Visiting Poet

Visiting Poet: Kristen Renee Miller on Marie-Andrée Gill

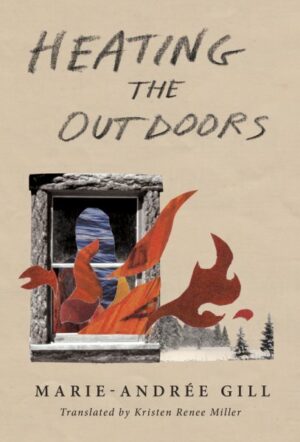

Excerpts from Heating the Outdoors

You’re the clump of blackened spruce

that lights my gasoline-soaked heart

It’s just impossible you won’t be back

to quench yourself in my crème-soda

ancestral spirit

*

Still, I wish we'd poached again, that you’d laced up my

fur in your fingerless gloves, that you’d wrung out my

heart like mounting a pelt to a frame. I’d have shown

you I can smile at myself as a carcass of the word

dread.

*

In the village we watch each other live; we turn to all

the cars that pass; we mark, with orange flags on the

edges of dirt roads, all the places we left our beliefs.

Translated by Kristen Renee Miller.

Kristen Renee Miller on Marie-Andrée Gill

Marie-Andrée Gill was born on April 26, 1986—or, as she likes to tell it, "the day Chernobyl went boom." An elder millennial like me, Gill spent her formative years steeped in ‘90s-kid culture—Super Mario, AIM chat rooms, Celine Dion, The Thorn Birds—from her home on the Mashteuiatsh reserve in the Saguenay region of Quebec where she grew up, a member of the Ilnu First Nation. Gill, who identifies herself as both Ilnu and Quebecoise, braids these influences in her work—pop culture references, Quebecois slang and profanities (sacres) evolved from the Catholic tradition, and the natural landscape of Nitassinan ("our land" in Nehlueun), the boreal territory and ancestral home of the Ilnu.

I first encountered Gill’s work when I picked up a copy of her book Frayer in a small, secondhand, Montreal bookshop. Gill, by that time, had already gained wide popularity among francophone readers for her distinct style and untitled micropoems. An award-winning poet and author of two books, she had been called "an icon in contemporary Quebec Indigenous poetry." But I didn’t yet know this when, opening to a page at random, I read the line: lécher la surface de l'eau avec la langue que je ne parle pas ("to lick the skin of the water with a tongue I don’t speak"). It’s a line about having an intimate connection through an unfamiliar medium—a line that seemed to perfectly encapsulate the act of translation, though now I also recognize in it the underlying sense of dislocation, of alienation within one’s "home" language.

What sets Gill apart from many other poets writing in French is her keen, personal awareness of it as a settler language. In Gill’s Pekuakamiulnuatsh community, the Nehlueun language has been largely replaced in daily life by the French now spoken by much of the community. A doctoral student in literature, Gill, who herself writes in French, focuses her creative work and academic research on the decolonial project of finding a "parole habitable" (a habitable language, a homelike speech). She hosts the award-winning Radio-Canada podcast "Laissez-nous raconter : L’histoire crochie" ("Telling Our Twisted Histories"), which explores "words whose meanings have been twisted by centuries of colonization." She crafts poems that echo the Ilnu oral tradition in their use of the colloquial, in their self-deprecatory humor. And she wields these poems to interrogate and reclaim the language, landscapes, and interpersonal intimacies distorted by imperialism, a project that threads through her newest book of poetry, Heating the Outdoors.

*

If you want to know where I am now,

that’s me, writing hey, what’s up

in zamboni meltwater.

*

On a bed of fir saplings, we touched that mute,

ephemeral beauty. We stumbled out, uncertain,

searching for the edible root of language, nursing our

dazzling wounds. Together we drove a street sweeper

over our ghosts.

In any case, we knew what to do with our bodies

between thunderstorms.

*

What remains:

crying laughing like everyone knows

the scent of laundry soap and two-stroke gasoline

and my clit like a ronde dancer

all alone when her turn comes

*

Heating the Outdoors is a breakup album of sorts—it follows the end of a turbulent love affair and chronicles everything from breakup sex to monitoring your phone for new messages to the healing power of listening to Celine Dion alone in your car. It describes, with Gill’s signature humor and humanity, the domestic monotony of post-breakup malaise: "I lay my remains on the stove, and my birds hide themselves away to die;" the awkwardness of chance encounters: "Fear, it’s running into each other at the minimart and not knowing what to do with our bodies;" and the speaker’s "clit like a ronde dancer / all alone when her turn comes."

The book contains much of what propelled Gill’s popularity in her first two works—her signature irreverence, her use of Quebecois sacres and slang, her self-deprecation and sense of humor. But upon its publication in the original French, Gill was met with criticism, sometimes couched as a benign surprise, that there was nothing "conspicuously native" about the new book. In one interview, Gill responded sharply to this perception: "There’s this weird attitude, this assumption about Indigenous literature—what do people expect? That we talk about eagles and wolves all the time? An Indigenous person can experience heartbreak without talking about their ancestors."

*

Landscapes all look like you when you light them up—

polluted woods and streams, uishkatshan

and hawks that appear when you wish for them,

maples along the coulees, shady folds

of the mountains, a sunset that pricks a line

of conifers and the tshiuetin that slaps the houses,

plates of good food and joyrides—

the seasons no longer hold any meaning

except in the arrangement of our bodies.

I’d like to say all that

and quit biting

the skin from my lips

*

I touch wood; I close my mouth, but I keep on repeating

to the encompassing silence:

if you are looking for me, I am home

or somewhere on Nitassinan;

all my doors and windows are open.

I’m heating the outdoors.

*

What Gill’s early reviewers may have missed, looking for the easy signposts of "conspicuously native" poetry, is the book’s important, deep-rootedness to place. Gill has always been a beautifully subversive writer of place. Her narratives are enfolded by their natural surroundings—and these frequently marred by the encroachment of imperialism, whether in the "polluted woods and streams," or "the music of our surviving animals," or "the clump of blackened spruce / that lights my gasoline-soaked heart." The speaker’s sense of dislocation as an ex-lover is matched and emphasized by her surroundings—Nitassinan, the ancestral home of the Ilnu, the physical reminder of the community's displacement by the Canadian government, the site of development and ecological decline, of abusive, compulsory residential schools operating as recently as 1991. Gill’s story of intimate, personal loss plays out upon this site of centuries of communal and cultural loss. And, as the lines between interior and exterior—between indoors and outdoors—begin to blur, her poems become a record of the daily rituals and inside jokes, the domestic settings and ancient landscapes that inform her identity, not only as a lover and an ex, but also as an Ilnu and Quebecoise woman.

*

It’s in the sacré of a sunrise

in the music of our surviving animals

in the sorrow of all that shines

in all the slowness

my shaky breath allows

I let time

tune its instrument

accordingly

Pekuakamishkueu poet Marie-Andrée Gill is the acclaimed author of three books of poetry, Beanté, Frayer, and Chauffer le dehors (La Peuplade). A doctoral student in literature, her research and creative work focus on the decolonial project of writing the intimate. Gill hosts the award-winning Radio-Canada podcast "Laissez-nous raconter: L’histoire crochie" ("Telling Our Twisted Histories"), which "reclaims Indigenous history by exploring words whose meanings have been twisted by centuries of colonization." She is the two-time recipient of both the Salon du Livre Prize in Poetry and the Indigenous Voices Award. In 2020, Gill was named Artist of the Year by the Quebec Council of Arts and Letters.

Kristen Renee Miller is the executive director and editor-in-chief at Sarabande Books. A poet and translator, she is a 2023 NEA Fellow in Literature and the translator of two books from the French by Pekuakamishkueu poet Marie-Andrée Gill. She is the recipient of fellowships and awards from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts, AIGA, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, the Gulf Coast Prize in Translation, and the American Literary Translators Association. Her work can be found widely, including in Poetry Magazine, The Kenyon Review, and Best New Poets. She lives in Louisville, Kentucky.