Q & A: American Poetry

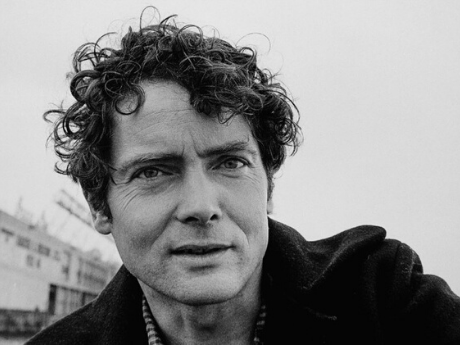

Q & A American Poetry: W.S. Merwin

Before I was twenty I used to ponder, sometimes, what it meant to be an American poet, what would make a poet, meaning me, an American poet. Some of the senior figures to whom I looked up at the beginning had considered that question with urgency and pertinence—Eliot and Pound while becoming (the word is used far less frequently now) expatriates at a time when that seemed to be regarded, by many Americans, as a kind of deviant behavior. Williams had labored tirelessly to establish a poetry rooted in ordinary, and local, American urban life. Frost and Marianne Moore did the same thing without following it so self-consciously as a program. They seemed to have settled something. And later, the generation before mine managed to continue as though the matter did not have to be settled all over again. They assumed that they not only had but were inseparable from an American tradition, and they were sure enough of that not to have to defend themselves against England and worry about which side of the Atlantic they were on when they were writing. Lowell and Roethke, Jarrell and Berryman, all spent time in Europe, in England and Ireland, and wrote there, without seeming to feel that it required any soul-searching about whether or not they were still honest-to-goodness American poets. By the time I was into my twenties—and in Europe—the question had long since ceased to be one, for me, though in fact I wanted to get back to the States, and to life in the States and the language there.

I certainly do not think of the tradition of American poetry as simply a homogenized addition to the English tradition. I feel that we are lucky to inherit it with a particular closeness, but that we also inherit the whole tradition of poetry in the language. I don't think there is much to be gained by self-conscious efforts to write some kind of genuine American poetry. If American poets write poems they will be that. We have what might be thought of as a gene pool of poetry by now, and certainly our own experience, and writing out of the latter is part of our recognition of it. When I read poems I am hoping to find poetry, though I might have trouble defining that. But only if I do find it am I likely to be interested in the writer's nationality or other distinguishing characteristics. And I think that setting up checkpoints of political correctness for poetry is as destructive and inappropriate as any other kind of censorship of the arts and is following an old and dismal pattern.

Published 1999.