New American Poets

New American Poets: Farid Matuk

Hollywood

for Zoila Matuk

Why shouldn't I take your pills

you've got the hospice Percocet all day

but it feels bad now to play fast and loose–

normally that lane in Kabul would be thick

with schoolgirls

but the Taliban came through

and you've got lumps

in your neck.

I'd like to go piss outside

to affirm life but Dallas is

everywhere a street with cars

always coming by.

President Karzai is not afraid, BBC says

I don't know why not–

there's opium growing over there

and the field surgeons are working hard.

El Paso in 98 degrees below

I'm coming to see you

I worry

the pilot is drunk, will

push us into the sand

because magic is sympathetic

and I watched a show about

plane crashes last night.

A girl calls out the things

she sees from the plane window

makes it all

as normal as the 300

Mexicans lynched

each year

down there between 1910 and 1920

I think before

ladies with smokes

had come a

long way

at all

–those times

the beginning

of cute

haircuts.

Now it's Phoenix

down there

and the guys behind me

are talking golf

and paradise

and buddies.

I'm obsessed

with marking my age

and my times–

I tell you it was like this:

I never cared for Kurt Cobain

shoe gazer

rich asshole

and I'm still not

a good friend

to suicide cases

Jesus, you don't see

Phoenix

killing itself

even

with the weight

of all its misting

tubes. I don't know

I guess there's

as much tenderness

in this plane

as bloodlust.

The big walrus of a man

tosses pretzels

to his little boy.

I keep telling Susan

we should adopt.

I want an eight-year-old

a cute one

maybe black Irish

with freckles under

shiny black hair

and green eyes

learning to track us

across the room.

It'd be great

to put our arms around

a part-grown orphan

and save ourselves

all that time.

Home again

I hang up the phone.

You keep throwing up.

I read a line

to the dog

who listens

then turns to mauling

his favorite pillow

piling stuffing, big polyester balls

around the room.

I wanted to make friends cry

maybe that's what Scott said

about his reading

but he didn't write anything new

and neither did I.

I should pull the pillow away and give the dog his rubber bone.

When it's good I see

all the parts of the poem

levitate at once

into a constellation

but these days I just

want a maid

and someone to mix

the strings in the background.

I kiss the dog

and smell spit

over hair

warm with blood and cells

in commerce.

So what's special

about people

then? I tried

one of your

morphine pills

and just cramped

and slept.

It was the opposite

of hip-hop

the windows

down speeding

up Central Expressway

and knowing

I just

got a retirement

account. Either

way I think

it's death people

bring but I

don't know how

tonight.

I know I can

say striped paint

I know there is

Plains grass

opening and rejoining itself

in the wind,

desert Mohave stones

various dirts do glint.

Tell me about the furniture

in your parents' house–

none of it was yellow

and there was only

one dog named friend.

Young ladies don't wear fur

at the table, in other words

sit up and the mountain

never blew and soldiers

never walked the streets

but there was the convent

and that put a little quiet

into the trees.

I'll tell you

the neighbors here in Dallas have four

crepe myrtles in their yard

and their canopies have grown together

into one shade, oh

it doesn't matter what

a crepe myrtle

is, but their bark is smooth.

You never met my dog but his

tendons are very long

and I bet they wouldn't tire

if we had to walk all day

up the

Goodnight

Loving Trail

to its source

–Wyoming.

Tell me where you're from

and I'll place you in the parking lot

my brothers and I will dress

in grasses and the steady passing

of the cars will go dim and

we will be a wall of grass you face.

Let's say you were from Hollywood

the furniture in your kitchen was yellow

so we said Hollywood without end

until it meant nothing and your home

was in our voice.

Your father was a stern man

there was a dog named friend

cars don't stop.

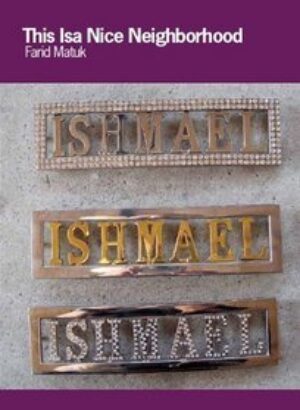

From This Isa Nice Neighborhood with the permission of the Author. All rights reserved.

Introduction to the work of Farid Matuk

Geoffrey G. O'Brien

Farid Matuk's This Isa Nice Neighborhood takes its idiosyncratically compounded title from a never-executed public art commission in San Francisco; the project would have arched that phrase in neon at the former site of a Filipino community and glowed parts of it simultaneously in Spanish and Chinese towards the Mission District and Chinatown. It's a canny choice for a poetry that seeks to occupy every available subject-position in relation to an event. Early in the book we encounter two consecutive poems titled "Talk" (there are many repeated titles across the collection) that describe the same melancholy self-interested exchange in Sicily between a North African teenager and a group of Italians, the first poem beginning "I am Moroccan today" and the second "I am Sicilian today." Like the simultaneously glowing phrases projected at neighborhoods, Matuk's I and today wander through perceiving centers and their inflections by class, race, and country, and don't do so to isolate some corporate human essence, but to track the interactions of different persons and the tragic and gratifying outcomes of those encounters, the "History As a War of Poses" as another early poem has it. That wandering through minds multiply foreign to each other has its counterpart in Matuk's extraordinary comfort with moving from subject to unobviously related subject as he moves between lines and stanzas. It's a poetry that softens the difference between non sequitur and entailment:

He wanted to lift the particular edges of their wishes to that dusty light

and witness the glint together, and wonder

and be so joined as he felt himself to be

with the wife slightly standing

and the reporter barely there.

And yet, there is nothing of this by the sea

("Maybe Go to the Sea")

This empathic imagination that, beside the rolling sameness and difference of the waves, conjures the execution of a thief and his mourning wife half a world away, is typical of Matuk. He will not sacrifice the glory of the incessant ocean, the mutation's of sunset's internal differences, nor any affectionate, jaunty declarations of love for his partner Susan and their dog, but he will not pretend those avowals and their objects don't happen in a world that has also permitted countless lynchings and fatal border-crossings and hate speech—all those waves too are part of an ongoing singable tally. The book ends with a series of "Tallying Song[s]," a phrase borrowed from Whitman's "When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom'd," and like Whitman, that earlier poet of ecstatic and solemn inventories of difference, Matuk seeks to "accommodate the earth" in all its social and phenomenal variety, opportunity, and damage. It's why a poem about Richard Pryor and race relations can end "Birds in song / spit gold ropes"—the poet's gaze can make "thin relation" of anything because "everything / happens beneath the cover /of something else, something prettier / now there are Arab African boys everywhere" and even the words "is" and "a" can unite to form a new neighborhood.

Statement

Farid Matuk

Kobena Mercer reckoned critically with his desire for black men some time after taking to task Robert Mapplethorpe's photographs of black male bodies, bodies Mercer saw as kin. He came to acknowledge a partial identity with Mapplethorpe's gaze, noting that "[i]n contrast to the claims of academic deconstruction, the moment of undecidability is rarely experienced as a purely textual event; rather it is the point where politics and the contestation of power are felt at their most intense."[i] It's a revision of Keats's negative capability from "when a man is capable of being in uncertainties" to "being uncertainties," a shift from incongruous ideas to incongruous subjectivity. So we are doubled and estranged even while we are made available to shared histories. No news here for poets, but I like Mercer's articulation because it reminds me that the terrain of awareness, of subjectivity, is politicized and open to resistance. Rather than try to literalize the indeterminacy of language, I take Mercer's suggestion that language is being historicized and coded by its communities of reception, occurring in tandem with context, with audience, and so with rhetoric. The possibility of play in this process hooks me into poetry.

Dale Smith and Jeffrey Walker talk about a "transpersonal lyric" that allows for such variance and play. They situate the lyric in ancient Greek rhetoric to suggest lyric poetry "makes arguments" and runs counter to romantic-modern notions that perceive the lyric as a "state of feeling" or unified subjectivity.[ii] They emphasize ceremonial staging, with its attendant dynamic between an unstable speaker and audience, and so edge the lyric toward performance. Or maybe more precisely, they locate lyric's potential to stage arguments in the chasm between poem and reader. I want the poem to be an argument that advances through a protean range of illocutionary gestures and ellipses, activating assumptions and responses for readers that exceed anything the poem or poet could anticipate.

My teacher, the late Lindon Barrett claimed, "the market depends foremost on simplifying and exploiting virtually all orders of the imagination."[iii] Many contemporaries I admire, Susan Briante and Rosa Alcalá, to name only two, train the formidable intelligence of their poems on the imperative of frantic capital exchange that marks our moment. While I want the poem to be an argument, at the same time I try to respond to Barrett by making with the lyric a space where the vagrant imagination can range. In this I've found help in poets' journals as much as in poems, the notebooks of Hopkins, the travel journals of Tu Fu, Schuyler's diaries, but also in poems that seem committed to composition by receptive attention rather than willful intention, the work of Joanne Kyger and Philip Whalen, for example. What I am trying to say, so as to approach a ground floor of my poetics here, is that part of what I want to know in a poem is how the poet got over, from one precarious moment of being in the world to the next, and how the poem can help open spaces for the imagination that are fugitive but resistant, and maybe free.

[i] Mercer, Kobena. Welcome to the Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies. New York: Routledge, 1994.

[ii] Smith, Dale. "The Romantic-Modern Lyric: Poetry for the Non-Poet." Poetry Project Newsletter 206 (2006): 21-22. Jacket. July 2006. Web. .

[iii] Barrett, Lindon. "Black Men in the Mix: Badboys, Heroes, Sequins, and Dennis Rodman." Callaloo 20.1 (1997): 106-26.