Visiting Poet

Visiting Poet: Jack Jung on Kim Hyesoon

Three Poems

Bird's Poetry Book

This book is not really a book

It’s an I-do-bird sequence

a record of the sequence

When I take off my shoes, stand on the railing

and spread my arms with eyes closed

feathers poke out of my sleeves

Bird-cries-out-from-me-day record

I-do-bird-day record

as I caress bird’s cheeks

Air is saturated with wounds

Beneath the wounds matted over me

bird’s cheekbones are viciously pointed

yet its bones crack easily when gripped

The birth sequence of such a tiny bird

Poetry ignores

the I-do-bird-woman sequence

Woman-is-dying-but-bird-is-getting-bigger sequence

She says, The pain is killing me

When my hands are tied and my skirt rips like wings

I can finally fly

I was always able to fly like this

Suddenly she lifts her feet

Translation-of-a-certain-bird’s-chirping record

of I-do-bird-below-the-railing

sequence

Night’s carcass bloats

Waves of tormented spirits

One bird

All the nights of the world

Bird-carrying-the-night’s-nippleover-

the-pointed-as-an-awl-Mount-Everest sequence

Bird with dark eyes has shrunken

Bird has shrunken enough to be cupped in my hands

Bird mumbles something incomprehensible even when my lips touch its

beak

Bird’s tongue is as delicate as a bud

as thin as the tongue of a fetus

The tiny bird’s

kicks-off-the-blanket-kicks-my-bodykicks-

the-dirt-and-exits sequence

I end up doing I-do-bird even if I resist doing it

I end up saying this is not a book of poems but a bird

I’ll overcome this existence

Finally I’ll be free of it

Bird-flies-out-of-water-shaking-its-wings poetry book

Now scribbles of Time’s footsteps appear in the book

Scribbles left by skinny bird legs

made with the world’s heaviest pencil

Perhaps there’s a will left in the scribbles

This book is about the realization of

I-thought-bird-was-part-of-me-but-I-was-part-of-bird sequence

It’s a delayed record of such a sequence

The promise of being freed from the book and

being able to step off the paper-thin railing

if I write everything down

It’s the delayed record of my regret

Bird's Repetition

All the stories bird tells perched on the treetop are about me

Nothing about the rumors of my lies, my thefts and such but

something ordinary like how I was born and died

Bird talks only about me even when I tell it to stop or change the topic

It’s always the same story like the sound of the high heels of the woman,

walking around in the same pair all her life

This is why I have a bird that I want to break

Like a poet who buys a ream of A4 paper

and crumples the sheets one by one and tosses them

I have a bird I want to break

When I crumple up my poems that are like

the family members inside a mirror in front of me

I can hear the stories of fluttering birds

“You were born and died”

Then I say, You scissormouths

and go buy a paper shredder

to shred every poetry book of mine

But later, when I opened up the shredder

a flock of birds was sitting inside, talking about me as if reading line by line

Moreover, each bird had a different face

and the hens talked about me even while sitting on their eggs

They didn’t care to fly off

Instead, they clustered under the peanut tree and talked about me

like peanuts under the ground

So, I said to them, enough of telling the same old story of how I was born

and died

How about something else?

For instance, how about the fact that I always wear the same high heels

to work and back

but when I’m under the same tree at the same park

I always dance a waltz

And do several movements of embracing the moon

But they replied,

You were born inside bird

Not opposite of that

You died inside bird

Not opposite of that

You were born and died

Don’t Fly in This Country

Daddy, I was born here, yet I’m told to escape

I’ve lived here all my life, but I’m not allowed anymore

This nation is out looking for me

Borders are sealed

I’m told to get out

All of its territory rejects my footprint

They all know my face

They’ll kill me if I breathe

I’m not allowed to cry

Daddy, I escape into the water

My body floats when I close my eyes

Nothing but water

Daddy, Look! I get even thirstier under water, that’s why my body floats up

Look, I can even lie down on walls

I can also walk on ceilings

I roll up my body and fly

Books fall from my shelves

My dishes fly away

My house leans sideways

Time drags its feet slowly along where water pressure is high

A thousand-year-old turtle crawls out from under my bed

Here, bird walks with its ten fingers over its face

worried that someone might recognize it and point a finger at it

worried that its body might float ridiculously in front of people

Daddy, When I lower my head and quietly fly down to the bottom of the

building

my teacher sitting at the bottom of the ocean says,

It’s so difficult to die

Go up toward the light, go higher

Push up your butt!

Sun sits on top of sleep like a yellow houseboat

and a lonely diver’s tears well up from his chest

You are bound to lose your shoes in water

You are bound to lose your cell phone

You are bound to lose your passport

Right now, I’m ill up in the air

I’m deathly ill, unbearably thirsty

I want to open my eyes

but my nation says, Wait till I catch you!

All of its territory rejects my feet

Translated from the Korean by Don Mee Choi.

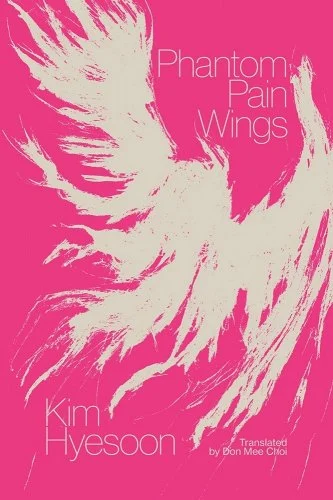

“Bird’s Poetry Book,” “Bird’s Repetition,” and “Don't Fly in This Country” from Phantom Pain Wings by Kim Hyesoon, translated by Don Mee Choi. Copyright © 2019 by Kim Hyesoon. Translation and copyright © 2023 by Don Mee Choi. Reprinted with the permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.

Mirrors of Ruin: Kim Hyesoon, Don Mee Choi, and the Reflection of Twoness in Poetry and Translation

Poet Kim Hyesoon’s work is a mesmerizing amalgamation of ghostly essence, vivid imagination, and profound interpretation of death, showcasing the world filled with unnerving devastations, resistances, and dreams. Her visions transcend mere observations, serving as transformative mirrors reflecting her experiences and the encompassing world. Kim's are lines of personal lamentations sung against the backdrop of the restrictive societal structures of South Korea and the expansive, global world she has endured.

Her poetry envelops the reader in a sensory overflow, granting a glimpse into harsh realities both individual and collective, accessible even to those unacquainted with Korean culture and history: the enduring scars of the Korean War, the eras of U.S.-supported military dictatorships, ongoing inequities inflicted on women, marginalization of divergent gender and sexual identities, and the battle for human dignity in a time dominated by the caprices of capital and unrestrained technological dystopia.

Kim Hyesoon’s rich, complex metaphors and imagery unfold like a pair of magnificent wings, transforming anguish and oppression into a vivacious, mesmerizing flight, leading readers into an intricate dance with shadows, inviting them to witness the metamorphosis of the soul. Her words, ultimately, craft the portrait of a world unbounded by time and space, where the ephemeral and eternal coalesce, culminating in a haunting symphony, oscillating between realms seen and unseen, known and unknown.

And her translator, Poet Don Mee Choi, plays an essential role in rendering Kim's visions in English. Together, they unravel a layered perspective of South Korea’s haunting history and its place in the world, challenging conventional perceptions of language and reality.

Don Mee Choi, acclaimed for translating Korean poetry and championing experimental poetics, interprets Kim’s works and brings forth Kim’s unique self throughout many volumes of poetry in translation, including the latest titled Phantom Pain Wings (New Directions, 2023).

Kim Hyesoon’s Phantom Pain Wings is arguably a 'I Do Bird’ collection: “I-do-bird” is a phrase that appears in the very first poem of the book which says, “This book is not really a book / It’s an I-do-bird sequence.” It is Don Mee’s translation of Kim Hyesoon’s Korean line “새하는” into English. What kind of movement does 'I Do Bird' imply? The juxtaposition of the noun 'bird' and the predicate 'to do,' denoting action or effect, perhaps feels strange at first. Sentences like 'a bird does something,' where the bird is the subject, or 'become a bird' or even 'how to do a bird' would be considered more natural by many English speakers. However, in the Korean original, “새하는,” it is also not clear whether the 'bird' is the subject or the object. There is an ambiguity, where the position of 'bird' could either be subject or object or both. Kim Hyesoon’s precisely crafted phrase makes this sentence break down the rigid grammatical boundaries between subject and object, agent and entity. This powerful and captivating 'performative sentence,' which erases the hierarchy between human and animal or subject and object, is the driving mechanism that penetrates Phantom Pain Wings.

In the phrase “I Do Bird," we also witness Don Mee Choi’s translation methodology in action as it captures the rhythm, the intrigue, and the utter peculiarity of the original. Its catchy strangeness is almost revolutionary (dare I say, there are echoes of ‘Just Do it’ here) — challenging the conventions of the English language. Even though “I” and “Bird” seems to have returned subject and object to their places, the positioning of “do” in between the two disrupts that relationship much like in the original, while maintaining that mercurial three-syllable rhythm: “새하는”, “I-do-bird.” As Joyelle McSweeney said in her recent review of Phantom Pain Wings, “ “I-do-bird” indicates directions of flight that are both sublime and bodily, physically inside and at the same time spatially or spiritually beyond.”

I also believe that in these kind of translations Choi seeks to peel off the English language. By "peeling off ", I mean that a translation reenacts the quirks of the original, without trying to streamline or simplify. This technique renews the target language, in this case English, and brings forth a fresh perspective, free from the corruptions imposed by dominant powers.

I say “the corruptions imposed by dominant powers” because Don Mee Choi's perspective on translation also speaks to the deeper political implications of language and identity, which she wrote about in her pamphlet “Translation is a Mode = Translation is an Anti-Colonial Mode”. By bringing forth the idea of language corruption and American imperialism's effects on Korea, Don Mee explores the complex dynamics between dominant and marginalized cultures. The American influence, once an oppressive force, is now intricately linked with Korea's linguistic and cultural identity.

Thus, in translating Korean poetry into English, the act goes beyond merely crossing linguistic borders. It is about redefining those borders, understanding the shared histories, and witnessing how English and Korean now mirror each other, opens deep gaping holes on each other’s surfaces.

Kim Hyesoon and Don Mee Choi, embracing the twoness of mirrors facing one another, shows the art of translation as an aggregate, a collective enunciation. Kim and Choi’s works are not about crossing borders or defining national literature; instead, they are reflections of collective, intertwined destinies and experiences, mirrors revealing the ruin within.

And sometimes, when we confront these reflections, we understand our collective self, our shared ruins, and the profound truths they reveal. Through this mirrored reflection of twoness, Kim Hyesoon and Don Mee Choi invite readers to traverse the realms of devastation and transformation, to see the world and themselves through the facing mirrors of poetry and translation.

So, as we delve deeper into this poetic realm, let's not just attempt to decipher or relate. Let's experience it, live it, feel it. Let the bird fly into the gaping holes on the surfaces of mirrors facing one another. As Kim Hyesoon and Don Mee suggest, let's not just look at the bird; let's "do bird."

*

These remarks were adapted from an introduction at to the T.S. Eliot Memorial Reading with Kim Hyesoon with Don Mee Choi for Harvard University's Woodbery Poetry Room on October 2, 2023.

Jack Jung studied at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he was a Truman Capote Fellow. He is a co-translator of Yi Sang: Selected Works (Wave Books 2020), the winner of 2021 MLA Prize for a Translation of Literary Work. His poetry and translations have been published in Washington Square Review, Bennington Review, BOMB Magazine, The Paris Review, Poetry Magazine, Chicago Review, Guernica, The Margins, Denver Quarterly, Poetry Northwest, and elsewhere. He teaches at Davidson College.

Kim Hyesoon, one of the most influential contemporary poets in South Korea, is the author of several books of poetry and essays. She has received many awards for her poetry, including the 2019 International Griffin Poetry Prize for Autobiography of Death (New Directions, 2018) and the prestigious Samsung Ho-Am Prize in 2022. Besides English, Kim’s work has been translated into Chinese, Danish, French, German, Japanese, Spanish, and Swedish