In Their Own Words

Elisa Gabbert on “Jack always feels like someone is watching.”

Jack always feels like someone is watching.

So we turn it into a game.

We do things for their benefit.

We invent a code name for suicide,

"The Attractive Option,"

and refer to it often.

Emerson said,

For every minute you are angry

you lose sixty seconds of happiness.

But he also said, The purpose of life

is not to be happy.

I say to Jack,

Life makes it impossible

not to waste your life.

Speech is a charade, of course,

but sometimes I think things

for their benefit. An idea

is part of the persona.

I'm interested in the point

where the game crosses over,

where he is laughing

and I am afraid.

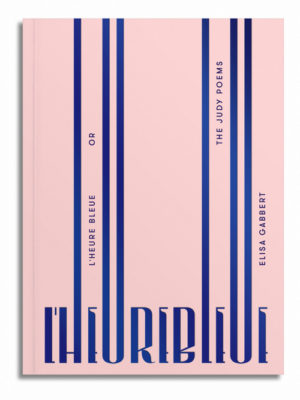

From L'Heure Bleue, Or The Judy Poems (Black Ocean, 2016). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Jack always feels like someone is watching."

Several years ago my husband John and our friend Aaron decided to stage a small production of the play The Designated Mourner by Wallace Shawn. Without having read the play, I agreed to play the part of Judy; Aaron would play Jack, Judy's husband, and John would direct.

The following night I started reading the play, and within a few pages I had regrets; Judy is a nearly impossible part. (Even Miranda Richardson, in the 1997 movie, doesn't quite pull it off.) How was I, a poet and not an actress, going to do it?

Since we all had other work to do, we rehearsed only once per week—but kept up rehearsals for over a year, finally doing the play around seven or eight times in private settings, classrooms and living rooms. I was shocked to discover that I could act, that I could even memorize my lines. (It's a two-and-a-half-hour play, with only two real characters.) What magic! You can just decide to do something, then do it.

After spending so much time in Judy's head, trying to understand this impossible, unplayable character I didn't like, I found I wasn't ready to let her go. Meanwhile, I must have been tired of myself, looking for ways to transform my own experience into something I could write about.

Then one night, at a poetry reading, some lines came into my head. They were in Judy's voice. Oh, I thought: Of course. I should write as Judy.

As I wrote the poems that turned into L'Heure Bleue, I felt a kind of triangulation happening—the woman in the poems was not quite Judy and not quite me, but a third person. The Jack in the poems is not the Jack in the play, but another Jack, subtly inflected (or infected) by Aaron and by my own husband. The setting of the poems is not the play's setting (which is never specified, but feels like a cross between New York and Pinochet's Chile) but some other imaginary space, an impossible country with an apartment that looks like mine, with Denver parks and Manhattan streets and South American dogs. When Judy or Jack didn't have enough to offer me, I'd supplement them with details from my own life.

I wrote most of this particular poem while sitting in the waiting area of an emergency room. I remember scratching it out in the little green notebook I carry. I had been thinking about surveillance—which is particularly relevant to Jack and Judy, who are living under a totalitarian regime, and are targets in part because Judy's father is a well-known dissenter who published a book of political essays in his youth. The situation gets more and more dangerous, eventually destroying Jack's mind and their marriage.

I was also, as ever, thinking about happiness; my husband had a strange condition which was driving him almost mad—causing dizziness and sudden spells of debilitating vertigo and hearing loss that changed by the hour. It's part of the reason we stopped doing the play. He was missing tons of work and losing sleep, kept awake by roaring, grinding tinnitus and a terror that any morning he might wake up totally deaf. We were both miserable with fear and anxiety. But I filtered those emotions through Judy, who is always cool and distant, who sees her own emotions through a thin film of irony, even judgment.

I remember finding the two Emerson quotes in a list on Goodreads. (Emerson appears once more in the book, quoted by Jack: "Truth is shrill as a fife." I am not sure why; I was not reading Emerson.) The lines that Judy speaks to Jack are mine: I tweeted them once. This is also one of several poems in the book that reference the process of the book's creation. Who is Judy "thinking things" for, the government or me? I like to think of my Judy as aware of me, her semi-creator, a presence that she can sense watching. The third person.