Tributes

Garrett Caples on Philip Lamantia

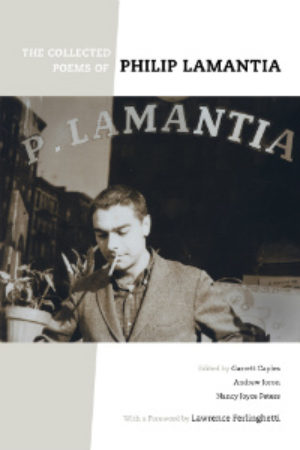

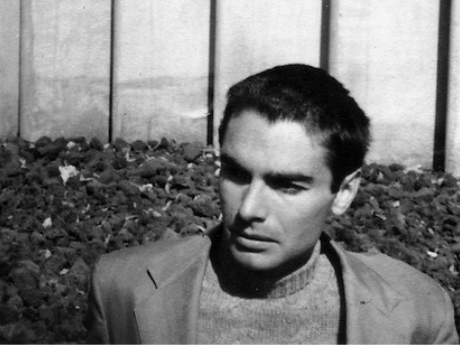

When we were working on the just-published Collected Poems of Philip Lamantia (University of California, 2013), Andrew Joron and I visited Michael McClure to talk about their friendship at the turn of the '60s. And we were both forcibly struck by McClure's remark, apropos the readers at the famous Six Gallery reading in 1955, "We all looked to Philip," pointing out that, going into the event—aside from Kenneth Rexroth, the evening's emcee—Lamantia was by far the most famous and experienced poet, the only one with a book (Erotic Poems [Bern Porter, 1946]), not to mention extensive magazine and journal publication, from View in the early '40s to the New Directions annual in the early '50s. Even as a friend and partisan, I was taken aback by this perspective, but it makes sense. In 1963, having eclipsed Philip's fame by many magnitudes, Allen Ginsberg would defend Lamantia's Destroyed Works (Auerhahn, 1962) against an ill-informed attack by Richard Howard in the pages of Poetry by invoking this period of wider influence:

His interest in techniques of surreal composition notoriously antedates mine and surpasses my practice in a quality of untouched-ness, nervous scattering, street moment purity—his imagination zapping in all directions of vision at once in a cafeteria—prosodaic hesitancies and speedballs—the impatience, petulance, unhesitant declaration, machinegunning at mirrors nakedly—that make his line his mantric own.

Since I'm cited as stylistic authority I authoritatively declare Lamantia an American original, sooth-sayer even as Poe, genius in the language of Whitman, native companion and teacher to myself. "And for years I have been absorbed in contemplation of the golden roseate auricular gong-tongue emanating from his black and curly skull. Why not." Says Philip Whalen, and many poets his admirers Michael McClure and Robert Creeley others have spoken—[1]

Not content to implicate himself and fellow Six Gallerists McClure and Whalen, Ginsberg also reaches for Creeley, knowing this name will ultimately carry the most weight with 1963 readers of Poetry. And naturally Ginsberg invokes the surrealism Lamantia is best-known for, the rapid flow of automatic imagery in his early work that certainly influenced the "the best minds" litany of part one of "Howl" and reemerges with a vengeance in Destroyed Works.

This insistence on the originality of Lamantia's "mantric" line is well-taken. Consider, for example, an extract of a piece from his earliest surrealist period (1943-45) like "To You Henry Miller of the Orchestra the Mirror the Revolver and of the Stars of Stars." The level of sustained, furious invention over the course of this 73-line poem—written before Philip turned 18—is quite unlike anything being written in 1940s American poetry:

Insidiously walking down the spacious hallway

where red bandanas wave hello

my sweet bucket of excrement crisscrosses you all

the way

Under my foot at noon

when we have bitten glass walls

just when my head is swimming in a pyramid in Mexico

just at that time you crawl forth

reading a parable

for no reason at all[2]

This is true surrealist imagery, surprising, irrational, ultimately unseeable; what could it mean to say the "sweet bucket of excrement" "crisscrosses" Miller? How could this second stanza occur "under" Lamantia's "foot," or what sense can we make of the temporalities implied by "noon" and "just when"? Among poets working in a surrealist idiom in English at the time—Charles Henri Ford, Eduoard Roditi, Parker Tyler, David Gascoyne, even William Carlos Williams when he tried it—no one achieved anything like the fluency of Lamantia's automatism. His achievement in American poetry is as singular as Jimi Hendrix's on guitar: he's unlike what came before and he's different from yet crucial to what comes after.

Though I'd quoted on more than one occasion Rexroth's assertion that "a great deal of what has happened since in poetry was anticipated in the poetry Lamantia wrote before he was 21,"[3] I realized I hadn't fully believed it, inasmuch as I was discounting it for self-aggrandizement. What is understood here is that Rexroth, considering himself Lamantia's discoverer (false) and mentor (true), is the root of post-war American poetry. But hearing McClure's statement, and the way he said it, suddenly cast the proposition in a whole new light. That poets (in McClure's touching phrase) "looked to" Philip doesn't mean they were imitating him so much as he exerted an influence by being a peer who through his precocity already had a dozen years of published poetic activity under his belt, and was a direct, unmediated link to a prior European avant-garde for the poets now variously classed as the San Francisco Renaissance and the Beat Generation. He was one of them, yet he had rubbed shoulders with high modernism, from exiles like André Breton to returning expats like Henry Miller. He "anticipated" "a great deal" of his later contemporaries insofar as his surrealism pointed to a more spontaneous poetics than the likes of Pound, Eliot, Williams, or Hart Crane had to offer. Of the poets of the New American Poetry generation, Lamantia struck the first blow.

To You Henry Miller of the Orchestra the Mirror

the Revolver and of the Stars of Stars

On entering the house

on the street suffering from heartaches

I encounter you

a little to the right of the parasol

a little over the phonograph record with yellow fans

a little like two dice and a hatchet

you mingle with women who have lost their wombs

in the smoke

Insidiously walking down the spacious hallway

where red bandanas wave hello

my sweet bucket of excrement crisscrosses you all the way

Under my foot at noon

when we have bitten glass walls

just when my head is swimming in a pyramid in Mexico

just at that time you crawl forth

reading a parable

for no reason at all

But pass away

the iron rust of your face wants love only love

not a smell of infested testicles

O what is this host of children anyway

it interrupts our hunting

the old women who are producing altars of morphine

So forever the windows shine at the top of your head

forever the madmen are excused from the dinner table

Wave goodbye

your friend is waiting for you

he is secreting a blue fluid from his ear

which spells out in the sky "es—o—ter—ic buddhism"

Don't worry rats hide in the night soil

where old men's beards grow as strong as a priest in the sun

with his cleanshaven face in gasoline

Forget me forget me tomorrow

the virgin will prove wholesome under the sea

Rain on her all the gorgeous animals

have them nestle close to her hymen

What I have related is written on the wall

you talk from the depths of this drunken vocabulary

What does this mean

what does anything mean

It is worth beating the floor of the palace

with your muscles

Oiled and soaked in the magic wines

your body will be preserved for the hawks

who love you dearly

from morning to midnight they remember you

and shower you with scented vapours

But until you regard yourself with suspicion

your attacks on the aerial child will not end

and dung will continue to fall over the child's lips

But wash your thighs

priceless in the prison cell

when you squeeze out the liquids of horses

A little too dry you cling to the building

and watch the mist shooting balls into the sky

But don't let the amphibious wife strangle you without

a nightgown

The police might suspect her of hiding in the thunder

where the gulls ride over the silk stockings you stole in Paris ten years ago

To raise a beard on your ear will take centuries

so release the wristwatch from your matchbox

and enter the plate where women ask no questions

The umbrella is alarmed

don't have it spring on you

with its platinum mouths

and hat of blood-ridden fur

It sings to the vile eggs in the garden

which silently creep into your lake to melt away

And as sweat pours from your eyes

to change into salt

the gates fashioned from your children's bones

are swung open

to release the telephone of cement

to disclose the statues walking at midnight

inducing you to fly into the rubber castles of the sun

Poems reprinted from The Collected Poems of Philip Lamantia, by Philip Lamantia, edited by Garrett Caples, Andrew Joron, and Nancy Joyce Peters, published by University of California Press. © 2013 by the Regents of the University of California.

* * *

[1] This letter is reproduced many places but I'm looking at it in Alastair Johnston's A Bibliography of the Auerhahn Press & Its Successor Dave Haselwood Books (Poltroon Press, 1976), p. 39.

[2] Philip Lamantia, The Collected Poems of Philip Lamantia (Berkeley: University of California, 2013), p. 27.

[3] Kenneth Rexroth, American Poetry in the Twentieth Century (NY: Herder and Herder, 1971), p. 165.