In Their Own Words

Margaret Ross’s “A Timeshare”

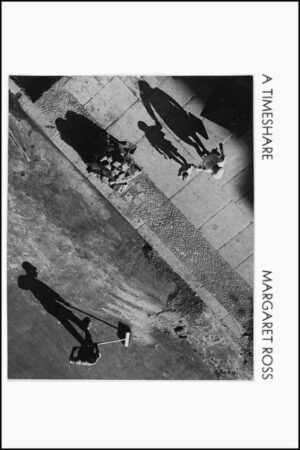

A Timeshare

Five o'clock again in the rented living

room. Nothing wrong. Heliotrope continuing

to fade into upholstery. Buttons pressing back

against the back of the couch make the surface

cave, just decorative, faint garden stamped

on a cotton throw. And that the world. Yes no. Yes though

if there's such a thing as time at all I never saw it

move and if that's so then what am I

afraid of? I hung a muslin curtain to prove

breeze, a nimble petal, tall fluctuating seraphim

who keeps watch over me. Q: What are you

doing down there in the

there in the meantime? X: All day

I am an orchard at midday when the stunned air

pauses, bronze and stupid, terse with flies. Don't lie. I'm

in the living room. Seconds dropping

from the faucet to the metal bed

of the sink: this is your one

now this is, now late, nobody waits for thee

on the greeny moor where I was

lain all stuck with yew, or the Q: Did we

outgrow our dream of a point repaired to when alone?

Some to the landfill, some to the promontory,

each with a small smooth stone tapping soft

on his chest or clicking against his teeth

when on his tongue. Once you thought you would learn

what to do with yourself by yourself. Once the stakes

flush high as a view from the beautiful

private plane, all persons disappear

and he alone looks down on freeways

embroidering the vacant earth. It was still early

in my life. X: Go along. Touch

your eye. Do you know how to do

that thing of whispering a fact repeatedly

until it stops being true? Returned

to this apartment after

being gone a while to find

everything replaced with replicas, identically

arranged: the cedar desk had the same false front

as before and fitted with

the same brass garland handle

still unable to pull out a drawer because it is

no drawer. That was the soul. Communicating

chambers of my third-story home

string a sentence furnished with secondhand

pieces. White hooded lamps are nurse to me

all night when I can snap space open

like a parachute, make the walls up

when I lived out a summer with a blind man

by the sea, he kept a steady squint, I closed

my eyes, it was still early then

in my brief life, evenings, every morning

at the folding table painting his toast black

with Marmite, once she was me

we took turns for the bed, a room with

everything white except the book spines

makes you feel the good kind of dead, when

is it, someone's kid downstairs

leans on the bell again, lived winters half

an hour away or seven minutes

on the red line, times he had me

scissor bracken stalks to stanch the mud floor

of the animal shed, from space the night's a hammock

swinging gently out across our Earth, each fall

slushed over, birdcalls' tiny screws

creaking shut your mind

when I used my fingernail to scrape

white tallies on my naked ankle then

think of the long trip home.

You're already home. All the loyal

idiot details know what to do to

stay believable but you

you who sit and let the light rust

reddening all around you waiting for

anyone to come and tell you to

get up get up nobody is.

From A Timeshare (Omnidawn, 2015). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "A Timeshare"

When I think of the soul, I think of furniture. The two occupy a similar place in life, so domestic as to be mostly ignored and thereby capable of seeming totally surprising and alien when looked at closely. They're the contours around which experience forms, the surfaces on which we write, think, work, fuck, eat, read, sleep. To trace those contours is to silhouette being.

I wrote this after reading Alphabet, Inger Christensen's great poem about the relationship of the one to the many and how it plays out through nature, history, community, the state, the future. Her form is the wisest map of time I know. An abecedarian where each new section is the length of the prior two combined, it's shaped by two ideas of order: the Latin alphabet (which is, of course, a human construct, arbitrary and beloved) and the Fibonacci sequence (which occurs naturally in plant and animal bodies). So the formal progression of Christensen's poem—its sense of time—is as much an invention of the human mind as something involuntary, biological.

I wanted to write poems that had the same feel for intersecting systems and for the multiple, entangled nature of a life lived between them. To my mind that meant scale shifts. Each poem is set in a single scene from which the feeling comes, but truly seeing that scene means seeing its ties to other times and places, hearing echoed voices not the speaker's: the past inscribed in the present's gestures, the traces everywhere of other lives. The ambition is visceral plurality via image and music.

There's a line of Bishop's that's stuck in my ear: "Everything only connected by 'and' and 'and.'" The words describe the tenuous connections between things, but the sound of the line—that triple punch of the 'and'—belies semantics and finds real strength in those connections. In my own poem, I consider the italicized section a counterpoint to the stanzas around it. It presents an alternate speed of life, another way to add up experience. So the poem conveys different means of inhabiting time. Its title is porous. The plural lives in the singular: a timeshare is premised on the idea of many people taking turns. The word itself seems translucent. Behind its literal definition can be heard a broader resonance. We recognize space is a shared resource but it's as true of time. You can feel yourself a tenant of the atoms you consist of, these structures that used to house other selves and will, in a few decades, house others still.