In Their Own Words

Lightsey Darst on “Svalbard”

Light falls heavy as a full-grown fruit, dull gold, substantial.

I’m all old gold now, my quandaries and beliefs moot in this weather.

Hawklike, my daughter knows me deeper. Fearlessly she shows me

these absolutes we live in: my love, her needs. As if on an arctic journey under a dim star

I’m clutching a rattle box of seeds. Morning’s wheel will take me

where I can’t go. I follow her tumbling on my robe. I’ve lived

how I could, not how I couldn’t. Now how can I, dim alphabet, spell you?

It’s hard to have freedom within weather. Belief in anything is loss at last. Sweet girl,

I do not believe the soul survives. The whole survives as the arrow

flies. You shine like mother-of-pearl. Never more than a single dream

from night’s store. Rain finds its way through altered land, my land

finds its way through altered us as we find our way through

the midnight house. There’s no forecast for me but to follow you.

I’m lost, a root curled round diamond, groundless. What freedom.

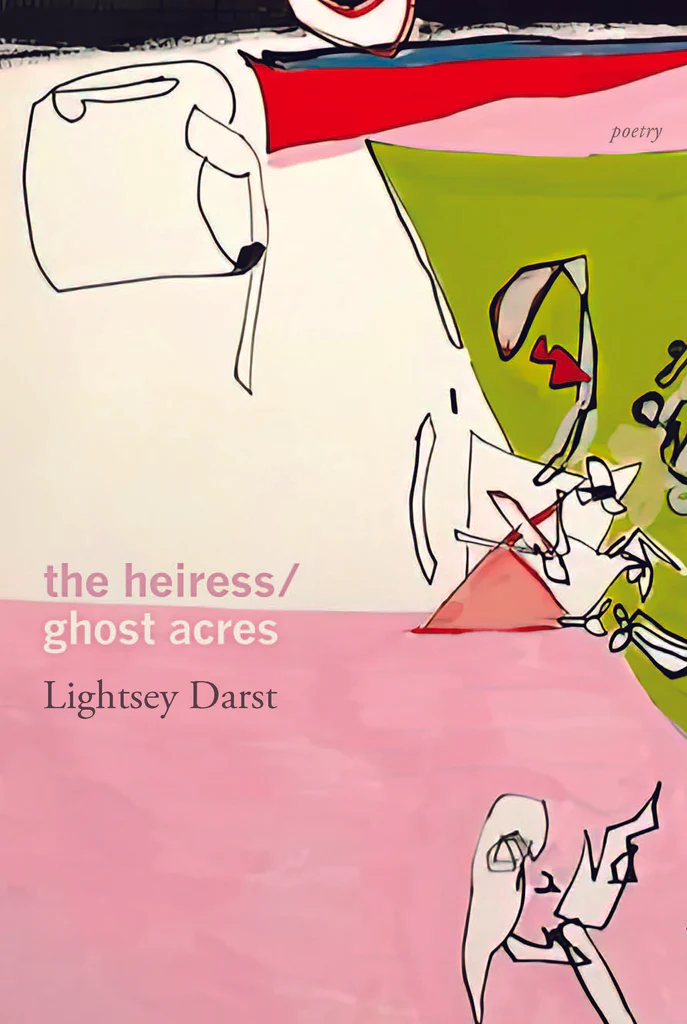

Reprinted from The Heiress / Ghost Acres (Coffee House Press, 2023) with the permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

On “Svalbard”

This poem, “Svalbard,” is named for the seed vault locked away in the Arctic ice, a genetic archive stored up against whatever we might do or whatever might be the consequences of what we’ve already done. This is not an accurate description of one’s children—they live in the consequences of what we’ve done, or even are

the consequences of what we’ve done—yet it’s the parental dream, I think, that through our children all that we love will live and bloom again. The self I was when I wrote this poem both knows and cannot know this. The imperative that children create is not justified by eternity, nor by reference to any outcome. It’s not the outcome but the motion that justifies love, which is a sort of magical thinking—by which I don’t mean false: magical does not mean false—which is why it takes place in a poem. . .

“Svalbard” moves on sound more than I usually allow. Sound and image are forms of beauty in writing, modes of seduction, at times lures of misdirection. If you’re a musical writer, you have to ask yourself about the sources of the music. Why does this pair of words chime? What is singing through me? I’ve been reading an old rhyming dictionary lately, and it is astonishing to see how racist, sexist, and colonialist a mere list of rhyming words manages to be. So music doesn’t justify anything in itself. Here my hope is that the letting go into aural beauty is like letting go into love, a way to move beyond what we know.

I reread Robert Duncan’s “My Mother Would Be a Falconress” recently, and it’s interesting to me that I’ve set up a similar situation—the bird-of-prey child followed by the earth-bound mother—with an opposite conclusion: for Duncan, his thwarted desire to go beyond his mother’s bounds; in my poem, that the mother must go where she can’t. Had I been in a more reflective period of life when I wrote this, and not literally doing the actions described in the poem, maybe I could have noted this similarity and done more with it. That’s the thing about looking back at a finished poem: in the course of finishing it, if you really finished it, you moved yourself on to another place.