In Their Own Words

Cynthia Dewi Oka on “The Year of the Shoe”

A child, perhaps, one of many, sat, arms folded

at a desk painted the color of seafoam – also one

of many. The wood had not been sanded; often,

it splintered the sides of her hands as she lashed

slippery knots of alphabet around the pack of dogs

leaping from her throat. Afternoon fell in slats

upon her so that she was at once brown and yellow –

light crowded with the honking of cars, flies

and their notions of sovereignty, falling sanely

on the police who directed traffic to and from

the school, notorious for their sticks and the pigs

they shared their living rooms with. I say perhaps,

because it could be anyone in that country, during

that time, who had a secret, or was a secret, in that

there were many whose kidneys had not been

spilled in the fields, nor were found blue and tangled

among roots of the mangrove, nor like thunderheads,

vanished once the ditches were flooded, the streets

waist-deep in shit. Nothing was less remarkable

than that child, her waiting a pinky bone among

the rows of waiting, for an afternoon sticky

with papaya juice and tumbling into the leaves

like kites, her obedience no more than the other

obediences, which combined rendered a room of sixty

first-graders quieter than grass waiting for the spade.

Quiet was the price of a nation to call our own – every-

one knew this – and so she did not hear the bullets’

laughter in the spines of East Timorese girls, boys

clapped to dust in the red hands of the Santa Cruz

cemetery, no, the child’s memory of that year

was of the rock she felt in her shoe minutes

before dismissal, how she tried to ignore it,

how it bit back with its single tooth, so that at last

without full consideration of the consequence, she

slipped out her foot and reached down to turn the shoe

over. A small click where rock hit the floor, and

looking up, she met the gaze of her teacher, like lava

hardening or the night that stumbled in like a drunk

through the door of the shack, where she had once

visited with Mother to see that a teacher lived much

like the police, with pigs not for eating, but for breeding

and selling to keep the lamps lit. But a teacher’s words

were second only to Father’s, so that day she licked

the tips of the sentence like goat-meat: stand

on the bad foot, in front of the classroom, for one hour.

The child watched her friends peel away, like husks

and hair from a cob of corn until the rows were

fat with their absence, guilty knee trembling

under her weight. She would hear none of the hard

whispers between Teacher and Father, who soon enough

would take her home and lie her face-down

on the sheet with the faded pink and purple flowers,

to paint pink and purple flowers of his own on the backs

of her thighs with the zinc – zinging – of his belt. For this

was what it took to survive, a secret among secrets,

while whole islands burned and the sea watched,

remembering nothing, filling shoe after shoe

piling on its floor like toothless mouths

with its own quiet and ambition, that it should

be the first and the last, the only year there ever was.

Copyright © 2022 by Northwestern University. Published 2022 by TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved.

On “The Year of the Shoe“

From 1967 to 1998, Indonesia was ruled by the New Order regime, a dictatorship led by the nefariously brutal and corrupt Suharto. Formerly a military general, he was a key figure in the anti-Communist massacres that with documented American assistance took the lives of anywhere between 500,000 to 3 million people in my homeland.

I was born in 1985 in Bali, where an estimated 80,000 people, or 1 in 20 Balinese, were slaughtered during the purge. Of course, within the New Order’s ideological enclosure, bolstered by state propaganda, the absence of free elections, and military force, I had no idea until years later, when, like many diasporic Indonesians of my generation, I learned of these events through the writings of exiled or banned Indonesian writers, and various historical accounts by American and European scholars. To this day, the Indonesian government refuses to acknowledge or investigate the 1965 killings.

Being double minorities in Indonesia – Chinese Indonesians and Christians – my parents never spoke about their experiences of that time or dared to critique the New Order. Constituting only 1% of the population, Chinese Indonesians were already subjected to a wide range of discriminatory policies and frequently violently scapegoated in moments of national crisis. Meanwhile, church burnings were daily, unremarkable news while I was growing up.

As a child, I was taught to conceal these aspects of who I am from my peers and especially my teachers at school. I was expected to excel and certainly never to draw any disciplinary attention to myself. My name expresses my parents’ contradictory wishes: to simultaneously escape Indonesia and belong to it. Cynthia can easily travel in the English-speaking world, while Dewi is a common name for Indonesian girls, especially in Bali.

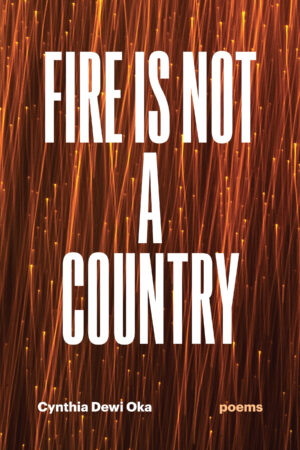

This poem, from my book, Fire Is Not a Country, considers the ways that history and practices of state rule come alive, replicating themselves in the small, yet defining arenas, of our lives. How they become embodied when they cannot be named, therefore thought about and potentially, contested. It describes an incident in which a six-year-old girl is punished for an innocuous gesture that troubles the strict requirement for obedience in an authoritarian society, first by her teacher, then by her father, though for different reasons. The teacher punishes her for disturbing the ten minutes of mandatory silence and stillness at the end of a school day (children do not learn either of these skills naturally), and her father punishes her for being punished by her teacher. Meanwhile, approximately 700 miles away, less than the distance between Philadelphia and Chicago, the Indonesian military is carrying out the Santa Cruz massacre, shooting at least 250 East Timorese pro-independence protesters, many of them teenagers. It is an absurd situation in which disempowered people – parents, teachers, the police – become primary vehicles by which authoritarian state power inscribes itself on a new generation of “citizens.”

I was not aware of the Santa Cruz massacre at the time it happened; I don’t remember seeing reports about it on the state news channel, which we watched diligently at 8PM every night. I made the connection only years later when as a college student in Canada (not because of a class syllabus, but because I was looking for books on Indonesian history in the campus resource center for student activists), I learned about the occupation of East Timor, that is, the way “post-colonial” Indonesia was repeating the savagery that its agents had absorbed from three hundred and fifty years of Dutch colonization and Japanese occupation during World War II.

It would take another decade for me to be able to write this poem. For years, long after he died, I believed that denying the violence I experienced so frequently as a child was a way of protecting my father, who had been even more disempowered as a Southeast Asian immigrant in a Western country. What that denial really did was confine me to pain; pain that limited my imagination, desire, art, relationship to myself and the world. This poem, though it hurt to make, was a step through silence and toward something else, some place innocence, not terror, may be the inheritance of all children.