Visiting Poet

Visiting Poet: Mary Jo Bang and Yuki Tanaka on Shuzo Takiguchi

Three Poems by Shuzo Takigucki

Nocturne

From a glass where swallows live

a prisoner removes her gloves

A moonlight bath gives her the equipoise of one in mourning

Night clearly illuminates everything inside night

A fountain kept sewing the wrinkles of the empty bed

She is as slender as a keyhole

Soon, she felt freedom in her pelvic ring

Between today and tomorrow a white handkerchief

An endless holiday of red lips

The sediment of the sun is at the bottom of the glass

together with the sleepless birds

Man Ray

A dissected moon

The white teeth of light

meet the light’s ribs

Shadow-lovers live inside the body

Listen to whispers

on an infinite staircase inside an enormous eye

Lovely words

transform into birds of light

inside gigantic crystal oculi

Panthers all out of lovely light are standing on their hands

All the stars reside inside garments

Light’s naked body

Warm blood could run

faintly through a statue

The Conception of Wind

The wind with a graceful lamp

reduces the leaves of trees to ashes

Your salad days are shaken up

by the mammoth hinge of night

On an alabaster night

everlasting youth

closes and opens like wings

A dream thundered in

and twigs lost the stability of stars

Translated from the Japanese by Mary Jo Bang and Yuki Tanaka

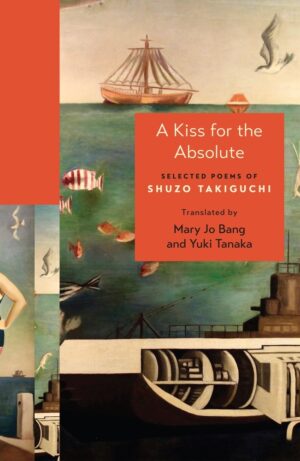

Reprinted from A Kiss for the Absolute: Selected Poems of Shuzo Takiguchi (Princeton Unversity Press, 2024) with the permission of the translators. All rights reserved.

From the Introduction to A Kiss for the Absolute: Selected Poems of Shuzo Takiguchi, Princeton University Press Lockert Poetry in Translation Series, translated by Mary Jo Bang and Yuki Tanaka

When The Poetic Experiments of Shuzo Takiguchi 1927–37 was published in Japan in 1967, tucked inside the book-jacket flap was a small, single-sheet, accordion-pleated appendix that began, “An other inside me made me choose this kind of title. The editor is of course myself.” That deferral to the ‘other inside me,’ recalls Arthur Rimbaud’s famous statement: “Je est un autre” (I is an other). This Rimbaldian echo is Takiguchi’s way of making it clear, with his “red-banded sardonyx wit,” that the I in these poems should not to be read as autobiographical, but as a constructed poetic entity—an impish shape-shifter who dashes quickly through a world overflowing with associative imagery and who hops from one literary, scientific, or philosophical allusion to another, speaks multiple languages, and has a penchant for comical puns. The resulting high-voltage poems appear to leap over Modernism and land with both feet firmly planted in a prescient postmodern sensibility. For all their slippery indeterminacy, the poems are also deeply political, rooted in ideas about artistic freedom, the freedom of the imagination, and especially the freedom to be one’s self in spite of a steady undercurrent of imminent peril.

Takiguchi was born in 1903 into an educated civic-minded family in Toyama Prefecture, on the Japan Sea coast. As the only son (with two older sisters), he was expected to follow in the footsteps of his father, and his grandfather, and become a physician. However, in April of 1923, when he first arrived in Tokyo and enrolled at Keio University, he chose Aesthetics as his area of study. There he became part of a coterie surrounding Junzaburo Nishiwaki, a poet and classicist who had studied English literature at Oxford University and had a deep interest in all things European and American, the more up-to-date the better. Under the influence of Nishiwaki, he was introduced to French Surrealism and began to write poems.

Once it was introduced, Surrealism quickly became the dominant avant-garde practice among young poets in Japan. The ideas behind it—privileging spontaneity and chance over the restrictive conventions of the past—had tremendous appeal. Takiguchi devoted himself to both documenting Surrealism and adapting it to his language and culture. In 1930, he published his translation of André Breton’s 1928 Le surréalisme et la peinture (Surrealism and Painting). He wrote to the Surrealists and they wrote back, initiating a correspondence that continued for years.

His poems are a mirror of his expansive personality, verbal facility, and vast erudition: Dadaist; Surrealist; multilingual (Japanese, French, English, as well as some Latin); indebted to a multinational literary and artistic past; and deeply committed to positioning poetry at the intersection of philosophy and modern psychology. The range of cultural references he includes in the poems is striking. He gives us, to list only a few: Plato, Hegel, Kant, Botticelli; raisin bread, quotes by Tristan Tzara and Gertrude Stein; Niagara Falls; Immaculate Mary; Cleopatra’s daughter; biblical King David (via a halibut who has David’s bearded profile); “a polar bear OUI”; the Surrealist writers Paul Éluard, André Breton, and Louis Aragon; and the artists Giorgio di Chirico, Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, Pablo Picasso, René Magritte, Joan Miró, Man Ray, and Salvador Dalí. He includes innumerable others, sometimes by name, sometimes by ingenious indirection.

Outside the narrow world of poetry and art, however, worrisome changes were taking place. In the 1930s, the military had gained more power in the Japanese government, moving the country toward an expansionist policy in Asia. In a timeline that Takiguchi later constructed about his life, he writes about an event that occurred in 1940, “The first exhibit of the Art Culture Association took place, but it was already a dark time, there was sense of foreboding on the faces of the painters. The pressure from the Special Higher Police and Intelligence Agency was closing in on the people around me. I felt both conflicted and isolated. I could feel the growing sense of a collapse of the surrealist vision and a sense of personal failure. In early winter, I coughed up blood from a stomach ulcer again. A certain friend came by and said I had completely missed the boat.”

On March 5, 1941, Takiguchi was arrested by the Tokko, the “thought police,” a branch of the Special Higher Police. Takiguchi was held for eight months for being a “thought criminal,” a category that included anyone influenced by the West. When released from the detention center on November 11, 1941, he was warned by the police that he had better “be more careful in the future.” The effect of the incarceration, and the ominous warning, appears to have been chilling. After his release from prison, Takiguchi wrote few poems that rise to the level of those in Poetic Experiments but he instead went on to become a visual artist, a major art critic, an exhibition curator, and a champion of avant-garde art. He helped revive the avant-garde scene in postwar Japan by spearheading an interdisciplinary art group called Jikken Kobo (“Experimental Workshop”) that was active from 1951 to 1957. His collected works in Japanese, published posthumously between 1991 and 1998, number fourteen volumes. They include his art criticism, his writings on photography and on Surrealism, his dream journals, his correspondence, and the contents of the book, The Poetic Experiments of Shuzo Takiguchi 1927–1937. The free-standing book, published in 1967, is no longer in print but continues to have a cult following in Japan. While some of the short poems have been translated into English, primarily in the early 1970’s by Hiroaki Sato, there has never been an English-language translation of many of the long prose poems, nor of the entire book. For A Kiss for the Absolute: Selected Poems, we chose those poems that best showcase Takiguchi’s formal range, as well as his intrepid use of language and ingenious rhetorical conceits.

Mary Jo Bang is the author of nine books of poems, including A Film in Which I Play Everyone and Elegy, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award. She has published translations of Dante's Inferno and Purgatorio. Her translation of Paradiso is forthcoming in 2025. She teaches at Washington University in St. Louis.

Yuki Tanaka was born and raised in Japan and teaches at Hosei University in Tokyo. His debut poetry collection, Chronicle of Drifting, is forthcoming from Copper Canyon Press in 2025. He received an MFA from the University of Texas at Austin and a PhD in English from Washington University in St. Louis.