting for snow” is “like waiting for the war to end.”

But Zhadanʼs writing also manages to transcend his own landscape through his exploration of the dualities and connections between seemingly unlike things. For years he has sought to define the mysterious relationship between war and language. He is a public person who seeks to render visible the most intimate experiences of lovers, knowing all too well that “a language disappears when no one speaks of love.” He is a symbol of his country's hope and resistance who has for a long time employed the dual forms of prose and poetry to give a voice to disillusionment, a poet who finds warmth in raw and gritty conditions.

What is a man to do in the middle of crisis?

**

So what does this man do?

He writes poems.

Spreads them out on the table,

polishes them.

As if getting shoes ready for a child.

**

The duality of our existence is that even in the midst of crisis there is gentleness, showing itself to us through images of the streets:

How children embrace the shade like a mother.

How dogs fall silent, seeing the sun . . .

The tensions between opposites produce sparks; even in the most mundane moment we can find memorable turns of phrase, unexpected tonalities and music. And if it is hope we are looking for, we will find that, too, in this world at crisis, for that too is a duality Zhadanʼs work encounters

And summer will come

with trains that return to the city

like fishermen.

All of this, of course, poses many challenges to Zhadanʼs translators, for they must translate not simply the words, images, and music but also what these images and music mean in a very different culture and a very particular historical moment. They also need to find a way to convey the function of poetry in that culture—its impact.

So when I say Zhadanʼs work has taken a more documentary turn, a reader might perhaps think of Charles Reznikoff's important work making poetry from court testimonies after the Holocaust or C. D. Wrightʼs moving poems dealing with the U.S. prison system or civil rights movement. Or from another perspective, one might think of Tracy K. Smithʼs erasure of the U.S. foundational historical document to make it into a lyric statement of resistance. These, among many others, might offer surprising and apt parallels, but Zhadanʼs poetry aims to do something else, in its very particular landscape and moment in time. His aim is to match the tone of his epoch.

Which is to say, Zhadanʼs documentary chronicles in verse find poetry in unlikely spaces: Soviet-style apartment blocks, concrete streets that look exactly like hundreds of other concrete streets. He writes poetry with a kind of journalistic perspective on locales and people who have been missing from literature, but his documentary mode blends lyricism and irony, even sarcasm, to showcase the tonality of the post-Soviet epoch.

Zhadan consciously tries to bring these prosaic, testimonial elements into lyric, investigating the lives of people on the margins of the state and he attempts to do this not just in the content of the work, but in the timbre and pitch of the voice that says the words. At the end of the day though, the poet of the people must realize that he is not simply shouting at the crowd of people from his podium, he is also one of the voices in the crowd. Zhadan understands this:

I've seen how birds fall in the snow like schoolchildren,

when they feel too lonely above.

This happens every time winter arrives.

This actually happens to all of us.

It will happen to me too in the end.

I will come to the lake holding a lantern.

Perhaps this realization is what shows us that a rock star is first of all a lyric poet, one who knows that “music . . . circulates in the lungs of men,” yes, but also one who suspects that “the limits of loyalty are still marked by / night music.” This knowledge is as heartfelt as it is ironic:

Poets buried near shopping malls

make good tourist attractions.

A poet should be useful even after death.

Not too convenient alive,

unpredictable in the theater,

like a stone in a child's hand,

shocking like a bird flying into a kitchen window

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Cities bury their poets,

like jewelry hidden under clothes.

This perspective is not for the faint-hearted. But I doubt anyone opening a book of poetry by a contemporary Ukrainian poet is looking for platitudes. What you find here is a voice whose language is marked by violence and war:

Listen to me,

you—deprived of the sweet receptors of song.

Listen to me now,

hear my whisper,

distorted by the acoustics of nonexistence.

Even while addressing us, Zhadan admits that it is quite another addressee he has in mind: “Iʼm most interested in words / used to address / the dead.” We have the opportunity—and the duty—to witness a poet in the midst of such a conversation. Perhaps that is why in wartime his public events gather hundreds of people who have lost loved ones and donʼt know what to do, donʼt know what language to speak to those who are no longer alive. Breaking bread with the dead is something poets have done for ages, W. H. Auden once told us, echoing Gilgamesh. Perhaps with that in mind, Zhadan presses the conversation farther, asking:

What if someone spoke a sentence

that could stir the sonic field of death?

What if someone spoke such a sentence, indeed? May you find many such sentences in this book, dear reader; I know I did.

Serhiy Zhadan is one of Ukraine’s most celebrated writers. He has received the Hannah Arendt Prize for Political Thought, the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade, and several international literature prizes. His books include Sky Above Kharkiv; Mesopotamia; The Orphanage; and What We Live For, What We Die For: Selected Poems. He lives in Kharkiv, Ukraine.

Ilya Kaminsky was born in Odesa, Ukraine in 1977, and arrived to the United States in 1993, when his family was granted asylum by the American government. He is the author of Deaf Republic and Dancing in Odessa and co-editor and co-translator of many other books, including Ecco Anthology of International Poetry, In the Hour of War: Poems from Ukraine, and Dark Elderberry Branch: Poems of Marina Tsveta

Foreword reprinted from How Fire Descends: New and Selected Poems by Serhiy Zhadan, translated from the Ukrainian by Virlana Tkacz and Wanda Phipps. Published by Yale University Press in the Margellos World Republic of Letters series in October 2023. Reproduced by permission.