In Their Own Words

Yuki Tanaka on “Aubade”

I sit on a chair and the chair touches me back.

According to my chair, I have two hips

and bones inside them hard as peach pits.

The femurs connected to the pelvis

lead to the kneecaps. I have kneecaps.

In the ancient past of my village, people used them

as drinking cups: a boy sipping sake

from the kneecap of grandfather,

whose kneecap is bigger than grandmother’s.

She helps her son detach the kneecap from the leg

and wash it in the stream. White of the kneecap,

she thinks, is trembling like a moon.

Funny it smells sweeter than the knee of the man

she remembers. When he was alive,

he wasn’t much of a man—thin, boneless,

his shoulder soft as a berry-bearing ivy.

Funny he seems more alive now,

this trembling bone under the cold water.

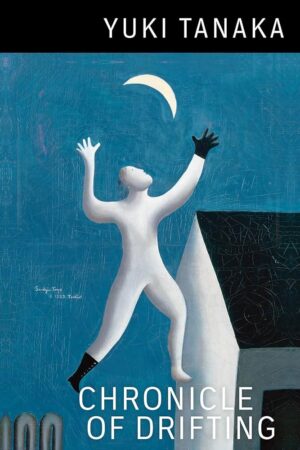

Reprinted from Chronicle of Drifting (Copper Canyon Press, 2025) with the permission of the poet.

On “Aubade”

“Aubade” is part of my first full-length poetry collection, Chronicle of Drifting. The book as a whole explores a shifting sense of self—its fluidity—against the backdrop of relocation and displacement. Throughout the collection, I move from speaker to speaker, mirroring this fluidity—sometimes a mythical weasel from Japanese folklore, sometimes a flâneur in Tokyo, sometimes a village mermaid.

With “Aubade,” I wanted to resist this tendency. Instead of putting on another persona, I began with myself in my most immediate surroundings—sitting on a chair, trying to write a poem. I focused on the sensation of my hips pressing into the seat, which made me conscious of my hip bones, thigh bones, and knee caps. By tracing my bone structure one by one, I tried to ground myself fully in the present moment.

But as I wrote, my mind drifted to an imaginary scene: a grandmother and her son washing the bones of a grandfather in a river. The scene was inspired by the Japanese Buddhist legend of Sanzu no Kawa, the river the dead must cross to enter the afterlife, much like the River Styx in Greek mythology. I had started alone in my room, writing; then somehow, I found myself in a mythic, ancestral, and communal space, one that feels emblematic of Chronicle of Drifting.

The title “Aubade” evokes, then departs from Philip Larkin’s poem of the same title, which places its speaker in total isolation from any community. Traditionally, an aubade is a love poem—think of Romeo and Juliet’s famous exchange about the nightingale and the lark—where lovers must part at dawn. Larkin subverts this by making his speaker loveless and alone: “I work all day, and get half-drunk at night. / Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.” I once knew the opening stanza by heart, and I suspect that Larkin’s iambic pentameter and declarative syntax shaped my first line: “I sit on a chair and the chair touches me back.” Unlike Larkin’s speaker, my speaker is saved from solitude, ending up with others, however imaginary.

Looking back, this poem feels unusually autobiographical. I wrote it during a difficult period, out of intense self-hatred. I now see how the speaker’s identification with the dead grandfather reflects that state of mind. But the poem, in the act of writing, took me elsewhere. The image of one person washing another’s bones became an act of tenderness, not just for the grandfather, but for the speaker. And in that, for myself.